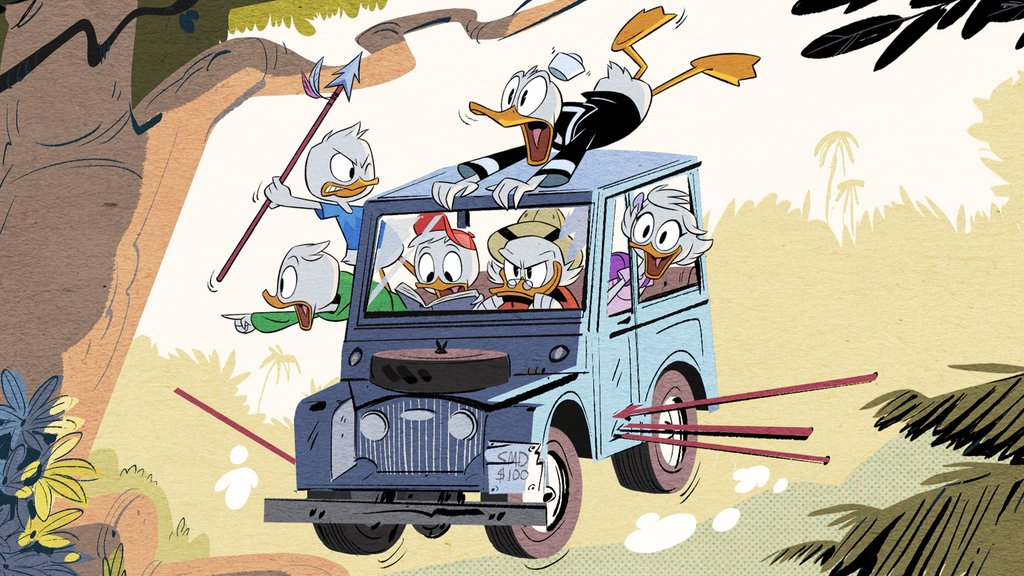

The past few years have been good for those nostalgic for ’80s childhoods—and for those of my age bracket, few cultural products embody that era better than the Disney animated series DuckTales. Based on the long-running Carl Barks comic series Uncle Scrooge, DuckTales followed the exploits of Scrooge McDuck, the miserly (but generally affable) Richest Duck in the World. Despite (because of?) his comfortable socioeconomic status, Scrooge’s wanderlust constantly calls him to adventure across the globe, usually accompanied by his identical triplet grand-nephews Huey, Dewey, and Louie and an eclectic cast of supporting animals—er, characters.

There are countless reasons for childhood fans to look back on the show fondly. Its irrepressibly exuberant theme is surely one of TV’s greatest earworms (even if you never did figure out all the lyrics). In addition, the show’s brilliantly colored animation was coupled with writers who mined storylines from history, literature, and pop culture, placing them in settings that evoked the pulp-action feel of Indiana Jones paired with a flurry of avian puns. It was silly fun, perhaps—yet for many kids, DuckTales might also have been their first exposure to Homer or Shakespeare or Dumas or even H. P. Lovecraft. As an adult, I can still happily show my own kids the same episodes I so thoroughly enjoyed.

You can imagine, then, the mixture of excitement and trepidation among fans when Disney announced it would be fashioning a reboot of this beloved show.

The one-hour premiere, “Woo-oo!” aired Saturday, August 12, replayed the entire day on Disney XD. The new DuckTales is a remake, not a sequel, with different voice talent from the original show (except for Tony Anselmo’s return as Uncle Donald). In the new version, as in the old, Donald Duck sends his nephews to stay with his own Uncle Scrooge, who this time around takes them and his housekeeper’s granddaughter Webby to seek out Atlantis before his rival Flintheart Glomgold can get there.

As I’m already seeing from my own set of acquaintances, reactions to the show derive somewhat from the audience’s expectations. Those prepared to be flexible will appreciate the premiere’s underlying reverence, from its preservation of the original theme song to its familiar style of story arcs to the countless Easter eggs strewn about (especially in allusions to the first DuckTales pilot). Those who wonder why a reboot is necessary, however, may question the new animation style, the rapid-fire style of humor, or the older and more world-wise approach to the triplets and Webby.

Whichever side viewers fall on, though, one strand from the original series remains starkly present in the newer iteration: the danger—and the importance—of family.

Scrooge McDuck made his name and his fortune through risk. This is certainly true of Scrooge in the 1980s version of DuckTales, but it is foregrounded significantly in the reboot as well. We meet a Scrooge who, while still wealthy, is caught in a rut: The initial earnings report he is given suggests that his current business ventures are stable but stagnant. Huey, Dewey, and Louie know him only from his mythical past, as someone who “used to be a big deal.” Like the storehouse of Indiana Jones’s lost ark, Scrooge’s garage is crammed with artifacts from his glory days, all gathering dust.

It is the arrival of the nephews that prompts him to pursue the lost city of Atlantis in an effort to reclaim the enterprising spirit that animated his early career. Their first escapade together leads Dewey to exclaim that “our family is awesome,” prompting their pilot, Launchpad, to affirm that “family truly is the greatest adventure” (right before he characteristically crashes a plane).

This equation of family with adventure has been embedded in the DuckTales DNA from the beginning. In the original show’s two-hour 1987 pilot, “The Treasure of the Golden Suns,” Scrooge bonds with the boys over the course of a treasure-hunting expedition but, as in the new “Woo-oo!,” he is at first reclusive and reluctant. In both instances, the bodily risk of their adventures externalizes the emotional risk. (A curmudgeonly realist may wonder why no one has ever called CPS on Scrooge for child endangerment—but of course, this is beside the point.) In both the 20th-century and 21st-century DuckTales, physical vulnerability in the heroes becomes emblematic of the interpersonal vulnerability necessary for healthy relationships.

At the beginning of “Woo-oo!” the kids are convinced that their life with Uncle Donald is tedious—and indeed, it probably is. However, once we arrive at the episode’s climactic action sequence, we see the seemingly “boring” Donald willingly risk his life to save Dewey from his hubris. His actions demonstrate that, however dull he may seem, he is prepared to live out in deeds the vulnerability that he has already extended to the triplets from his heart.

In DuckTales, then, risk for the sake of relationship is rewarded in a way that risk for pure profit motive is not. The villainous Glomgold is more tentative than Scrooge and hires mercenaries to do the heavy lifting, but he still does journey to Atlantis himself. In the end, though, he is the dark reflection of Scrooge, a wealthy Scotsman (well, Scotsduck), yet always second place—precisely because he puts himself first. He ditches his hired guns—individuals, we learn, who have not known close family relationships—as soon as the opportunity arises, leaving them stranded (and reliant, ironically, on Scrooge’s generosity).

As with the first DuckTales, the definition of “family” in the reboot is somewhat loose. There are no traditional nuclear families to be seen, and the core relational unit includes many non-blood-relatives: Mrs. Beakley, Webby, Launchpad (and, reports suggest, many other returning subsidiary characters).

What remains most significant throughout, though, is the emphasis on love as a self-sacrificial quality that demands hazard. “Greater love has no one than this,” claims Jesus, “to lay down one’s life for one’s friends” (John 15:13). Shortly thereafter, he would serve as our example in backing up these words with action. In Christian thought, this love, directed toward the ultimate goal of God’s service, has been called the theological virtue of charity. No one but Christ has perfectly exemplified it, and the best Christians since him can only even approach his standard because of the work of divine grace in transforming their desires.

Yet in their own ways, even unbelievers can show a form of such love. It may not be charity, as it is directed toward the wrong end. But, as even Thomas Aquinas could acknowledge, those outside the faith can “do those good works for which the good of nature suffices.”

What’s good for the goose is good for the gander. In a small, silly, cartoonish way, the characters of DuckTales have already begun to show shadows of the “greater love” that Jesus commends to his disciples. Manifestations of such a love are the real heart of the show, beyond clever bird puns or animation style—or even an amazing theme song.

And that’s just ducky for me.

Geoffrey Reiter is assistant professor of English at the Baptist College of Florida and associate editor for Christ and Pop Culture. He holds a BA in English from Nyack College and a PhD in English from Baylor University, along with an MA in church history from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary.