To his credit, Alec Ryrie has braved treacherous waters and written a history of Protestantism. Recognizing that such a voyage can founder on the shoals of Protestant identity, he has studiously avoided theological accounts in favor of two root metaphors. There is no Protestant principle at work; rather, there is a Protestant ethos or mood.

For Ryrie, Protestants are lovers and fighters. The former notion refers to the dramatic experience of grace to which Protestants repeatedly testify, while the latter underscores their willingness to protest anyone who might challenge their fidelity to Scripture. From this vantage point, Protestantism’s commitment to the centrality of the Bible turns on viewing it as both a source of inspiration to be read devotionally (a love affair) and a sword to be sharpened and utilized polemically. It is this spirituality, which Ryrie calls “a deeper unity of mood and emotion,” that holds Protestants together as a single family.

This approach to Protestant people and movements allows Ryrie to explore “distant cousins” like Mormonism and Jehovah’s Witnesses while also acknowledging that the shared genetic markers are slim indeed. His brand of social history is a welcome reprieve from other histories that tend toward doctrinal identity. Although he never says it, Ryrie grounds the essence of Protestantism within its pietist impulse. Like H. Richard Niebuhr before him, he sees Protestantism as more movement than institution, more spirituality than confession, more behavioral than doctrinal. This explains why he concludes that Pentecostalism is now global Protestantism’s “main engine.”

The Modern Age and the Protestant Spirit

As social and political history, Protestants succeeds in fulfilling Ryrie’s ambition to show how understanding Protestantism is necessary to any explanation of the modern age. The two root metaphors branch out into three emphases that ground Ryrie’s argument.

On the basis of their love affair, awakened in an encounter with divine grace, Protestants have cultivated a spirit of free inquiry that privileges conscience constrained by Scripture alone and interpreted through Spirit-driven experiences. Acts of protest stem from this privileging of conscience, making Protestantism an “open-ended, ill-disciplined argument” that restlessly surges forward in new modes. The second emphasis is a tendency toward democracy, by which Ryrie means the duty to challenge political and religious authority on the basis of the freedom to pursue God according to the dictates of conscience. Acting on this duty requires a participatory politics.

Finally, Ryrie suggests that Protestants instinctively want to be left alone to pursue God, and so they strive to carve out the political space within which to do so. Regardless of their politics, they prefer an apolitical way of existing, which has led to emphases on limited government. Protestants are often reluctant participants in political life, mainly because they desire to preserve free inquiry and freedom of conscience. Rather than drawing straight lines from Protestant identity to free-market economics, Ryrie suggests that this ethos produced a habitat conducive to its emergence. For these reasons, it becomes almost impossible to understand how the modern age arrived without reckoning with the spirit of Protestantism.

Ryrie’s argument unfolds in three parts. The first part addresses the Reformation age, which takes the reader from Luther’s breakthrough up to the 1660s. In the second part (the Modern Age), Ryrie turns back to the early 1600s to explain the rise of Protestant pietism in its German and English varieties, concluding with an examination of liberal and conservative Protestantism in the 1950s. The final part (the Global Age) breaks from the chronological pattern to explore Protestantism’s geographical expansion by offering three vignettes of South Africa, Korea, and China, followed by a tour of global Pentecostalism. A final chapter briefly explores Protestantism’s future before returning to the basic point that Protestantism is a family of squabbling identities, cultures, practices, and institutions emerging from a direct encounter with divine power, “that old love affair.”

Ryrie’s skill at writing, seasoned with just enough wit, keeps the narrative moving even through denser sections on the English civil war or the minutiae of the Third Reich. Titling the chapter on Reformed Protestantism “the Failure of Calvinism” alerts the reader to Ryrie’s mischievous sense of humor (he’s actually talking about Calvinism’s failure to produce Protestant unity). In the same chapter, he briefly mentions the German reformer Martin Bucer as the one Thomas Cranmer invited to England during the heady and hopeful years of the boy-king Edward VI, “where the climate promptly killed him.”

At the same time, Ryrie’s rhetoric can outpace the interpretive moves he makes, stretching the argument to the bursting point. Luther’s Two Kingdoms model emerges throughout the book to underscore the apolitical nature of Protestantism. This causes Ryrie to search for signs of Luther, which he finds everywhere like footprints in the sand—from Locke’s writings on tolerance to early Pentecostalism’s view that politics is rotten and worldly.

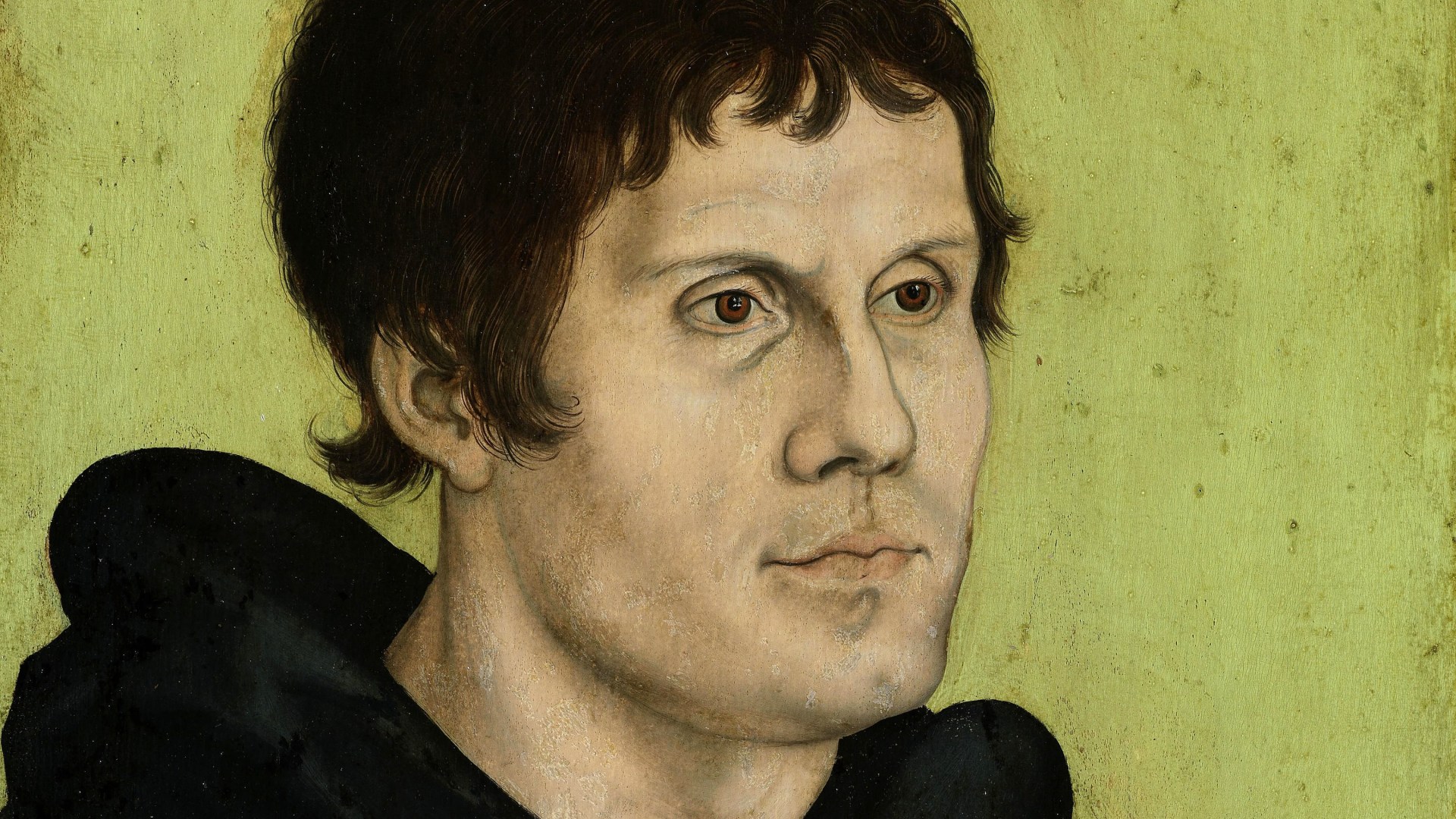

Throughout the book, Ryrie rarely moves far from his root metaphors. Luther’s two principles of sola fide and sola scriptura come to illustrate an intoxicating passion for a God who loved him in his sin-sickness and his disregard for church and tradition. The paradox Luther discovered, one that now stands at the heart of Protestantism, is that one only finds peace by abandoning all and standing alone before the God, who has become flesh in Christ and is the only one worthy of attention. It is this extravagant love that causes Luther to treasure the Bible as a love letter to which his conscience—that is, his desire—was captive. Such a love, according to Ryrie, made Luther a brawler.

Under Ryrie’s gaze, German Pietism turns out to be “a rekindling of the love affair with God that had been Protestantism’s beating heart since Luther,” and Friedrich Schleiermacher’s modern liberal gloss on Christian theology becomes an effort to rescue Protestantism’s “original love affair with God from dead formulae.” In the Protestant ethos, politics is at best secondary, a defensive posture meant to preserve the heart of the movement: its message of salvation and divine power. The power of Martin Luther King Jr.’s vision rested in his capacity to leverage a Protestant spirituality of love in the service of his protest, on the basis of his own experience of God’s presence.

A Family Affair

As illuminating as Ryrie’s approach is, it is not without cost. His focus on post-Reformation social and political history obscures the many medieval antecedents of Protestantism and their effect on the resulting Protestant DNA. The reference to John Bunyan’s desire to drink water “out of my own cistern” as an appeal to experience has its medieval counterpart in Bernard of Clairvaux’s instruction to Pope Eugenius that the wise man will first and foremost drink from his own well. Bernard meant to underscore the ancient maxim to know oneself, but he and other 12th-century writers used it to reinforce an entire spirituality constructed around love and the ecstatic embrace with the bridegroom. With its focus on ecstatic union, this spirituality of love was transmitted to Luther through the religious populism of late medieval women and men. If Protestants are lovers, then, they were taught to love by their medieval predecessors. Surely medieval Christianity shares more family resemblances than Mormonism.

A second consequence of Ryrie’s approach is that it tends to separate narratives that should be kept together. This is apparent in the decision to change strategies in the final part and focus “case studies” of globalization rather than continuing with a chronological and genealogical account. One result is the fragmentation of the late 19th-century holiness movement, which Ryrie connects to fundamentalism in one chapter and then treats as a precursor to Pentecostalism in a later chapter. One would never know that R. A. Torrey, who appears as an example of the holiness movement, was also an architect of The Fundamentals.

Even more egregiously, Ryrie claims prohibition as an achievement of conservative Protestantism, disregarding Frances Willard and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the largest organization of women in the United States in the late 1800s. Under Willard’s leadership, temperance and prohibition were part of a larger agenda that included the right of women to vote, all in the name of promoting the Wesleyan vision of social holiness. In general, Ryrie’s approach to the holiness movement offers partial glimpses of certain figures and events while leaving out key leaders like Willard, D. L. Moody, and William and Catherine Booth, co-founders of the Salvation Army.

These shortcomings notwithstanding, we should applaud Ryrie’s courage to tell the tale of Protestantism. He clearly relishes portraying the dynamics of Protestant family life in all of their glory and ignominy. After all, as Ryrie admits, Protestantism is his family, and like any good minstrel he has woven together an epic tale that not only reminds Protestants of their relations and all of their conflicts but calls them back to a love divine, all loves excelling.

Dale M. Coulter is associate professor of historical theology at Regent University’s School of Divinity.