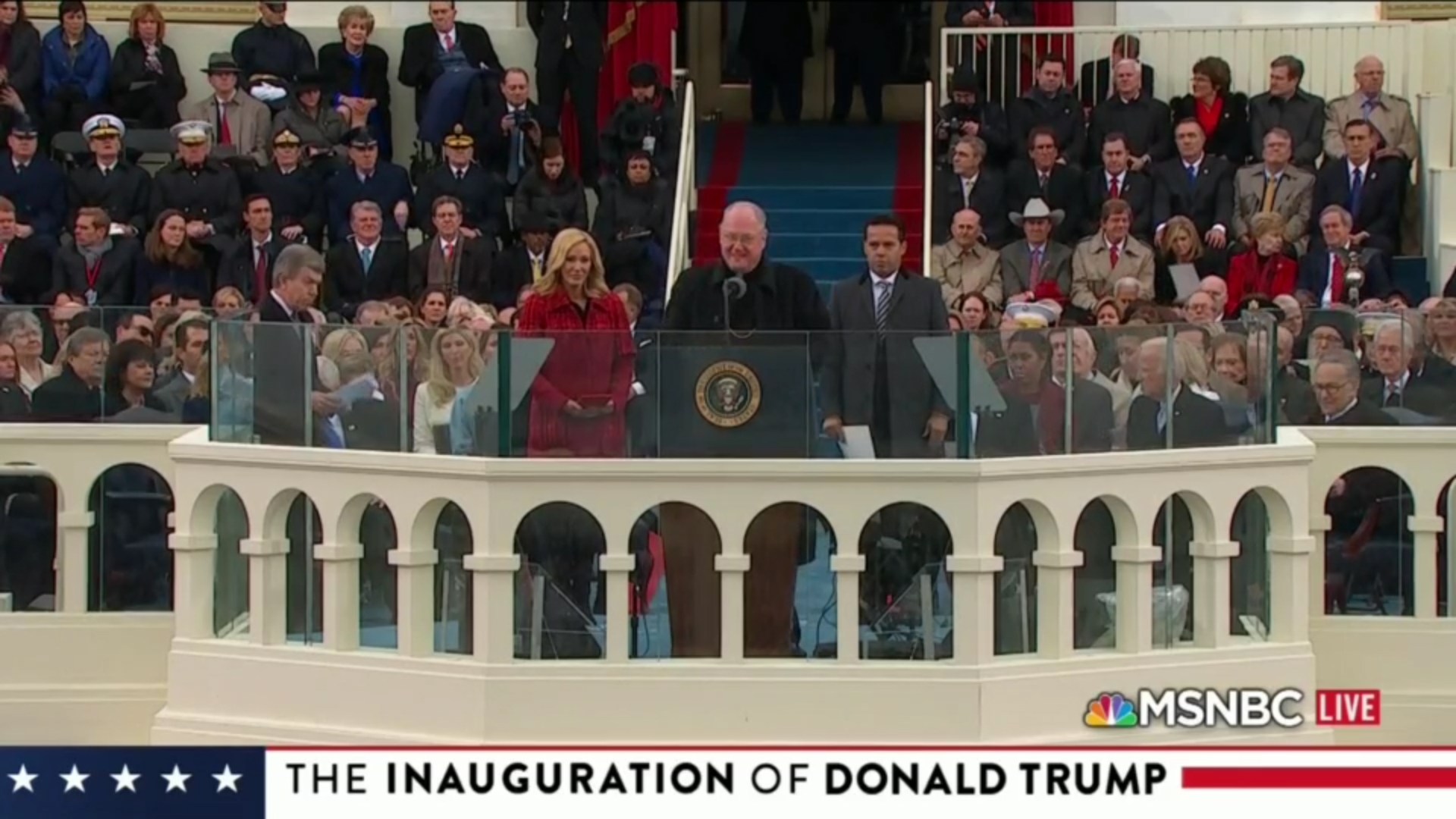

When Cardinal Timothy Dolan moved to the podium to pray at President-elect Donald Trump’s inauguration, his prayer may have struck you as oddly familiar.

The passage he prayed from is very similar to Solomon’s prayer for wisdom in 1 Kings 3. But, it’s not the version Protestant Christians know, because it’s not in the Bible that we read.

It comes, instead, from the Wisdom of Solomon, a book included in the Catholic and Orthodox churches’ Old Testament, but not included in Protestant churches’ Old Testament.

Wisdom of Solomon is one of the books found in a collection of early Jewish writings that Protestants call “The Apocrypha.” The books included in this collection were mostly written between 250 BC and AD 50; some within the land of Israel, others in a diaspora context (Jews living outside of Israel); some in Hebrew, others originally in Greek. The collection includes historical books (1 and 2 Maccabees), wisdom texts (Wisdom of Ben Sira, Wisdom of Solomon), liturgical works (Prayer of Azariah, Song of the Three, Prayer of Manasseh), historical fiction (Tobit, Judith, Susanna, Bel and the Dragon), prophetic literature (Baruch), apologetics (Letter of Jeremiah), and a much more “religious” version of Esther. While these are all Jewish texts, it was the reading practices and canonical debates of Christians that resulted in these representative texts becoming identifiable as a “collection” at all, because they are drawn from a much larger body of Jewish literature from the period.

Catholic and Orthodox Christians read the books of the Apocrypha as part of their Old Testament. They sometimes refer to these as the “Deuterocanonical” books—a “second canon,” not in the sense of having lesser importance, but in the sense of their canonical status being settled late in the game. There were always voices in the church that recommended adopting the shorter canon, used in the Jewish synagogue, as the Christian Old Testament. Jerome, who translated the Bible into Latin, was the loudest voice in this regard. Augustine, however, championed the church’s continued use of those other texts that had nourished its faith, and his voice for the most part prevailed, although some would see the definitive ruling coming only much later at the Council of Trent in 1546.

The question became pressing once again as the Protestant Reformers sought to base their faith and practice solely on Scripture—and thus needed to clarify what would be included as Scripture. They returned sharply to Jerome’s view, which had continued to be voiced even within the Catholic Church. One motivation for this might have been the fact that a number of Catholic practices that were particularly problematic for the Reformers—like saying masses for the dead, seeking the intercession of the dead saints, and building up a treasury of merits—found some support in books like Tobit and 2 Maccabees.

Should Protestants read the Apocrypha? Even though the Protestant Reformers followed the shorter Old Testament canon used in the synagogue and recommended by Jerome, they continued to hold the Apocrypha in high esteem. Martin Luther translated these books for his German Bible, though he published them in a separate section. In his preface, he recommended them highly: “These are books that, though not esteemed like the Holy Scriptures, are still both useful and good to read” (from Luther’s Preface to the Apocrypha). He was especially keen on Wisdom of Solomon and 1 Maccabees. The King James Version of 1611 likewise included a translation of the Apocrypha between the Testaments, and the Church of England continued to read from several of its books throughout the church year. The author of the preface to the Old Testament of the 1546 Geneva Bible wrote that “the Apocrypha is not to be despised, insofar as it contains good and useful teaching.”

As the more economical practice of printing Protestant Bibles without the Apocrypha became increasingly widespread, the opportunity for acquaintance with these books was lost and they fell under greater and greater suspicion due to general anti-Catholic prejudice. Protestants would do well, however, to return to the more balanced view of these books held during the Reformation itself and to read these books, not as Scripture, but nevertheless as an invaluable resource for several reasons.

First, they open windows into a Judaism that was much more current with the Judaism into which Jesus was born and out of which the early Christian movement was birthed than the books of the Old Testament do. Acquaintance with this literature will reveal a greater continuity between the ethics and worldview of Jesus and the New Testament writings, and the Judaism of the period than we would otherwise discern from reading only the Old Testament. On the other hand, those who read these texts will also have a more precise grasp of the points at which Jesus and the early church stood out from the convictions and practices of their environment.

Second, these books exercised a significant influence on the church of the first four centuries, being read as Scripture by many important church fathers and at least as inspirational literature by the rest. The stories of the martyrs in 2 and 4 Maccabees fueled Christian courage to face the same challenge. The reflections on the figure of Wisdom and her relationship to God in Wisdom of Solomon and Baruch provided raw materials for the development of Christology and the doctrine of the Trinity. The defense of the worship of One God and the attacks on the folly of idolatry in Wisdom of Solomon and Letter of Jeremiah continued to inform Christian apologetics. Furthermore, the historical information in 1 and 2 Maccabees helps illumine murky texts in the Protestant Old Testament canon, like Daniel 7 and 11.

Pious Jews of the Second Temple Period wrote a great deal more literature beyond these books, for example, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Pseudepigrapha, the works of Philo and Josephus, all of which contributes to our knowledge of the world of the early church. The collection known as “the Apocrypha,” however, especially commends itself to all Christians on account of the esteem in which so many Christians have held it since the earliest church. Therefore, Luther’s position on the Apocrypha, from his preface to 1 Maccabees, seems to me to be the soundest for Protestants to take: “It is useful for us Christians also to read and know it.”

David A. deSilva is Trustees’ Distinguished Professor of New Testament at Ashland Theological Seminary in Ohio and the author of over 20 books, including Introducing the Apocrypha (Baker Academic, 2002), The Apocrypha (Abingdon, 2012), and Day of Atonement: A Novel of the Maccabean Revolt (Kregel, 2015).