1. It's for sale.

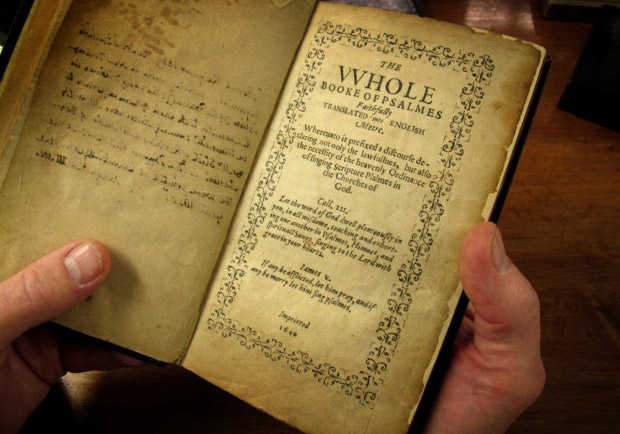

The main thing you need to know right now about the Bay Psalm Book is that a copy of it is up for public sale for the first time since 1947.

Last week, Boston's Old South Church voted 271-34 to sell one of its two remaining copies of the 1640 Bay Psalm Book—one of the most historic volumes in American religious history. When it goes up for auction, Sotheby's vice chairman David Redden told The Boston Globe, it's likely to fetch between $10 million and $20 million. (The historic and liberal United Church of Christ congregation is also selling 19 pieces of early American communion silver.)

The church says its building needs at least $7 million in repairs, and its endowment needs to grow to support at least $300,000 in annual repairs after that. "We will take this wonderful old hymn book, from which our ancestors literally sang their praises to God, and convert it into doing God's ministry in the world today," Nancy Taylor, the church's senior minister, said in a press release.

The sale was not without controversy. Church historian Jeff Makholm disputed Taylor's characterization of the sale. "We're not helping the people in the community by air conditioning offices," he told WBUR. "It is right for the members to question whether that has anything necessarily to do with the mission of the church. But these books do have something to do with the mission of the church."

2. It's widely regarded as the first book published in America.

In 1638, a mere 18 years after the pilgrims landed at Plymouth, the John set sail for the Massachusetts Bay Colony with Joseph Glover, his wife Elizabeth, their five children, and his wood and iron printing press. Glover died at sea, and it fell to his wife (overseeing locksmith Stephen Daye) to set up the press in the Glovers' Cambridge home. While the press had many purposes, the British colonists were particularly eager to see it be used to print their first book: a new translation of the Psalms from Hebrew, put into metrical rhyme for congregational singing. "Thirty pious and learned ministers" throughout New England worked on the translations, including noted Puritan leaders Richard Mather and John Cotton.

About 1,700 copies of the first edition were printed. Of these, only 11 remain. And of those, only five are complete copies.

For a long time, it was also the most valuable book in America. The last time one was up for public sale, in January 1947, it went for $151,000 (that's about $1.6 million in 2012 dollars) and broke all records for book auction sales—nearly doubling the price for a First Folio of Shakespeare (though one of these recently sold for $5 million).

3. It's not really the first book published in the New World.

Everyone acknowledges that the Bay Psalm Book wasn't the first item to come off of the Glover-Daye press. As Massachusetts Bay Colony Governor John Winthrop recorded in his journal, "The first thing which was printed was the freemen's Oath; the next was an almanac made for New England by Mr. William Pierce, mariner; the next was the Psalms newly turned into metre."

But the Spanish beat the English by more than a century. Breve y Mas Compendiosa Doctrina Christiana en Lengua Mexicana y Castellana ("The Brief and Most Concise Christian Doctrine in the Mexican Language"), a catechism by Mexico City archbishop Juan de Zumarraga, came off of Juan Pablos's presses in 1539. Hundreds of books were published between it and the Bay Psalm Book.

Fine, then. It was the first book written and published in what is now the United States. And if the Library of Congress wants to call it "America's First Book," we won't argue.

4. It was the result of several "worship wars" in Europe and the British colonies.

A few years before Pablos's presses began cranking out Catholic doctrine in Mexico, Martin Luther's psalm-hymns began rolling off presses in Germany. While Luther is better known for his more theological hymns like "A Mighty Fortress," he composed eight metrical hymns like those found in the Bay Psalm Book.

"[Our] plan is to follow the example of the prophets and the ancient fathers of the church, and to compose psalms for the people [in the] vernacular, that is spiritual songs, so that the Word of God may be among the people also in the form of music," he wrote in 1523.

Calvin was even more enthusiastic about metrical psalms, and, unlike Luther, thought them vastly superior to hymns.

"Wherefore, when we have sought on every side, searching here and there, we shall find no songs better and more suitable for our purpose than the Psalms of David, dictated to him and made for him by the Holy Spirit. But singing them ourselves we feel as certain that God put the words into our mouths as if He Himself were singing within us to exalt His glory."

Luther and Calvin agreed, however, that singing was for everyone. In the medieval church, singing had almost exclusively been for clergy and choirs. The Reformers' emphasis on congregational singing was driven by theology. But as Zoltán Haraszti, longtime keeper of rare books at the Boston Public Library, wrote in The Enigma of the Bay Psalm Book, it had a pragmatic function as well.

"Communal singing especially engendered a feeling of unity," he wrote. "Thus psalm singing, produced by the Reformation, in turn one of its most powerful weapons. In spreading and deepening the new religious movement, it accomplished more than all the treatises of the theologians."

In 1562, all 150 Psalms had been translated into English, set to rhyme and meter, and published with the Church of England's Book of Common Prayer. It helped to build unity, but it also divided.

As it turns out, the Puritans didn't like it much, either in Old England or in New. "We have cause to bless God in many respects for the religious endeavors of the translators of the psalms into meter usually annexed to our Bibles," the preface to the Bay Psalm Book reads. "Yet it is not unknown to the godly learned that they have rather presented a paraphrase than the words of David."

Wanting to "enjoy this ordinance in its native purity," the preface announces, "we have therefore done our endeavor to make a plain and familiar translation of the psalms and words of David into English metre, and have not so much as presumed to paraphrase to give the sense of his meaning in other words."

5. It lost the first major American worship wars.

The Bay Psalm Book was an instant success, used in almost every church in New England, as well as many churches in other colonies. Its first printing of 1,700 is particularly notable when one historian notes that 50 would have placed two in every Massachusetts Bay Colony church. And it went through at least another 26 printings.

But by the early 1700s, it was already a point of contention. Its creators anticipated this. The preface begins: "The singing of Psalms, though it breathe forth nothing but holy harmony, and melody: yet such is the subtlety of the enemy, and enmity of our nature against the Lord, and his ways, that our hearts can find matter of discord in this harmony, and crotchets of division in this holy melody."

But as at least one Englishman complained, metrical Psalms could be really boring. Said one, prefacing his own metrical Psalter:

Tho' the Psalms of David are a Work of admirable and divine Composure … when the best of Christians attempt to sing many of them in our common Translations, that Spirit of Devotion vanishes and is lost, the Psalm dies upon their Lips, and they feel scarce any thing of the holy Pleasure.

The writer was Isaac Watts, who by then had already begun his life work of creating 750 or so hymns that weren't simply psalm translations—and that contained much more New Testament themes and doctrine. (He largely kept the music the same, using the older psalm meters.)

In 1739, George Whitefield traveled from England to America for his preaching tour. He brought with him Watts's hymns, and American worship changed almost instantly. By 1742 Jonathan Edwards's church had added hymns to its worship. In fact, he said, the church had had introduced hymns "in my absence on a journey and seemed to be greatly pleased with it and sang nothing else, and neglected the Psalms wholly." Seeing "in the people a very general inclination to it" but being "far from thinking that the Book of Psalms should be thrown by in our public worship," he instituted a kind of blended worship service, adding Watts's hymns in with the traditional metrical psalms.

Edwards's was far from the only church to try blended worship. The Puritan church in Spencer, Massachusetts, had initially used the Bay Psalm Book, but switched to a more contemporary version called New Version of the Psalms. In 1761, apparently divided over worship styles, the congregation voted to try the Bay Psalm Book for a month, then Watts's hymns for a month, then vote on which of the three to use. The Bay Psalm Book won in a 33-14 vote (with 6 for New Version), but disgruntled hymn lovers continued to press their case. The church then decided to use the Bay Psalm Book and the hymnal together in services, but that seems not to have made anyone happy. In October 1769 it took another vote. This time Watts won by a vote of 26-6. And, as would be repeated in countless other churches, hymns entirely supplanted metrical psalms. Eventually even new editions of the Bay Psalm Book itself would include hymns. (The 1758 version includes 50 hymns, 42 of which were by Watts.)

6. It's … um … actually not very good.

There's a reason not one of the Bay Psalm Book's translations is currently sung in American churches. They're universally panned, even as the colonial Puritans have enjoyed resurgent interest in various quarters. Even Haraszti, who had a ringing passion for the book, admitted that "the work is no literary treasure trove." But he said criticism was overblown and undeserved, "especially when, on nearer inspection, the despised passages turn out to be literal transcriptions of the King James Version."

Among the most mocked of the translations is that most famous of psalms:

The Lord to mee a shepheard is,

Want therefore shall not I.

Hee in the folds of tender-grasse,

Doth cause mee downe to lie:To waters calme me gently leads

Restore my soule doth hee:

He doth in paths of righteousness

for his names sake leade mee.

It's also hard to imagine a congregation enthusiastically singing Psalm 137 out of the book:

Blest shall hee bee, that payeth thee,

daughter of Babylon,

who must be waste: that which thou hast

rewarded us upon.O happie hee shall surely bee

that taketh up, that eke

thy little ones against the stones

doth into pieces breake.

The writer of the book's preface admits that some of the versifications are a bit rough.

"If therefore the verses are not always so smooth and elegant as some may desire or expect; let them consider that God's altar needs not our polishing," he wrote. "We have respected rather a plain translation, than to smooth our verses with the sweetness of any paraphrases, and so have attended conscience rather than elegance, fidelity rather than poetry."

But even Cotton Mather admitted that "a little more art was to be employ'd upon it," and the second edition, published in 1647, had significant revisions.

7. This isn't the first time Old South has parted with a copy controversially.

Old South Church is considering selling one of its two copies (it's keeping the better of the two). But of the 11 copies still in existence, Old South used to own five, thanks to Rev. Thomas Prince's efforts in 1703 to create a definitive regional library.

A 1954 article in Life describes how it parted with the other three copies as "a masterpiece of thievery" and "a very proper swindle." It wasn't quite that bad. Around 1850, the church apparently traded two copies away for new bindings on its remaining copies. ("If this is the case, it is perhaps more to be deplored than that duplicates were allowed to leave the … collection," says a 1948 history.)

In 1860, the church traded a third copy for two other books (worth far less even then). Some church leaders unsuccessfully tried to get it back—as did Haraszti on the church's behalf. But to no avail. Eventually, however, the copies made their way to Yale University, the Library of Congress, and the John Carter Brown Library.