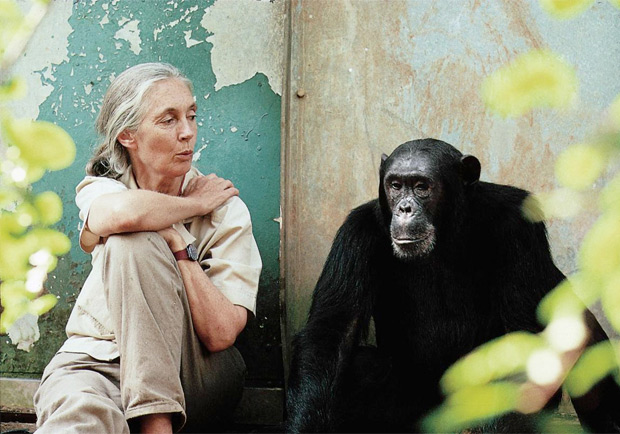

As the new Disneynature film Chimpanzee opens today (our review), we had the opportunity to chat with Jane Goodall, the world’s foremost expert on chimps. In an interview with CT film critic Steven Greydanus, Goodall talked about the film, the behavior of a species she has observed for decades, and a possible “spiritual side” to our primate friends. A portion of the film’s opening-week box office proceeds will be donated to the Jane Goodall Institute.

What did you think of the film?

It’s wonderful—really mindblowing.

How does it compare to other chimpanzee documentaries you’ve seen?

Well, it just puts them all in the shade. It’s absolutely brilliant. It’s a mixture of unbelievably good cinematography, fantastic behavior of the chimpanzees, the incredible feeling the filmmakers have got for what it’s like to be deep in the forest, the spectacular views of the whole area from above. And then on top of all that, you’ve got this extraordinary story unfolding within the chimpanzee community—a behavior which is almost unheard of. It’s an incredible film.

What misconceptions about chimps do you think people still have? Will this film help to correct any of them?

I think it will give people a real feeling for what it’s like for chimpanzees out in the wild, and that will be new for most people. They’ll come away totally in love with the infant [an adorable little one named “Oscar”] who’s the star of the film, and moved by the tender side that emerges in the great big dominant alpha male. That’s charming. They’ll realize that underneath the tough exterior of a male chimp can be a tenderness which we’ve recorded on a number of occasions.

Although they’ll fall in love with Oscar, people should also realize that he’ll grow up to be like the leader of, quote, the “enemy” chimp community, and they won’t think any longer about buying a baby chimp as a pet. At least I hope. And they’ll realize that baby chimps belong in their communities, and how cruel it would be to take them away from their mothers.

People will also see how like us chimpanzees are, how they share many of our emotions, and the way they think. The way the young ones learn.

Some people felt the movie pressed the anthropomorphic angle too much—for example, the way it presented the two rival chimp groups almost as movie heroes and villains.

Yes, a lot of people have talked about that. And of course we don’t know what is going on in the chimpanzee mind. People who know nothing about the chimpanzees might have been very confused if there weren’t some commentary to help them understand, more or less in human terms, what was going on.

Maybe in places the commentary could have been toned down a little bit. But this is a film geared to the general public, including young people.On balance, I think [the narration] is okay, and some of it’s quite funny. I think people who really understand [chimpanzees] will perhaps tolerate it, knowing that so many people wouldn’t understand at all without the narration. On balance, I’m not unhappy.

In your study of chimpanzees, what has impressed you concerning their non-humanness—the ways in which they’re unlike us?

The main difference, I feel, is the explosive development of the human intellect, which I suspect has been triggered in large part by the fact that we came up with this ability to communicate in the way that you and I are doing right now, with words. So for the first time a species is able to communicate about something which isn’t present, make plans for the distant future, and discuss an idea. Chimpanzees cognitively can use human-like language; they have the ability to have developed a language like this, but as far as we know they haven’t.

What are other aspects of human uniqueness, besides than our intelligence?

Tied in with intelligence, we’ve developed and been able to elaborate on cultural acquisition of behavior. Chimps definitely have their own kind of primitive culture, but we live by our culture, we talk about it, children are taught how to model behavior. Our whole lives are bound by our culture, really. So even though we’re reaching out to understand other cultures, nevertheless it’s our language that’s enabling us to do that.

What makes us special? People say maybe we have a soul and chimpanzees don’t. I feel that it’s quite possible that if we have souls, chimpanzees have souls as well.

Other people say, “What about religious behavior? Do chimps show any signs of that? In Gombe [Tanzania’s Gombe Stream National Park, where Goodall did much of her research], there are fantastic waterfalls where the water drops eighty feet through a natural gorge. There’s a wind caused by the displacement of air with the dropping water, and ferns waving and vines hanging down. And this spectacle causes what we call an incredible “waterfall dance.” The chimpanzees will sway rhythmically from foot to foot, and sometimes sit and look at the waterfall.

That makes me feel that if the chimpanzees could speak, if they could share the behavior that makes them perform these displays, which I think must be related to awe and wonder, that could lead to one of those early animistic religions where people worship water and sun and elements they can’t understand.

Do you think that in doing so, chimpanzees—and humans in their religious behavior—apprehend something real?

Well, that’s what different people think different things about, isn’t it? From my perspective, I absolutely believe in a greater spiritual power, far greater than I am, from which I have derived strength in moments of sadness or fear. That’s what I believe, and it was very, very strong in the forest. What it means for chimpanzees, I simply wouldn’t say. Since they haven’t had the language to discuss it, it’s trapped within each one of them.

Goodall images by Stuart Clarke and Michael Neugebauer.

Copyright © 2012 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.