(Revised and Updated, 6/21/2013)

"There is a solemn procession to the altar. The choir is chanting. A bishop in a long, black robe and a full, gray beard swings an incense burner back and forth. We bow. We cross ourselves. It's a typical Sunday service at the Evangelical Baptist Church of Georgia.

"Yes. Baptist."

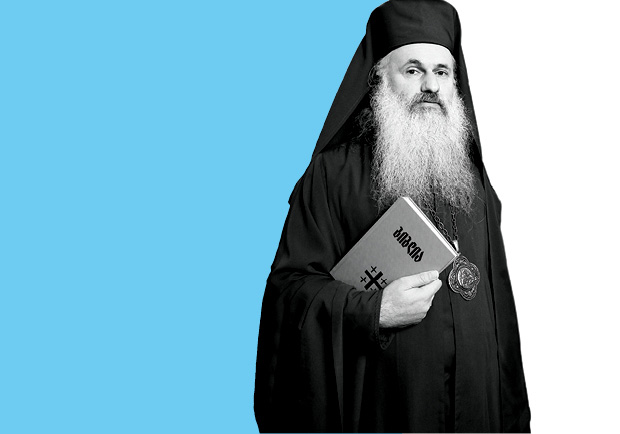

That is how Cuttino Alexander, an American pastor, recently described worship at the Evangelical Baptist Church of Georgia (EBCG), a denomination famous for its unusual method of contextualizing the gospel. The man behind those efforts: Malkhaz Songulashvili, archbishop of the EBCG.

For many citizens, being Georgian means being Orthodox; 82 percent of Georgia's 4.5 million citizens identify as Orthodox. Songulashvili, a Georgia native, says he could have created "a Baptist church for Baptists, or a Baptist church for Georgians." He chose the latter. Call it the seeker-sensitive approach in the former Soviet state.

Songulashvili claims a total community of 17,000, making it the largest Protestant denomination in Georgia. [Editor's note: According to the East-West Church and Ministry Report, statistics from Operation World give 2010 figures of 5,796 Evangelical Christian-Baptist members for Georgia, with a larger number including affiliates of 15,600.] Brian Wolf, a dissenting Georgia missionary with International Gospel Outreach, puts the number much lower, at about 2,000 adult members. Yet its contextual model is powerful. "I know of no other Baptist union or convention in the world that has exegeted its context for ministry as brilliantly and powerfully as [the EBCG]," claims Baptist theologian John Sundquist.

Many Orthodox view Baptists as a Western-inspired and -funded fringe or underground movement, decrying them as sectarian heretics. Baptists, in turn, have regarded Orthodox as unconverted. Yet Songulashvili has "uncovered the treasures" of the Orthodox tradition, he says, and incorporates them into faith and practice. He intends to lead a denomination that's Baptist in theology while both Georgian and Orthodox in culture—and to break the longstanding impasse between evangelical Protestants and Orthodox throughout Eastern Europe.

Structurally, the EBCG calls itself an Episcopal Baptist church. It is headed by an archbishop and three bishops—one of whom is female. Female ordination and liturgical dance both mark EBCG's departure from Orthodoxy.

But the tradition of worshiping God with all five senses is one Orthodox gift that the EBCG receives "with gratitude," says Songulashvili. Consequently, the EBCG has founded a school for icon painting and uses incense in services. It has a monastic order and holds processions and pilgrimages.

Since the Georgian Orthodox Church withdrew from the World Council of Churches in 1997, the EBCG has been the largest denomination in Georgia that remains strongly active in the global ecumenical movement. It's a member of the Geneva-based Conference of European Churches. Consequently, the relatively tiny EBCG has become known throughout Georgia. Konstantine Gabashvili, a chairman of Georgia's parliament, says, "We cannot think of any other church or confession that has been as active in the life of wider society."

Songulashvili was ordained in 1994 and became an archbishop in 2006, and is himself a remarkable example of bridge-building. His 2008 wedding on top of Mount Didgori included 60 foreign guests from 14 countries. More than 600 Eastern Orthodox, Catholics, Anglicans, Armenian Apostolic, Jews, Muslims, atheists, and Baptists—including the general-secretary of the Baptist World Alliance—attended the ceremony and feast of music and dancing.

Peacemaker

The EBCG's work has left Georgian Orthodox leaders both flattered and disappointed, says the archbishop. Flattered that Baptists have become ambassadors of Orthodox spirituality, but disappointed that the Baptists don't join the Orthodox fold. The relationship is one of "critical solidarity," says Songulashvili: "We criticize them for corruption and religious nationalism" and their insistence on preferential treatment by the government.

The EBCG emphasizes freedom of conscience, a core Baptist tenet that shapes the archbishop's mission to Muslims, who make up about 10 percent of Georgia's population. Christians, he says, are to "speak of being Christian without imposing anything. The key word should be friendship. We simply show our love and friendliness to everybody, then leave the rest to God."

Songulashvili says he dreams of a society in which Christians and Muslims help each other build their own places of worship. He has met with leaders of Georgia's Muslim minority and refugees from war-torn Chechnya, a republic in southern Russia (and where the brothers behind the Boston Marathon bombings were originally from). In return, a refugee imam from Chechnya promised, "When I return to Grozny [the capital of Chechnya], I will do two things: I will build a new mosque, because ours was destroyed by the Russians. I will also build a Baptist church, because the Baptists were the only people with us in our time of need."

Songulashvili's outreach to nationalists, hostile to the presence of non-Orthodox in Georgia, is just as striking. Consider the dramatic public trial of radical Orthodox priest Basil Mkalavishvili and his followers, who torched a building that contained 17,000 Bibles owned by Baptists. Songulashvili walked up to the defendants' cage and publicly forgave them. Asked by the defense about desired damages, Songulashvili demanded "nothing except the red wine, which we will drink together when they are set free." The Orthodox ex-priest responded in kind, sending icons and cake to the EBCG headquarters. After Mkalavishvili (now released) was sentenced to six years in prison, the archbishop wrote, "In the past we were praying that [he] be arrested. Now we are praying that he be released."

The Baptist Peace Fellowship, an international group based in North Carolina, is sponsoring Songulashvili on a trip to war-torn Aleppo, Syria, one of the many hotbeds of the Arab Spring. In April, a UN commissioner called the ensuing Syrian civil war the worst humanitarian disaster since the cold war. The fellowship believes the archbishop's peacemaking track record will bear fruit among Christian and Muslim leaders there.

"I have been friends with the local community in Aleppo since 2004," wrote the archbishop recently. "They are devastated by the situation in their city, and they do not know how to handle the crisis. The humanitarian situation is worsening. In order to build capacity for a culture of peace, it is essential that we as Christians show tangible empathy with the suffering Muslims and Christians of Syria in their time of despair."

Another Baptist Split

But not all is well among evangelicals in Georgia. The EBCG's worship and ties to Western evangelical and ecumenical groups have divided it from the Baptist unions of Belarus, Ukraine, Russia, and the Central Asian republics. Even Baptists in Georgia are split: The Evangelical Baptist Association of Georgia, a second Baptist union of 6 pastors, 30 churches, and some 800 adult members, became official last October. The Moscow-based Euro-Asian Federation of Unions of Evangelical Christians-Baptists rushed to make the dissident movement a member—and is still estranged from the EBCG.

The Cooperative Baptist Fellowship (CBF), based in the state of Georgia, has meanwhile publicly supported Songulashvili. Frank Broome, CBF coordinator for Georgia, has noted that the two denominations "share things in common: They are accustomed to being criticized by fellow Baptists for inclusion of women in ministerial leadership, and for working cooperatively with other Christian groups." (The CBF split from the Southern Baptist Convention in 1991 over women's ordination.)

Songulashvili publicly championed the pro-Western revolutions of Georgia, Ukraine, and Belarus, but Baptist leaders in Slavic Eastern Europe and Central Asia refuse to speak out on political issues. When Songulashvili arrived in Belarus in March 2006 without the blessing of the country's Baptist leaders, he spent three days in jail, then was expelled from the country. The archbishop has pushed individual human rights and Western-style elections, and has distanced himself from the Russia-inspired socialist heritage and that power's present-day interests. His thought mirrors the church and political divisions of Europe at large: Like the Georgian government, the EBCG broke with Russian-sponsored Eastern Europe and joined the West. As a result, his relations with the pro-Russian multitudes and with Protestant fundamentalists are fraught with tension.

On the other hand, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kievan Patriarchate gave the archbishop one of its highest awards in April 2011. The young Ukrainian church is at odds with the Russian Orthodox Church Moscow Patriarchate, the world's largest Orthodox denomination. Songulashvili has fought against the Russian yoke, appealing for national sovereignty and vehemently supporting the Georgian position in the war with Russia over South Ossetia and Abkhazia in August 2008. But it is not easy to find common ground with Russian evangelicals, who are often as Russian as the archbishop is Georgian. He concedes these are unresolved weaknesses.

"Our allegiance lies with Eastern spirituality and Eastern culture. It may be true that we do not have as strong of formal political ties with Eastern European churches as we do with others," he says. "This is not intentional. I want to believe the time will come when Georgian Baptists can witness together with the other Baptists of Eastern Europe. But this will not happen until the next generation arrives."

That generation may be arriving soon. In 2010, an American pastor reported that on any given Sunday in Peace Cathedral, where Songulashvili serves, "the sanctuary [is] overflowing, with younger people crowding at the doorways to participate in the services." A bearded, wine-drinking, highly educated Baptist hierarch in flowing robes and sandals is apparently more attractive to Georgian youth than a podium-pounding Eastern European preacher in an ill-fitting suit.

"Our church is growing slowly and steadily," says Songulashvili. "But that growth expresses itself mainly in a deepening of faith and its influence on Georgian society. Our church has stopped being mad about numbers. We think concentration on numerical growth is a reflection of the Western capitalist system."

Songulashvili has been mostly absent from Georgia over the past five years, pursuing doctoral studies at England's Oxford Centre for Mission Studies. But he has completed his doctoral studies, and preached his final sermon in Oxford this March. Return to his homeland is imminent. Georgia would do well to brace itself for some surprises.

William E. Yoder, PhD, is a freelance journalist based in Moscow. He is a volunteer consultant with the Russian Union of Evangelical Christians-Baptists and the Russian Evangelical Alliance.