I enter the nave of St. Mary’s Episcopal Church right before the service begins. I slip into the end of a pew beside a man I don’t know, surrounded by others I don’t know. I am younger than most of those present. I face a dozen or so women and one man who appear to be in their fifties and sixties in the pews opposite mine. The lights are dimmed, but the afternoon sun shines through stained-glass windows. Three windows on the wall in front of me depict scenes from Jesus’ life and ministry. A tall, brass candelabra in the center of the wooden chancel floor holds a single white candle, its flame flickering. The organist plays a prelude. No one stirs.

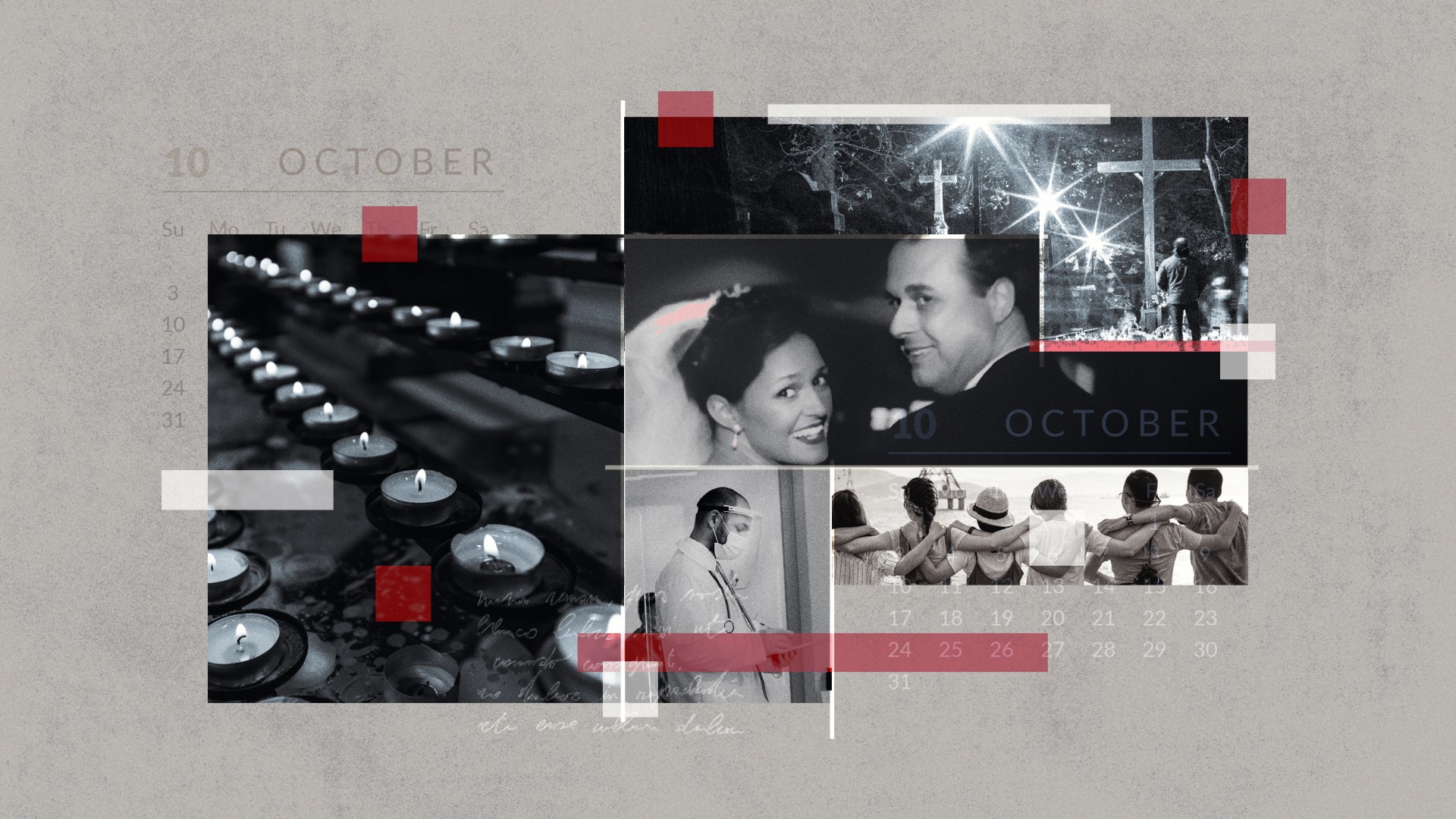

It was All Saints’ Day 2019, and I had come to sing hymns and recite prayers and remember those who had died. I had no idea that we were months away from a global pandemic that would affect millions of people across the world and take the lives of more than 215,000 Americans. I didn’t know my father would be one of those who died from complications of COVID-19. I didn’t know I would be adding him to the list of whom I will remember on November 1, 2020.

My dad wasn’t Episcopalian or Anglican. For several years when I was growing up, my father, mother, brother, and I sat in the last row in the sanctuary balcony at First United Methodist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, where my dad volunteered to oversee the sound system. Whenever we sang congregational hymns, he swayed slowly from side to side because he wasn’t great at standing still. I’d join him sometimes in his movement right to left, right to left, like human metronomes as we sang familiar hymns like “Holy, Holy, Holy,” “I’ll Fly Away,” and “Amazing Grace.”

We sang those hymns while my dad was dying.

My mother, her sister, and my dad were in his hospital room in Panama City, Florida. My husband, children, and I called in from our home in Birmingham, Alabama. My brother and his family joined from their homes in distant parts of the country. Together, we cried, prayed, and sang. With broken hearts, we helped usher him into the everlasting. My dad was sedated and couldn’t respond to our tears, words, prayers, and songs, but the nurses and doctors told us he could hear us. We hoped he could hear us.

All of us who grieve loved ones who died in 2020 because of COVID-19 or any other reason carry a common sorrow. We share similar expressions of lament. We belong to each other in our grief.

The faith practices, prayers, and traditions of All Saints’ Day reinforce the theology of the communion of saints by reminding us that as members of the body of Christ, we belong to each other and to God in this life and beyond. This day reminds us of the truth of Romans 12:5, “So in Christ we, though many, form one body, and each member belongs to all the others,” and Ephesians 4:2–4: We must continue “bearing with one another in love. Make every effort to keep the unity of the Spirit through the bond of peace. There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called to one hope when you were called.”

A bulletin insert provided by The Episcopal Church explains how we set aside All Saints’ Day to “remember and commend the saints of God,” especially those who aren’t recognized at other points in the church year. Over time, All Saints’ Day came to be a day of remembrance and honor for the dead: “all Christians, past and present; all saints, known and unknown.” We sing hymns reserved for this day. One such hymn includes these lyrics: “Who are these like stars appearing, these before God’s throne who stand? Each a golden crown is wearing; who are all this glorious band? Alleluia! Hark, they sing, praising loud their heavenly King.” I love the image of the saints as stars and a heaven that’s brighter now than it was a year ago. The idea of a heaven that grows brighter every hour, every day takes away a bit of the sting of death.

The theology of the communion of saints and All Saints’ Day also sustains me in my grief. I read Scriptures, pray prayers, and recite creeds with members of my congregation and others around the world and know their moments of faith carry me when I’m unable to travel the road of suffering on my own. I hear about others who have lost loved ones this year, and I know I’m not weeping alone. My prayers ferry others when their enormous sense of loss interferes with their ability to believe God is still good. And their prayers ferry me.

All Saints’ Day reminds us that the gospel joins and connects those of us who confess Jesus as Lord and Savior. The gospel and who we are in Christ proclaim we are children of God. And if we are all children of God, we are all siblings in God. We have the same spiritual DNA, the same family stories, and the same family name: Beloved. Regardless of whether or not we observe All Saints’ Day or other feast days and liturgical seasons from the church year, all Christians—all who have died, all who live, and all who are yet to be born—belong to each other as surely as we belong to our triune Lord.

All Saints’ Day also gives me hope. Hope has been pretty hard to come by this year. But on this feast day, God reminds us of our ultimate destination. Having hope in the eventual full realization of the kingdom of God doesn’t take away our sorrow and grief, but it becomes a sort of comrade. It takes our hand and leads us toward what’s true. Yes, we have lost so much, and we will continue to experience loss. But we have also received good things, and we will continue to receive good things. In Christ, we receive God’s presence, comfort, love, grace, and mercy. We receive the ability to empathize and sympathize with others who are where we have been or where we are now. We receive assurance that this place we inhabit isn’t our final stop.

We might find comfort in one of the Scripture readings from All Saints’ Day on November 1, 2020. Revelation 7:13–17 (NRSV) speaks of our shared script and what will eventually become of all who are included in the cast. It sets the stage and outlines the plot:

Then one of the elders addressed me, saying, “Who are these, robed in white, and where have they come from?” I said to him, “Sir, you are the one that knows.” Then he said to me, “These are they who have come out of the great ordeal; they have washed their robes and made them white in the blood of the Lamb.

For this reason they are before the throne of God,

and worship him day and night within his temple,

and the one who is seated on the throne will shelter them.They will hunger no more, and thirst no more;

the sun will not strike them,

nor any scorching heat;for the Lamb at the center of the throne will be their shepherd,

and he will guide them to springs of the water of life,

and God will wipe away every tear from their eyes.”

When we are citizens of the new heaven and new earth, we will be united in ways that are no longer overflowing with mystery. We will receive permanent shelter from our God. Our appetites will be forever satisfied. Our thirst will be eternally quenched. Our Shepherd will guide us toward everlasting life. And all of our tears—including our tears of grief and lament for our loved ones who have died—will be wiped away.

Charlotte Donlon is a writer and spiritual director living in Birmingham, Alabama.

A portion of this essay is adapted from The Great Belonging: How Loneliness Leads Us to Each Other (Broadleaf Books, 2020).