I had to move all the way to New York City before I realized how not-okay it was that most black people in my small North Carolina hometown lived in a sector everyone called Black Bottom.

And as a teenager, I struggled over whether it was okay, theologically, for interracial couples to marry. My pastor preached that mixing races was sinful—an unequal yoking. Something we should be ye not.

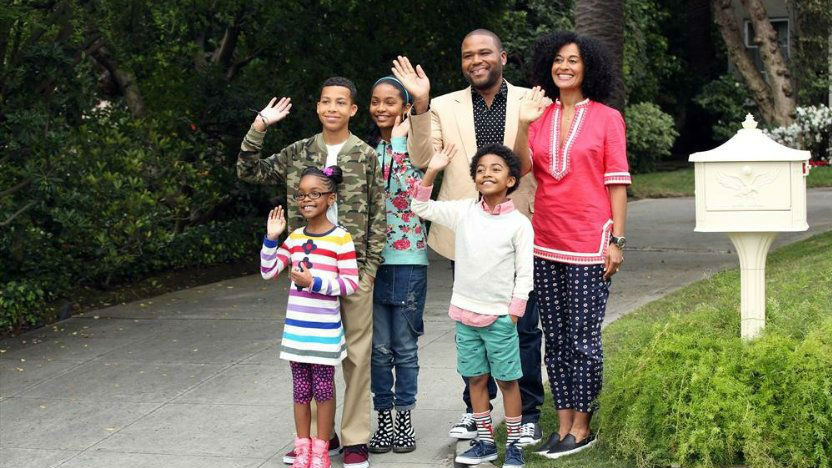

Ron Tom / ABC

Ron Tom / ABCOne of my best friends had one white parent and one black parent, and I used to ask God, “Which side is she supposed to choose?” Segregation officially ended in the 1960s. I had this experience in 2007.

Then I lived in Washington Heights for a year, a mostly-Dominican neighborhood in northernmost Manhattan, and started going by the name “Hey White Girl.” I realized the South isn’t the only place where race affects communities.

I’m not alone. Everyone seems to be trying to figure it out. Are all the advertisements diverse enough? Does a black man have the same opportunity for a work promotion as a white man? Does Taylor Swift’s new music video have an appropriate balance of twerking blacks and whites? Are the Oscars too white?

That tension keeps showing itself in movies and television, too, which is why, as a student studying culture and an aspiring writer, I wonder how writers can speak well about demographics to which we don’t belong. Am I allowed to speak about things that don’t have anything to do with growing up in the South, or being in college, or being a young white American female? Is it wise, if I want to love my neighbor well?

In 2013, the Oscar-winning 12 Years a Slave reminded everyone that slavery happened a long time ago, and that it was horrible. But in 2014, mainstream entertainment shifted its focus to more contemporary racial tension. In 2014 we saw the Bill Cosby blow-up, controversy over Iggy Azalea’s white influence on hip hop, awe at Misty Copeland’s ability to rise to the top of the ballet world, a modern retelling of Annie, a movie called Black or White where two sides of a family fight over which identity the mixed granddaughter will take, Selma, and much more.

I watched and read and listened and talked to friends, and though I kept running into my own questions, I also noticed a few things that crop up repeatedly in our popular culture when we talk about race—things that helped me better understand what we’re all interested in.

“I Don’t Believe in Labels”

Ashley Nguyen / Roadside Attractions

Ashley Nguyen / Roadside AttractionsRaven told Oprah that she is “tired of being labeled.” In the same interview, she said she would not identify as an African-American: “I don’t know what country in Africa I’m from. But I do know that my roots are in Louisiana. I’m an American and that’s a colorless person. ‘Cause we are all people.”

That’s a recurring theme in pop culture, and not just about race. Are labels useful? Are they bunk? Should we get rid of them? Can we? Labeling someone puts them in a box: being a certain way also means being a bunch of other certain ways. Judging from how we talk, a lot of people bristle at the idea of labels. I’m not a Christian. I’m a Jesus-follower. People explore who they are, find that they don’t fit in any particular category in an all-encompassing way, and therefore refuse to identify with any single label. I will always be a person who was raised in the South, is Southern. But I wrestle with that label, because of what other people might think it means about me.

The characters in Justin Simien’s film Dear White People (which was released in theaters in October 2014) wrestle with this. Lionel, a gay black college student, proclaims, “I don’t believe in labels.” Characters struggle with what it might mean to be branded with any label—black, white, mixed, house president, newspaper editor, gay, straight, hopelessly uncool. Characters cling to, shed, or live with indifference to whatever label the rest of the school gives them.

In the film, Coco spends all her time trying to convince those around her that she is not all of the things that a “black” label might imply about her—big hoop earrings, poor grammar, hip-hop obsession. Some people call this label a racist stereotype. Some call its details “majority black culture.” Dear White People says that most black people don’t find themselves fulfilling everything most white people think goes with being “black.”

Ashley Nguyen / Roadside Attractions

Ashley Nguyen / Roadside AttractionsAnd yet: labels sometimes can’t be avoided. I wish I could recreate for you the experience of watching a movie called Dear White People as one of the only white people in the audience. Everyone else laughed at stereotypical white characteristics (being mesmerized by the texture of an afro, for instance), in the way I might laugh at Madea’s word choice in a Tyler Perry movie. In that movie theater, there were two types of people watching—me, and everyone else. We couldn't shed our skin colors at the door. They betrayed at least part of what we were bringing to the story—the different ways we experience the world every day because of our skin color.

Labels can be less than great. But they do exist, and sometimes we can’t get away from them. Pretending they don’t exist doesn't get rid of the problem—it just avoids it, keeping us from confronting racial tension by pretending we're in a “colorless” world, and forgetting that we have both a shared human nature and particular cultural experiences.

So Much “-ish"

Christena Cleveland wrote about what it means to be black-ish for Her.meneutics, and highlighted the problem with upwardly mobile black families being called black-ish. Cleveland wrote, “By subtyping black people who don’t conform to the stereotypical narrative as black-ish, Americans are able to maintain their stereotype of blackness as poor, urban, lacking in formal education, lazy, and dangerous.” The family at the story's center struggles with finding black friends and being marginalized by white people, and also with giving their children “the talk” and deciding whether or not to spank them.

Adam Taylor / American Broadcasting Companies, Inc.

Adam Taylor / American Broadcasting Companies, Inc.My friend Taylor relates personally to the show, and notes that ish implies two absurd things: first, that moderate middle-class success is strictly a white cultural experience; and second, that crime and poor socioeconomic conditions are a strictly black cultural phenomenon. It sounds ridiculous to say it out loud, but as Cleveland (and Taylor and Andre Johnson, the father in Black-ish) points out, that’s exactly what we are saying when we add ish to the black label. You’re kind of black, but not really.

Black-ish parses through (often hilariously) the ways black Americans encounter this situation. In the pilot, Andre Johnson embarks on an escapade to ensure that his black family is “keepin’ it real,” properly adhering to their black cultural identity—“I worry,” he says in voiceover, “that in an effort to make it, black folks have dropped a little bit of their culture and the rest of the world has picked it up.” But his quest is not easy. His wife is mixed-race; the youngest kids don’t notice the color of other kids at school; the oldest son wants to play field hockey and have a bar mitzvah.

Shows and movies like these also seem to stem from a sense that there is something separate and distinct about being black, something worth holding on to. But while I understand that, I still have trouble knowing how I should navigate its reality. Which things can be only black or only white? Can I recognize and appreciate black culture without being offensive? How would I feel if someone called me “white-ish”?

I’m the Realest

One of my best friends from back home, Cambria, is black. She never lived in Black Bottom. Her dad is a sheriff’s deputy and her mom works an office job. She was always on the cheerleading squad; together, her family comprised the entire black population of our church. She now studies Communications at UNC Chapel Hill. Her friends were always white; I remember people saying to her “you’re only black on the outside” and “it must be uncomfortable to always be the only black girl.” The unconscious implication was that she wasn’t a “real” black girl.

Kelsey McNeal / ABC

Kelsey McNeal / ABCWatching Black-ish, I remembered all this. I thought about how ten-year-old Cambria might have received the simultaneous “yo, wut up girl?” and “you’re only technically black” from all the ten-year-old white kids. Even as children, we wondered whether Cambria was “keeping it real” enough, and whether we were, too.

Black-ish points out the tensions both black and white people experience while trying to keep it real (read: figure out who they are) alongside one another. Andre Johnson’s workplace is a comical incubator for all the white people trying to participate in what they stereotypically characterize as black lingo. Lines like “How do you think a black person would say, ‘Good morning?’” and “Wut up Driggity-Dre [failed beat-box attempt]” make us laugh, and also make us uncomfortable. And that's the point. It’s supposed to seem weird and clueless and kind of offensive. In that moment, nobody is “keeping it real” at all.

Navigating racial tension would be much easier if we knew the difference between maintaining cultural identity and appreciating those that are different from our own, and perpetuating racist stereotypes. But, as the students in Dear White People and the clueless people in Black-ish show, as a culture, we still don’t.

Well Now—What Do I Do?

So as a young writer, student, and Christian, I’m still wondering. What can and ought people like me say when writing about movies and TV shows that explore black stereotypes, black cultural identity, black entertainment, black stories? Should I refuse to write about them altogether?

Atsushi Nishijima / Paramount Pictures

Atsushi Nishijima / Paramount PicturesI expect I'll be thinking about this for a long time. But after the events and pop culture of 2014, I keep thinking the key is probably more like what my Southern mama always told me about everything anyway: God gave you two ears and one mouth, honey, so you should listen twice as much as you speak.

How would I have learned that the functional segregation of my hometown was absurd—had not an urban Christian subculture spoken into my Southern evangelical one? Wisdom comes when iron sharpens iron. But I have to first listen. I need others to help me know when I am unwittingly offensive, when I think I know what it means to be a “real” black person or to live life in another’s skin. I don’t know what it’s like to be stereotyped for having dark skin, or to have people think I’m an ish because of upward mobility.

But I can tell you what it’s like to live in contemporary racial tension in the South, or to be a white person watching a movie addressed to people like me. Which might be a useful entry to the conversation, too. We live in the midst of racial tension. I want to listen without judgment and defensiveness. And I want to speak thoughtfully and honestly from my own reality. I want to be careful—full of care—for others.

Rebecca Calhoun was a fall intern with Christianity Today Movies and is a student at The King’s College in New York City.