Angels. Demons. Humans caught in the middle. Heroes trying to resist temptation and defeat Satan’s emissaries. Sounds a lot like an adventure yarn from the mind of Frank Peretti. But Francis Lawrence’s action-horror flick Constantine, which opens nationwide Friday, is a far cry from This Present Darkness. While the hero is an exorcist casting out demons right and left, he’s not exactly driven by humility or selflessness. And he’s not too fond of God.

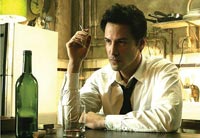

Keanu Reeves (of Matrix fame) plays John Constantine, a chain-smoking exorcist who knows he’s going to hell after his lung cancer does him in. He spends his days trying to earn his way into God’s graces by investing in his favorite side of the cosmic battle between good and evil. That’s the premise. The film chokes on some murky theology and crooked logic, and it delivers more than its fair share of gratuitous violence and gore. (Look for our full review on Friday.)

Christianity Today Movies recently traveled to L.A., where we caught up with Lawrence, Reeves and others involved with the film. We asked questions about the film’s portrayal—and their personal ideas of—good, evil, the afterlife, and redemption. Lawrence and Reeves joined screenwriters Kevin Brodbin and Frank Cappello, and supporting actors Rachel Weisz, Djimon Hounsou, Shia LaBeouf, and Gavin Rossdale for a number of questions from religious press journalists.

Interestingly, Reeves was particularly reluctant to address any questions about his thoughts on religion or spirituality. When one reporter inquired about his religious beliefs, Reeves responded, “Please don’t. It’s something that’s very personal, that’s very private.”

Some highlights from the interviews (note: some of the discussion includes mild plot spoilers):

Does this kind of movie scare you?

Rachel Weisz: I don’t like it actually. It’s not scary to make the movie, but it’s scary to watch it. It’s not a feeling I enjoy. [This one’s] right on the edge of what I can handle.

Djimon Hounsou: I don’t really like watching movies of this nature. The fact that we did it meant I had to watch it. But otherwise, I wouldn’t go. I don’t have the nerves for it. I just can’t deal with it.

What do you hope viewers will take away from seeing Constantine?

Francis Lawrence: I hope viewers get the simple story—the hero’s journey. You have this guy who’s dying of cancer and he knows he’s going to hell. He’s trying to prevent it. He’s a selfish guy, doing things for selfish reasons. And then, he has that turn. It’s a movie about redemption.

Down underneath that, there are [other] ideas that we play with—like the perception of good and evil. What is good? What is evil? It’s not just what we’re told is good and evil. We have to think about that for ourselves.

Shia LaBeouf: I don’t think this movie was made to push ideas or philosophies on anybody. It’s a fun ride. It’s purely for enjoyment purposes only. I think if somebody walks into it with a serious mindset, it could permanently affect them and give them nightmares, or put them in a place they don’t want to be.

I understand that it’s dealing with religious philosophies, and there’s probably a lesson in the film. But I don’t necessarily think anybody’s walking away from the film going, “Now I’m going to change my life because of that.” It’s not The Passion of the Christ.

Weisz: It’s about the capacity that we as human beings have to do good or to do evil. Good and evil occur on the earth, and we have free will. We can choose. But there is also a question of predestination—God’s will. There’s a tension between these two things, and it’s in a state of flux. It’s one of the biggest questions you can ask. For me it’s a question that is unanswerable. We can’t say to what degree we’re in charge. We don’t know these things. It’s a mystery.

Gavin Rossdale: This movie shows us the power of change. It’s so poignant, so resonant. Constantine shows us this man’s journey, what he learns about himself, and the satisfaction that comes from giving yourself away. It gave me the shivers when I watched it. I’m so proud to be part of this film because it has a positive message.

Frank Cappello: The idea of redemption came about [partly] due to casting Keanu. Keanu’s a very spiritual person in his own right. He basically believes that we all have a purpose here.

Keanu Reeves: I think of it as just a kind of secular religiosity. The piece itself is using icons and a platform of a kind Catholic heaven and hell, God and the devil, human souls, fighting for those. But I was hoping that these concepts could become a platform that [is] humanistic, that the journey of this particular hero is hopefully relatable to [viewers]. It’s still a man trying to figure it out.

I think those kinds of journeys—the hero’s journey or with Siddartha—are all kind of seeking aspects [that] have some kind of value to our lives. They offer up [questions like] “Where have you come from?” “What are you fighting for?” “What is striving against you?” [They’re about] coming into a kind of grace—into a kind of light. I think they’re worthwhile.

Do you think good and evil exist in a balance, or is one of them stronger?

Hounsou: I don’t think evil is stronger, or I don’t think any of us would be here! What is the balance? I don’t know. I don’t know that I have the ability to see that. So that’s one subject I’ll leave alone.

Lawrence: I believe the world exists in a polarized way. For there to be good, there has to be evil. There are people around us who have these kinds of energies about them. I think there are two equal forces—there is a balance, and when it shifts one way or the other, something changes. You need one to have the other.

Rossdale: Ultimately, I believe in good over evil.

Whatever the balance—why is it that this movie shows us so much hell, and so little heaven?

Cappello: That’s the point of this story—that it has changed, the balance is shifting, something is going wrong. [Good and evil] are supposed to be equal, they’re supposed to be balanced. So then why are we seeing demons? The balance is upset. Constantine helps balance it out.

The reason heaven isn’t shown as much in these kinds of movies, honestly, is that no one knows how to depict it in a cool way. It seems like an audience loves hell—they want to see demonic images—but if you show them angelic, if you show them light, they go, “Oh gosh.” It is hard to get away from that classic image of light, angels, that sort of thing. So it is a practicality. You’re trying to do something cool, and what does the audience want to see?

Lawrence: [Heaven] is definitely part of John Constantine’s world. It just wasn’t as much a part of this story, because he had to do the fighting.

From his ultimatums to demons, John Constantine clearly understands that one must ask for God’s forgiveness to be forgiven for sins. Why does he insist on working his way into heaven? Why doesn’t he repent and ask God for forgiveness?

Cappello: He wouldn’t. That’s the thing about his character—his pride gets in the way of him asking to be let off the hook. He basically says, “I’m going to do it myself. I believe in myself.” When you believe in yourself, you’re not going to ask for help. You don’t want to lower yourself to beg.

When you walk that line with John Constantine, knowing there’s a heaven, knowing there’s a hell—there’s no faith there! He knows it. He’s not going by blind faith. He’s been there. He’s seen it. What we all wish we knew. Some people accept it totally, some people say, “Prove it to me. I have to see it.” John’s seen it.

Reeves: I think the aspect of repentance is born and expressed in his act—I don’t want to give it away—in what he asks from Lucifer. That’s his repentance—and his sacrifice, and what goes on there—and I think that’s what gives him a shot at going Upstairs. But there’s also the Constantinian twist of, “Did he make the sacrifice so that he could go to heaven, or does he really mean it?” But ultimately he does. Otherwise the Man Upstairs knows—just like Santa Claus—if you’re telling a lie or if you’re really nice. He knows.

What was it like, working on a movie set, surrounded by the symbols and the language of this religious tradition?

LaBeouf:I remember when we were learning how to exorcise people. The priest was very serious about it. He says, “You place your hands there.” And I said, “Well, this is just a movie.” And he said, “No. This is where you place your hands. This is what you hold. This is what you say.” And you’re learning Latin. The priest is so serious, it wobbles you a little bit. You think, “He’s really taking this seriously. There’s a reason. He can’t just be some crazy. They’re bringing him in on this film to help us, to guide us in the religion. He has expertise on this, he’s gone to a university, so he can’t just be some nut job!” So you take that into account. And if he’s teaching you how to exorcise people, then that means it happens!

Hounsou: I think this is one of very few projects you’d ever want to be involved in where you don’t really research. This is one subject you don’t want to do much research on. It’s only given to very few people to have the ability to take those things in. I strongly feel there are certainly things that are not for everyone to hear or see.

For example, Jesus Christ is one of those people that has that unique ability to see—they can read you, inside out, like a book. They know your story even before you discover where you’re headed. That makes Jesus Christ a very special being, a very gifted being. I think [the character of] John Constantine is kind of like that. We talk about [these people] as if we are equal to them, but we are not necessarily given to be receptive to certain things.

Lawrence: It’s a fascinating world. That’s part of what draws some people to films like this—that fascination. A lot of people have an interest until that moment when it might be too close to them, and then they say, “No, I don’t want to know anything.” There was a little of that on the set. People wanted to be very cautious and respectful.

What relevance does this story—the conflict good versus evil, God versus the devil, and the possibility of redemption—have for you in your daily life? Is it a real thing? Or is this all just comic-book fantasy to you?

Hounsou: One connection it has for me: Africa, and certainly my country [of Benin], is a source of voodoo. Growing up there, I heard firsthand some stories. The relevance it has in real life for me has to do with the way I carry myself and the way I treat people and interact with people. If heaven and hell exist, it may be just a condition of our minds. I truly believe those two worlds do exist. If they don’t exist in the sense of God or the devil, they exist in the sense that what you do and how you carry yourself in this life experience leads you to a better life in the afterlife.

Lawrence: I don’t think these things do exist, I don’t think they don’t exist. I’m the person who doesn’t know, and who’s open to all ideas. I was raised by parents who were both lapsed Catholics. My mom was raised Catholic and fell out of it, and my dad was raised Episcopalian and fell out. So I have this weird mix of having Catholicism in my life and real science and logic in my life. I’m somewhere in between. Maybe some of that came through [in the film].

Rossdale: I consider myself a very religious person, but on a much more personal level than the structured religion of necessarily following a particular denomination. I feel very close to a higher power, which I’m used to calling “God,” but I wouldn’t force that on someone else. I would just hope that they have some idea that [serves as] a conscience. I think that kind of struggle goes through people every day—this idea of temptation, the idea of selfish versus selfless.

I firmly believe that you can’t just explain things away on society. There’s a real sense of evil that is the only explanation for atrocious acts that happen to innocent people on a daily basis. It’s very sad.

Reeves: “Spirituality” is a word that I really don’t feel is something to apply to Constantine. If is, it’s very humanistic—as it always is, obviously. It’s more “flesh and blood” than spiritual. These characters seem alienated from their families, from each other, and John is clearly alienated from God. Do you think that is meant to mirror some alienation manifest in our own society?

Weisz: The breakdown of the relationship between man and God, and the breakdown of nuclear families—society is moving more and more toward very alienated individuals. Individuals are on computers all day, and they’re not interacting with other human beings, not being part of a church, not being part of a community. People are alone and alienated.

So yes, I think the movie is holding up a light to something that’s happening in the world, even though it’s a completely supernatural kind of story. But it is the world, isn’t it? It’s a world with supernatural edges that take over. I would say [the movie’s] a comment on that.

For an expanded version of this interview, visit Looking Closer.

Copyright © 2005 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.