Absolutely no spoilers for Star Wars: The Force Awakens. I promise.

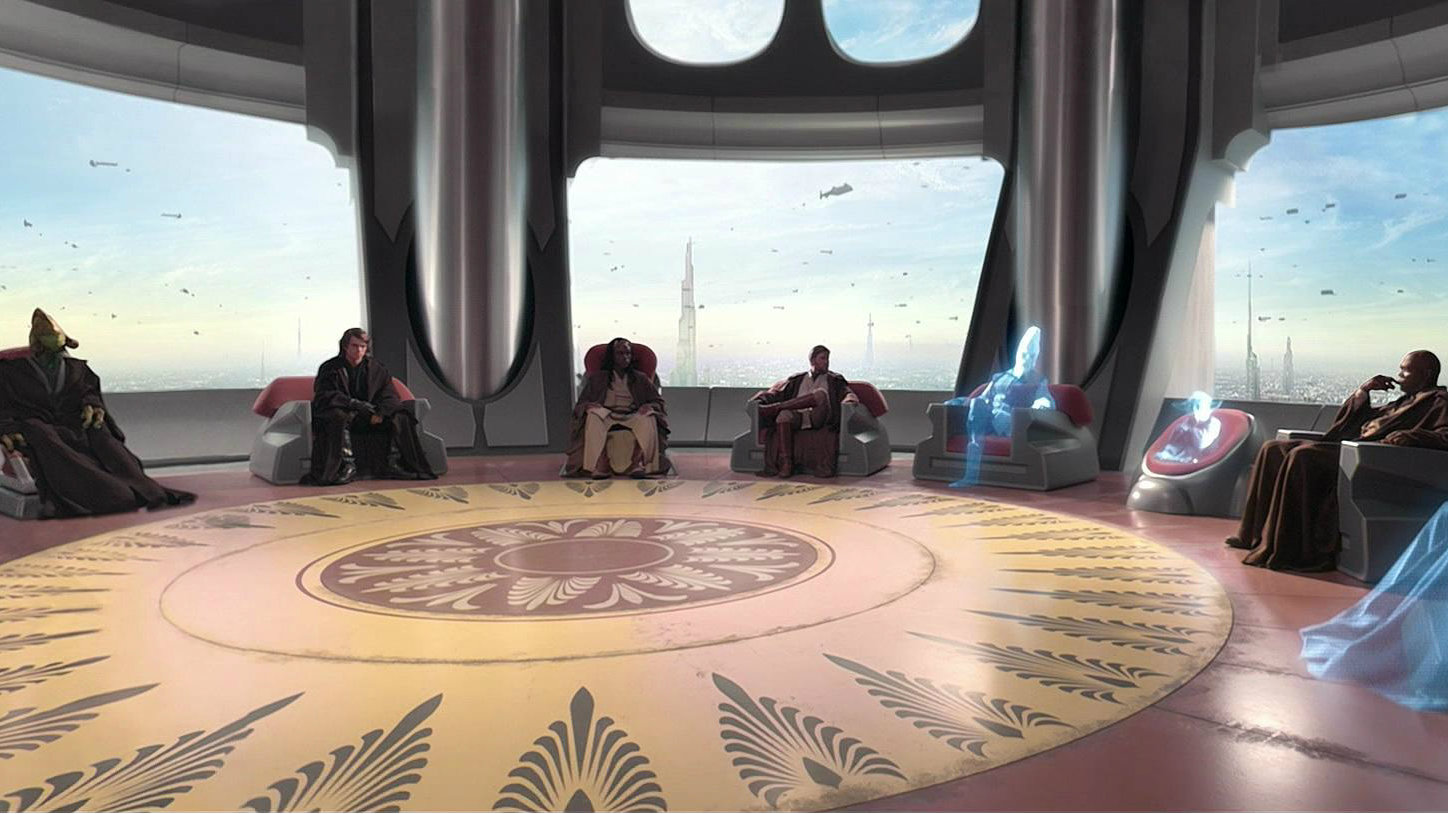

Lucasfilm

LucasfilmIt was inevitable, and truly a sign of our times.

Reuters reports that Berlin’s Zion Church chose an unusual order of worship on Sunday: a Star Wars-themed service, obviously meant to coincide with the global release of Star Wars: The Force Awakens, the seventh episode in the intergalactic space opera. This is notable partly because Zion Church is a landmark in Berlin, a place where Dietrich Bonhoeffer worked at the beginning of the 1930s, according to a Berlin tourism site. (That it was also the fourth Sunday in the Christian season of Advent, traditionally dedicated to contemplating “peace,” seems to have escaped most journalists’ irony detectors.)

I’d wager quite a few Galactic Credits that Zion Church wasn’t the only place in which congregants heard some reference to Star Wars last Sunday, though maybe not everyone toted their light sabers to church. Star Wars: The Force Awakens (our review), the seventh episode in the intergalactic space opera, raked in record-breaking returns from critics, fans, and the box office. And it’s safe to guess that it raked in substantial sermon references and Sunday school discussions as well.

In other words, may the Force be with you. (And also with you.)

Fantasy sagas traffic in mysteries: The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, and The Chronicles of Narnia all feature deep mythologies rooted in religious questions. Even the relatively godless universe of Game of Thrones has some mystical threats lurking around the edges.

Lucasfilm

LucasfilmBut when it comes to religion, Star Wars is on another level altogether. The Jedi system of belief and practice (which is explicitly, and deprecatingly, called a religion right from the start of the series, in 1977’s A New Hope) has captured the imagination of would-be adherents since the original trilogy was released. For $8.99, you can become an ordained Jedi knight. You can get a Jedi marriage license or just officiate a wedding as a Jedi. The Temple of the Jedi Order claims to be a tax-exempt, 501(c)3 non-profit organization. There’s a Wikipedia page for the “Jedi census phenomenon”—in 2001, New Zealand had the highest Jedi per capita, and the threat was still apparently serious enough this summer to prompt Turkey’s top religious body to warn of the spreading of the religion. Those who don’t identify as Jedi knights (or Sith lords) still put on Star Wars-themed weddings and proposals and, of course, conventions.

Even those who don’t go over to the Force’s side—dark or light, take your pick—find themselves curiously drawn to finding how blockbuster series fits into their own religious and cultural beliefs. For instance, at the Jewish magazine Tablet, MaNishtana explored the Jewish themes in the series prior to the release of The Force Awakens, and David Zvi Kalman wrote on what devotees of the Bible and Star Wars have in common. At the AltMuslim blog hosted at Patheos, Irfan Rydhan wrote at length about some elements of Islam that pop up in Star Wars. According to Matthew Bowman today at The Washington Post, Mormons have a particular affinity for the saga that lines up with their interest in science fiction more generally. (The Post also reported that Utahns—inhabitants of the state with the highest density of Mormons—are the country’s biggest Star Wars fans, judging from Google.)

In their service last Sunday, ministers at the Lutheran Zion Church exhorted their congregation to follow Paul's exhortation to overcome evil with good, suggesting that this will mean avoiding violence."The more we talked about it, the more parallels we discovered between Christian traditions and the movies,” Reuters reported the church’s vicar, Ulrike Garve, as saying. "We wanted to make churchgoers aware of these analogies."

Lucasfilm

LucasfilmNot to burst Garve’s bubble, but these analogies have been a topic discussion among Christians for a while—as I suspect she knows, simply because there’s so much literature on the theme. To take just a brief and non-comprehensive sampling from American sources: Dallas Theological Seminary looks at three theological approaches to the series;ThinkChristian explores a Christian theology of the series;PluggedIndives into the theology as well; Al Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, looks at what he terms a collision of worldviews; Decent Filmsexplores the moral and spiritual issues of Star Wars; and you can read books about The Gospel According to Star Wars, The Christian Wisdom of the Jedi Masters, The Power of the Force, Star Wars Jesus, and Finding God in a Galaxy Far, Far Away.

We’ve even explored this in Christianity Today—mostly back in 2005, to coincide with the release of Revenge of the Sith.We talked with Dick Staub, author of Christian Wisdom of the Jedi Masters, and we ran a four-part series by Roy M. Anker on “Star Wars spirituality”—you can read parts 1, 2, 3, and 4.

The drive among those Christians who don’t shy away from the films is to read theology back into the Star Wars universe—to observe how aspects of the series’ spirituality line up with the story told in the Bible. Character and plot archetypes, themes, and precepts are all examined for how they resonate (or don’t) with Christianity.

Lucasfilm

LucasfilmJudging from the proliferation of commentary generated by these explorations, those resonances are certainly there. And that’s interesting, because the links between Star Wars’ religious underpinnings and other religions—Zen Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, and Taoism—are also widely acknowledged.

It seems most every religious group can find something of themselves in Star Wars. That’s no accident. In inventing the mythology of Star Wars, George Lucas drew heavily on mythologist and writer Joseph Campbell’s book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, which traces his theory of the archetypal hero found in many world mythologies. And George Lucas freely admits the religious underpinnings of his universe, though he stops short of calling it “profoundly religious.”

Speaking to Time in a fascinating 1999 interview, he said, “I see Star Wars as taking all the issues that religion represents and trying to distill them down into a more modern and easily accessible construct—that there is a greater mystery out there. I remember when I was 10 years old, I asked my mother, 'If there's only one God, why are there so many religions?' I've been pondering that question ever since, and the conclusion I've come to is that all the religions are true.”

Lucasfilm

LucasfilmSo what’s going on here, really? Why does the series have such a grasp on our religious imaginations and meaning-making engines? A common answer is that people living in a world sucked dry of mystery are attracted to the grand mythology of Star Wars, which integrates (and then flattens to fit Hollywood blockbuster runtimes) so many systems of belief that have resonated with humans across millennia. Good and evil, light and darkness, epic battles and grand mysteries: these things tug at something in our souls, and we want to be part of the story.

Sure. But Star Wars is hardly the only epic mythology to be translated into pop culture ubiquity, and its impact seems to have outpaced even those fanatical adherents of other fantastical and mythological adventures: we don’t see armies of people identifying on the 2001 census en masse as hobbits, for instance, though the world that Tolkien created is far more comprehensive than Lucas's.

So why this story?

Part of it probably has to do with the cultural moment into which it was introduced. Reminiscing on his own first encounter with Star Wars in the New York Times, A.O. Scott—who was eleven at the time—writes that “what ignited in the summer of 1977 may not have been only—even primarily—the love of a particular film. In retrospect, the larger phenomenon of Star Wars represented what looks like the inevitable product of demographic and social forces."

"In 1977," he continues later, "we were innocent of Joseph Campbell and the further annotations Mr. Lucas and others would provide. The allegorical meanings—the battle of good and evil, the mystery of the Force—rest lightly on the jaunty surface of A New Hope. There would be richer intimations of depth and darkness in The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, or maybe, since we were a few years older, we were more inclined to see them.”

And of course the point was that you didn’t just watch the film and go on your merry way. In retrospect, the first trilogy seems to me quite obviously written from the perspective of about a twelve-year-old boy, with the sort of jokes and flirtations and set pieces that seem ripped straight from a pre-teen’s imagination. So you’d go back, over and over again; Scott cites the novelist’s Jonathan Lethem’s essay “13, 21, 1977,” in which he saw A New Hope 21 times when he was 13. You’d better believe that when the film was released onto VHS and Betamax in 1982, many copies got worn out pretty quickly.

Lucasfilm

LucasfilmReturn of the Jedi was released six months before I was born, and my parents weren’t fans, so I didn’t grow up with Star Wars. I first watched them all as a senior in college, IV-VI and then Phantom Menace, then going from Attack of the Clones at my boyfriend’s house straight to the theater for Revenge of the Sith. I was mostly nonplussed, not sure what all the fuss had been about.

But revisiting A New Hope before last weekend’s release, it struck me that probably Lucas's greatest stroke of brilliance (besides R2-D2) was how he told the story.

Because what happens? You get a quick textual prelude—”A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away”—and then bam, you’re in, with the first blasts of the brass in Williams’s score. The opening crawl begins.

But even more brilliantly: wait, what’s this? It is a period of civil war. We’re supposed to know between whom, and who the rebels are, and who we’re supposed to be rooting for. Something has happened before now and, presumably, something will happen in the future. (And with the 1981 re-release, the subtitles were added, and the suspense was heightened: we’re not watching the first episode. It’s Episode IV!)

I can’t even imagine what it must have been like to see this for the first time, the sense of tingly excitement it would send down your spine.

Lucasfilm

LucasfilmThe religious devotion and the drive to shoehorn Star Wars into every belief system has got to have something to do with this framing. We talk a lot about good and evil when we talk about religious systems, but we lose track of how much of being part of any organized religion is also about being grafted into a history. The point of what we do in church—the creeds, celebrating holidays like Christmas and Easter and partaking in the Eucharist, singing the songs, giving our testimonies, baptizing or dedicating our babies—everything about it is about being reminded that we are not the first ones to do this, and we won’t be the last ones, either.

By dropping us into the middle of the action from the start, Lucas made us feel like more must be out there somewhere, languishing in some back closet, the untold story that might have something to do with us. The fact that the trilogies are dropping decades apart gives us plenty of time to imagine, and also to integrate new generations: there are children being born this year who will be able to sit with their grandparents in a few years and watch the movie Grandpa saw fifteen times when he was a boy, and shared with Dad when he got old enough.

There is something deeply religious about this tradition, this recovering of history—something we tend to forget, but that’s buried in our subconscious. And that is a key to The Force Awakens, too.

Before the newest film released last weekend, Alyssa Rosenberg at The Washington Postwrote about how Star Wars has always treated religion—noting, importantly, that “from A New Hope through Return of the Jedi, the Star Wars movies are fundamentally a story about how a dead and discredited religion reasserted itself and proved the truth of at least some of its tenets to unbelievers.”

Lucasfilm

LucasfilmThat’s the most startling thing about The Force Awakens—things have been forgotten or passed into myth (the phrase that’s always the most chilling phrase to me when I enter Middle-Earth or Narnia, too). Mere decades after the last myth was laid down, it’s been forgotten.

Rosenberg continues, “But among my hopes for this renewed wave of Star Wars discussion and debate is that we’ll remember at least the original movies as films about faith and the struggle to hold onto it. Reducing the Force and the Jedi to luck has a way of making that epic struggle from a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away look smaller than it actually was.”

It seems to me that we live in a world more alive to religious questions than it has been in decades—but also one more stripped of historical memory. I wonder, perhaps, if the Star Wars saga, dropping us into the center of the story and then stringing the story along for decades in both our universe and theirs, reinvigorates in us the deeply religious need for a sense of belonging: not just to a group of the living, but to those who’ve come before us, and will come after.

Alissa Wilkinson is Christianity Today’s chief film critic and an assistant professor of English and humanities at The King’s College in New York City. She is co-author, with Robert Joustra, of How to Survive the Apocalypse: Zombies, Cylons, Faith, and Politics at the End of the World (Eerdmans, May 2016). She tweets @alissamarie.