Editor's note: Dallas Willard died May 8 at age 77, days after being diagnosed with cancer. A shorter version of the following tribute from John Ortberg ran on CT's site that day.

When Dallas Willard was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in late summer 2012, he said, "I think that when I die, it might be some time until I know it."

Dallas was always saying things that no one else would think to. He said that a person is a series of conscious experiences, and that for the one who trusts and follows Jesus, death itself has no power to interrupt this life, for Jesus said that the one who trusts in him will not taste death.

Dallas died on May 8, 2013. I'm not sure if anyone has told him yet. But I know that for the lives touched by his mind and heart, there is a void. A philosopher at the University of Southern California (USC) for nearly five decades, he was the smartest man I have ever known. But it was the quality of his life—the extent to which he lived in the reality of the kingdom—that shaped the people who knew him the best.

Somebody once asked Dallas if he believed in total depravity.

"I believe in sufficient depravity," he responded immediately.

What's that?

"I believe that every human being is sufficiently depraved that when we get to heaven, no one will be able to say, 'I merited this.'"

The doctrine of sufficient depravity is one of a thousand truths from Dallas that seem novel and yet, the more we reflect on them, point to the most fundamental tenets of our faith. Since he died, one of the scenes I've had in my mind is of Dallas arriving at the gates of heaven, only to be turned away with a stamp marked INSUFFICIENT DEPRAVITY. Dallas himself would have insisted he had more than his fair share of depravity. He would have insisted that what we love in a life such as his is the One to whom Dallas constantly and joyfully pointed. What we love most about Dallas is the Jesus in him.

Hey Dallas

Because Dallas wrote extensively on spiritual formation and taught philosophy, one might think he came from abundant education and culture and resources. In fact, he grew up in rural Missouri in poverty. Electricity did not come until he was mostly grown up. His mother died when he was 2 years old; her last words to her husband were, "Keep eternity before the children."

He once read a book by Jack London that described the world from an atheistic point of view. Dallas said that he'd never known books could contain such ideas, and after that encounter his mind was never the same. He was 9 years old.

He became an insatiable reader: "When I left home after graduating high school, I left as a migrant agricultural worker with a Modern Library edition of Plato in my duffel bag. It sounds kind of crazy, but I loved it. I loved the stuff. Before I knew there was a subject called philosophy, I loved it."

He attended Tennessee Temple and did graduate work at Baylor University before receiving his PhD from the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He then taught for 48 years at USC, where for a time he chaired the philosophy department. He is regarded as a leading translator and authority on the German phenomenologist Edmund Husserl. He was, along with scholars like William Alston and Alvin Plantinga, a significant influence in a renaissance of evangelical thinkers within contemporary academic philosophy.

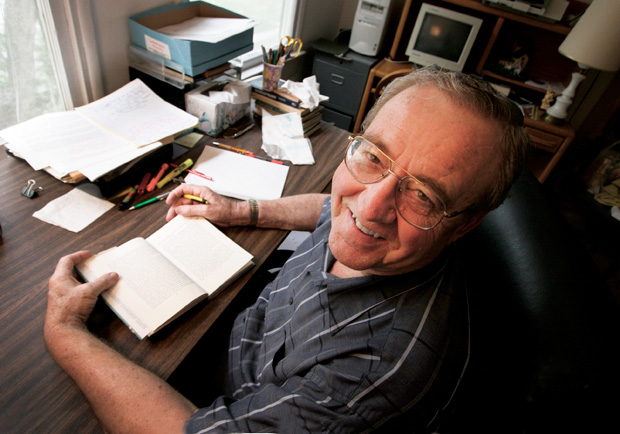

Like his mind, his home was furnished with books. He had a secondary library that occupied a second house, and a tertiary library that filled his office at usc. After his cancer diagnosis, a group of us packed up well over 100 boxes of books that only made it to his quaternary library in a nearby garage. They were in multiple languages and stretched from Homer to Harry Potter.

Dallas touched many believers through his teachings and writings, which are often categorized as "spiritual formation." But Dallas was more centrally preoccupied with the "kingdom of God"—what he called "the with-God life." He said the four great questions humans must answer are: What is reality? What is the good life? Who is a good person? And, how do you become a good person? His concern was to answer those questions, and live the answers. And he was simply convinced that no one has ever answered them as well as Jesus.

For Dallas's students and friends—and these categories largely overlapped—the best moments, the ones I will miss the most, were the moments with no hurry, no schedule constraint, nothing in the world but time and God and love. Then you could ask him, "Hey, Dallas . . ." (There are a thousand stories that begin with the statement, "Someone asked Dallas.")

"Hey Dallas . . ." You could see him thinking—not about the problem, which he had worked out long ago, but about how to express it in a way that those of us listening might be able to grasp it. So that it would not be a "pearl cast among swine"—one of dozens of Scripture passages I heard him explain better than any professional exegete.

Dallas and I used to play a game. I would ask him for definitions of all kinds of words. And every definition would contain a clarity and freshness and precision that would require folks to sit and reflect for a while. "Hey Dallas . . . ," and then I'd ask him about any word or concept that mattered, and would receive a brief education in the possibilities of redeemed thought.

The word spirit. "Disembodied personal power."

Beauty. "Goodness made manifest to the senses."

A disciple is "anyone whose ultimate goal is to live as Jesus would live if he were in their place."

Dignity is "a value that creates irreplaceability." (This one, he graciously attributed to Immanuel Kant.)

Dallas was ruthlessly committed to logic, clarity of thought, and the constant cultivation of reason. He held such commitments because they were indispensible to navigating reality, and because helping people navigate reality is indispensible to love.

"Hey Dallas, what is reality?"

"Reality is what you can count on."

"Hey Dallas, what is pain?""Pain is what you experience when you bump into reality."

Because of this, Dallas had a deep aversion for Christian speakers or writers who use emotion to manipulate a temporary response from their listeners—a response that bypasses their "mental maps" and leaves the audience in worse shape than when they started. He said at one conference that speakers should never tell stories. This prompted a group of publishing types to propose the "Dallas Willard Study Bible," with all the stories taken out. (Pretty much just Leviticus.)

"What is spiritual maturity?"

"The mature disciple is one who effortlessly does what Jesus would do in his or her place."

"What exactly does it mean to glorify God?"

"To glorify God means to think and act in such a way that the goodness, greatness, and beauty of God are constantly obvious to ourselves and all those around us. It means to live in such a way that when people see us they think, Thank God for God, if God would create such a life."

Remarkable Mind

Dallas has impacted the church—evangelicalism and beyond—through the power of historically informed thought that simply makes more sense of existence than the alternatives. He valued the scholarly guild and contributed to it. But he also knew the limits of the guild, and ultimately sought to contribute to moral and spiritual knowledge in a way that transcended current guild norms.

Obviously, Dallas had a remarkable mind—not brain, mind you. He was always careful to note the distinction between mind and brain. "God has never had a brain," he would say, "and has never missed it."

But his life and his heart were better than his mind. My own life was forever changed when I read his book The Spirit of the Disciplines 24 years ago. I contacted Dallas after having read it, and—for no particular reason—he invited me to his Southern California home. I experienced there what countless others have: the unhurried, humble, selfless attention of a human being who lived deeply in the genuine awareness of the reality of the kingdom of God.

Somebody once said of Dallas: "I'd like to live in his time zone." During one of his lectures, a listener challenged him with statements that were both offensive and incorrect. Dallas paused, thanked the person for their comments, and then simply moved on to the next question. Somebody asked Dallas afterward why he had not countered the student's argument and put him in his place. "I'm practicing the discipline of not having to have the last word."

This is part of why Dallas would never debate nonbelievers. Rather, he engaged in mutual conversations where both parties could seek truth together. He would often say, "I'm sure Jesus is the kind of person who would be the first to say you must ruthlessly follow the truth wherever it leads." Through the last week of his life, he was still hoping to help believers engage nonbelievers by looking together at questions where people get stuck in their actual lives rather than by trying to win intellectual arguments.

Like watching Usain Bolt run a race or hearing Yo-Yo Ma play the cello, listening to Dallas's thoughts was to get lost in the sheer joy of seeing a master craftsman at work.

Sometimes the questions became deeply personal. I called him once, in a deep valley, many years ago: "Hey Dallas. My heart is breaking. I cannot fix this. I don't understand it. I am sadder than I've ever been."

There was a long pause. And then a single sentence: "This will be a test of your joyful confidence in God."

I have thought about that sentence a thousand times.

The few other people I spoke to about that valley were empathic and supportive. But that particular sentence is not one that I can imagine coming from someone else's mind or mouth. That sentence I will live with until I die.

Like watching Usain Bolt run a race or hearing Yo-Yo Ma play the cello, listening to Dallas's thoughts was to get lost in the sheer joy of seeing a master craftsman at work. Except it wasn't about the craft. It was about the life and reality and goodness of the God behind the thoughts.

It should not be surprising that on the thinker-feeler continuum, Dallas was all thinker. But I will miss the tremor in his voice, sometimes, when he saw beauty and goodness in God so overwhelming that his heart could not hold it in. The first time my wife, Nancy, joined us for dinner, Dallas began to speak about how good God is. His face fairly glowed. Nancy is not a crier, but when I looked at her, tears were streaming down her face.

For many, he was a little like the wardrobe in Narnia. It's not about the wardrobe; it's about a luminous world to which the wardrobe opens.

Yet you love the wardrobe after all.

Destiny After Death

Dallas would get very impatient with writings that idealize anyone, particularly him. I remember hearing him talk once about his struggle with harboring contempt for people. If he did, it was in a very deep harbor. But God alone knows the human heart. Somebody asked me recently if Dallas realized what a remarkable life he led. It reminded me—as almost everything does—of another of Dallas's observations: "One sign of maturity are the thoughts that no longer occur to you." On the first day of sobriety, a recovering alcoholic will be filled with thoughts of her heroic efforts. After 20 years of sobriety, her mind will be free to think other, more interesting thoughts. Her sobriety will no longer look heroic, only sane—only a gift.

Dallas was free to think other, more interesting thoughts.

He leaves behind his wife, Jane; his son, John; and his daughter, Becky, along with her husband, Bill, and their daughter, Larissa. He leaves behind a vision of the nature of the gospel and the kingdom and moral and spiritual truth that is helping the church, which is always reforming to recapture something of the spirit and message of Jesus. Dallas's work, more than that of anyone I know in our day, is helping us understand more clearly the offer of Jesus, about whom Dallas never ceased to marvel. His influence will ripple along in countless sermons and books and churches and disciples.

"Hey Dallas, what's death?"

"Jesus made a special point of saying those who rely on him and have received the kind of life that flows in him and in God will never experience death. . . . Jesus shows his apprentices how to live in the light of the fact that they will never stop living."

Our destiny, Dallas used to say, is to join a tremendously creative team effort, under unimaginably splendid leadership, on an inconceivably vast plane of activity, with ever more comprehensive cycles of productivity and enjoyment. This is what the "eye hath not seen, nor ear hath heard" in the prophetic vision. It is worth a few dozen read-throughs (found in The Divine Conspiracy).

Dallas also used to say, "God will certainly let everyone into heaven that can possibly stand it." This is another one of those statements that becomes more daunting and frightening and wonderful the more you think about it.

"Keep eternity before the children," his mother said. Dallas kept eternity before us in a way no one else quite has. And now he has stepped into the eternal kind of life in a way he never has before.

I'll bet he can stand it. I'll bet he can.

John Ortberg is pastor of Menlo Park Presbyterian Church, in Menlo Park, California. He is the author, most recently, of Who Is This Man? The Unpredictable Impact of the Inescapable Jesus (Zondervan).