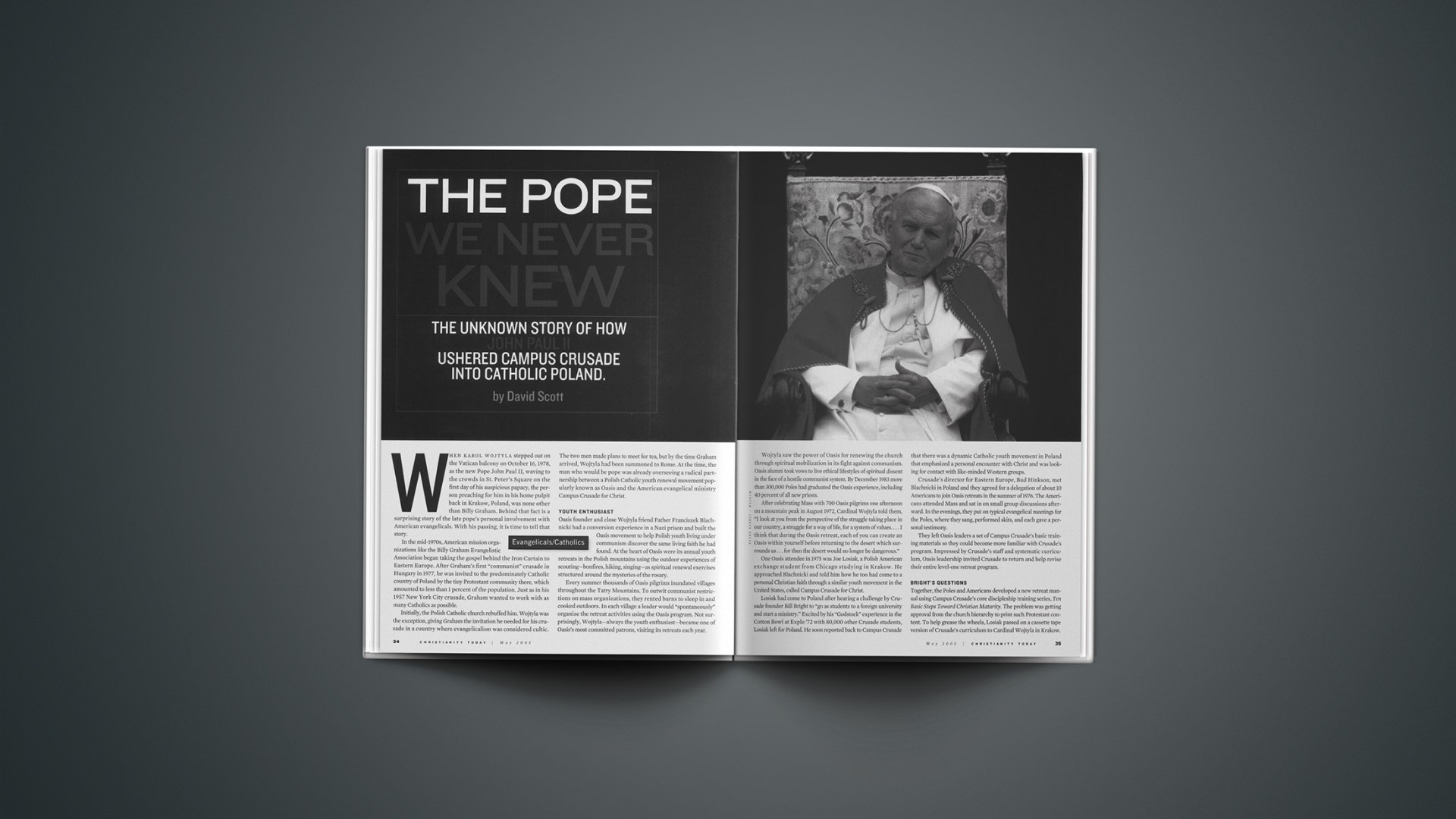

When Karol Wojtyla stepped out on the Vatican balcony on October 16, 1978, as the new Pope John Paul II, waving to the crowds in St. Peter’s Square on the first day of his auspicious papacy, the person preaching for him in his home pulpit back in Krakow, Poland, was none other than Billy Graham. Behind that fact is a surprising story of the late pope’s personal involvement with American evangelicals. With his passing, it is time to tell that story.

In the mid-1970s, American mission organizations like the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association began taking the gospel behind the Iron Curtain to Eastern Europe. After Graham’s first “communist” crusade in Hungary in 1977, he was invited to the predominately Catholic country of Poland by the tiny Protestant community there, which amounted to less than 1 percent of the population. Just as in his 1957 New York City crusade, Graham wanted to work with as many Catholics as possible.

Initially, the Polish Catholic church rebuffed him. Wojtyla was the exception, giving Graham the invitation he needed for his crusade in a country where evangelicalism was considered cultic. The two men made plans to meet for tea, but by the time Graham arrived, Wojtyla had been summoned to Rome. At the time, the man who would be pope was already overseeing a radical partnership between a Polish Catholic youth renewal movement popularly known as Oasis and the American evangelical ministry Campus Crusade for Christ.

Youth Enthusiast

Oasis founder and close Wojtyla friend Father Franciszek Blachnicki had a conversion experience in a Nazi prison and built the Oasis movement to help Polish youth living under communism discover the same living faith he had found. At the heart of Oasis were its annual youth retreats in the Polish mountains using the outdoor experiences of scouting—bonfires, hiking, singing—as spiritual renewal exercises structured around the mysteries of the rosary.

Every summer thousands of Oasis pilgrims inundated villages throughout the Tatry Mountains. To outwit communist restrictions on mass organizations, they rented barns to sleep in and cooked outdoors. In each village a leader would “spontaneously” organize the retreat activities using the Oasis program. Not surprisingly, Wojtyla—always the youth enthusiast—became one of Oasis’s most committed patrons, visiting its retreats each year.

Wojtyla saw the power of Oasis for renewing the church through spiritual mobilization in its fight against communism. Oasis alumni took vows to live ethical lifestyles of spiritual dissent in the face of a hostile communist system. By December 1983 more than 300,000 Poles had graduated the Oasis experience, including 40 percent of all new priests.

After celebrating Mass with 700 Oasis pilgrims one afternoon on a mountain peak in August 1972, Cardinal Wojtyla told them, “I look at you from the perspective of the struggle taking place in our country, a struggle for a way of life, for a system of values. … I think that during the Oasis retreat, each of you can create an Oasis within yourself before returning to the desert which surrounds us … for then the desert would no longer be dangerous.”

One Oasis attendee in 1975 was Joe Losiak, a Polish American exchange student from Chicago studying in Krakow. He approached Blachnicki and told him how he too had come to a personal Christian faith through a similar youth movement in the United States, called Campus Crusade for Christ.

Losiak had come to Poland after hearing a challenge by Crusade founder Bill Bright to “go as students to a foreign university and start a ministry.” Excited by his “Godstock” experience in the Cotton Bowl at Explo ’72 with 80,000 other Crusade students, Losiak left for Poland. He soon reported back to Campus Crusade that there was a dynamic Catholic youth movement in Poland that emphasized a personal encounter with Christ and was looking for contact with like-minded Western groups.

Crusade’s director for Eastern Europe, Bud Hinkson, met Blachnicki in Poland and they agreed for a delegation of about 10 Americans to join Oasis retreats in the summer of 1976. The Americans attended Mass and sat in on small group discussions afterward. In the evenings, they put on typical evangelical meetings for the Poles, where they sang, performed skits, and each gave a personal testimony.

They left Oasis leaders a set of Campus Crusade’s basic training materials so they could become more familiar with Crusade’s program. Impressed by Crusade’s staff and systematic curriculum, Oasis leadership invited Crusade to return and help revise their entire level-one retreat program.

Bright’s Questions

Together, the Poles and Americans developed a new retreat manual using Campus Crusade’s core discipleship training series, Ten Basic Steps Toward Christian Maturity. The problem was getting approval from the church hierarchy to print such Protestant content. To help grease the wheels, Losiak passed on a cassette tape version of Crusade’s curriculum to Cardinal Wojtyla in Krakow. Subsequently, in 1977, the new hybrid Oasis edition of Ten Basic Steps Toward Christian Maturity was fully approved by the Catholic hierarchy and printed with a run of 25,000 copies.

When 27,000 Oasis pilgrims showed up for their retreats the next summer, what they experienced was a strange unabashed mix of Polish Catholicism—Marian devotion included—and American evangelical revivalism. Campus Crusaders returned with 30 staff and trained student leaders, who Blachnicki now invited to teach the main morning sessions covering standard evangelical topics that included salvation by grace and assurance of salvation.

While some might wonder whether Campus Crusade was theologically naïve, the same could not be imagined of Trinity Evangelical Divinity School professor Norman Geisler, whom Hinkson recruited as guest speaker for the Polish summer retreats. After returning from Poland, Geisler wrote of his trip in The Christian Herald: “What I experienced was a dynamic, joyous, Christian, and evangelistic community of believers who were more eager than most American evangelicals I know to learn and live the Word of God.” Geisler described that summer as the most gratifying experience of his then 25-year ministry.

In January 1978 Blachnicki came to America to visit Bill Bright at Campus Crusade’s headquarters in Arrowhead Springs, California. Bright probed Blachnicki about the usual evangelical concerns: “I asked him,” Bright remembered, “What about the Virgin Mary? What about praying to the saints? … He gave me answers which for one with my background were satisfying and amazing.”

Except for a “few fine points,” Bright concluded, “there was basically no difference between what he believed and what I believed.” Little more than a decade later, in 1994, Bright was one of the signers of Evangelicals and Catholics Together (ECT)—a statement of shared convictions by 40 Protestant and Catholic leaders. Bright attributed his support to his personal confidence in the spiritual authenticity of Catholic reformers like Wojtyla and Blachnicki, a trust that was established through their history of working together.

Just like the signatories of ECT would later learn in America, objections to such a relationship were inevitable. The Oasis-Crusade experiment could not survive in Poland without the support of someone in the Catholic hierarchy.

The Oasis movement’s stronghold in the south of Poland flourished under Cardinal Wojtyla’s purview as archbishop of Krakow. According to papal biographer George Weigel, it was he who “extended a mantle of protection over Blachnicki’s work.” When Oasis was restructured using Campus Crusade material, according to the Americans involved, Blachnicki took all of the revised materials to Wojtyla for him to review and pre-approve.

In 1977, an incendiary memo began to circulate among Polish Catholics alleging the partnership was a “Baptist infiltration” of the Church. The Polish episcopate appointed an official commission to investigate. It was stacked, however, with Blachnicki supporters such as Wojtyla. Its report not only repudiated the charges of Protestantization, but also defended and encouraged Oasis’s cooperation with Campus Crusade as a rightful implementation of the calls for ecumenical cooperation in Vatican II and Pope Paul VI’s papal encyclical Evangelii Nuntiandi.

After the commission finished, Cardinal Wojtyla published a statement praising Oasis, and its relationship with Campus Crusade rolled on unabated.

A Most Unlikely Tent Meeting

After Wojtyla became pope, Blachnicki kept him updated on the partnership. Blachnicki traveled to Rome to attend his investiture. Grazyna Sikorska recounts in her book Light and Life: Renewal in Poland (Eerdmans, 1989) how, when the pope was exiting St. Peter’s Basilica, he recognized Blachnicki and shouted to him, “Professor, why don’t you pay me a visit? Please come to supper tonight.”

At dinner in the papal apartment, the pope asked Blachnicki, “What about Oasis? Does this mean that there will be no Oasis for me this summer?” Referring to the papal summer villa, he said, “I know. Come to Castel Gandolfo, put your tents there and have an Oasis retreat.”

As a result, an Oasis retreat—by then based on the hybrid evangelical/Catholic curriculum Wojtyla had approved as cardinal—was held for the Vatican the following summer. Undoubtedly, it was one of the most unlikely evangelically inspired tent meetings ever.

Wojtyla’s papacy benefited from his exposure to American evangelicalism. Through his global travels to reinvigorate the Catholic Church, he became what Weigel described as “the most visible pope in history,” yet he did so in worldwide open-air crusades whose staging is more typical of Billy Graham than the Vatican.

The late pope had seen how mass mobilization centered on a conservative piety could accelerate church renewal. Later he approached the challenges of his papacy with the same mix of traditional spirituality and popular mobilization.

In this respect, John Paul II was not all that different from Bill Hybels or Rick Warren. He tried to harness the forms of popular culture to conservative piety in order to to reinvigorate the church. Ironically, while much of American Catholicism has resisted Wojtyla’s conservatism, many lapsed American Catholics have fueled the growth of evangelical megachurches such as Willow Creek and Saddleback.

Certainly John Paul II’s biggest accomplishment was his ecumenism. The Oasis episode reveals, however, that unlike any other pope before him, John Paul II had the benefit of practical experience, while a bishop, of helping provide pastoral oversight for one of the boldest Catholic/Protestant joint ministry initiatives.

It is not surprising, therefore, that his first encyclical, Redemptor Hominis, acknowledged “the initiatives that have sprung from the new ecumenical orientation,” and noted “the representatives of other Christian churches and communities” that have “committed themselves together with us, for which we are heartily grateful to them.”

Ecumenism, however, is an equivocal affair, its dynamics changing with different contexts and audiences. Geisler, who praised his experience with Polish Catholics, later opposed ect on theological grounds. Similarly, the pope who as a bishop oversaw American evangelicals working in his diocese in Poland is the same pope who called evangelicals in South America “rapacious wolves” for their evangelism of Catholics.

In Poland, foreign evangelicalism posed no threat to the cultural monopoly held by the Polish Catholic church, so evangelicals’ assistance was gladly accepted in the fight against communism, but in South America, evangelicals were the competition.

The pope who in his 1995 encyclical Ut Unum Sint invited input from non-Catholic Christians on the primacy of the office of Peter, is the same man whose Vatican Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in 1999 declared the primacy of Peter “immutable.”

It is a paradox that the conservative piety that gave John Paul II and evangelicals a common cause is the same conservatism that led each to reject the other’s authority claims.

An Evangelical Pope?

What kind of pope gets together with evangelicals? In the face of communism and later Western secularism, John Paul II found common ground with evangelicals in a shared faith in the gospel of Jesus Christ. For many evangelicals it was mutual. After one American missionary heard him speak in Africa, she said, “It was the clearest presentation of the gospel that I ever heard.”

Was Pope John Paul II an evangelical? In the technical historical meaning of the word, of course not. But many American evangelicals saw in Wojtyla a man devoted to a biblical faith in Christ and committed to proclaiming the gospel to an increasingly lost secular world. He shared the core values of American evangelicalism: Christocentrism, Biblicism, evangelism, and anti-secularism. Ironically, Bill Bright and others found more in common with Wojtyla than with their liberal brothers and sisters. For them, the sense of shared faith and common gospel mission made Wojtyla evangelical enough.

With the declaration of martial law in 1981, Blachnicki was exiled. With him and Wojtyla out of the picture, the relationship between Campus Crusade and Oasis broke down on the local level from the lack of leadership necessary to surmount its inherent tensions.

When Blachnicki died in 1987 in Germany, his close friend Larry Thompson, a Baptist from Mississippi, represented Campus Crusade at his funeral. Pope John Paul II sent a message expressing his sorrow at the passing of “a devoted apostle of conversion and spiritual renewal.” The pope also wrote, “It was because of his inspiration that a specific form of ‘Oasis life’ was born in the Polish land.” Although there were many aspects of “Oasis life” to which the pope could be referring, certainly what this pope experienced first-hand was an oasis of evangelicals and Catholics together, if ever there was one.

David Scott is a historian, writer, and speaker with the ministry www.lifetwozero.org. He worked with Campus Crusade in Poland in 1988.

Copyright © 2005 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

More recent coverage of the John Paul II’s death include:

Pope’s Funeral Spotlights Kinship Between Catholics and Evangelicals | Once antagonistic communities are now on the same side of several cultural issues. (March 08, 2005)

Christian History Corner: Signs of the Reformation’s Success? | Reformation scholar Timothy George discusses Pope John Paul II’s historical significance and this ‘momentous’ era of Catholic-evangelical dialogue. (March 08, 2005)

Pope Gave Evangelicals the Moral Impetus We Didn’t Have | Timothy George discusses how “the greatest pope since the Reformation” changed evangelicalism without us knowing. (April 06, 2005)

Pope ‘Broadened the Way’ for Evangelicals and Catholics | Theologian Tom Oden sees continued cooperation ahead. (April 05, 2005)

Pope Saw His Final Pain as Public Suffering | John Paul II embodied the “culture of life.” (April 05, 2005)

How the Pope Turned Me Into An Evangelical | A Christianity Today associate editor recalls growing up Catholic in John Paul II’s Poland. (April 04, 2005)

Pope John Paul II and Evangelicals | Protestants admired his lifelong admonition to “Be not afraid! Open the doors to Christ!” An interview with George Weigel. (April 04, 2005)

He Was my Pope, Too | Now that John Paul II is gone, I am even more of an orphan than the Christians in the Roman church. (April 04, 2005)

Protestants Laud Pope for Ecumenical, Social Stands | He was ‘unquestionably the most influential voice for morality and peace in the world during the last 100 years,’ says Billy Graham. (April 04, 2005)

Pope John Paul II, Leader of World’s 1 Billion Roman Catholics, Is Dead at 84 | Third-longest papacy marked by a passion to evangelize the whole world. (April 04, 2005)