I come from a long line of freedom-loving religious nonconformists. I can trace my lineage back to Swiss Anabaptists who fled Europe for Pennsylvania in the late 1600s, and I grew up in an unaffiliated congregation in the same commonwealth 300 years later—working and worshiping under the certain belief that God had endowed me with “certain inalienable rights.” I’ve also spent my adult life ministering in churches descended from English Baptists (whose exact relationship to continental Anabaptist groups is best left to historians).

Today, I live in Virginia, where Thomas Jefferson drafted the 1777 Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom that eventually gave us the religious liberty clause of the First Amendment—a proposal spurred in part by Virginia’s state-sanctioned persecution of Baptists. Despite this pedigree, I find myself perplexed by my fellow Baptists, who seem to think that our soul liberty—the belief that the individual is directly responsible to God in all matters of faith and conscience—stands opposed to our communal responsibilities. During the pandemic, for example, tension between individual rights and the common good emerged as religious liberty issues. When civil authorities placed limits on large gatherings, including church worship services, Baptistic pastors like John MacArthur cited soul liberty and local church autonomy as their reasons for opposing such measures.

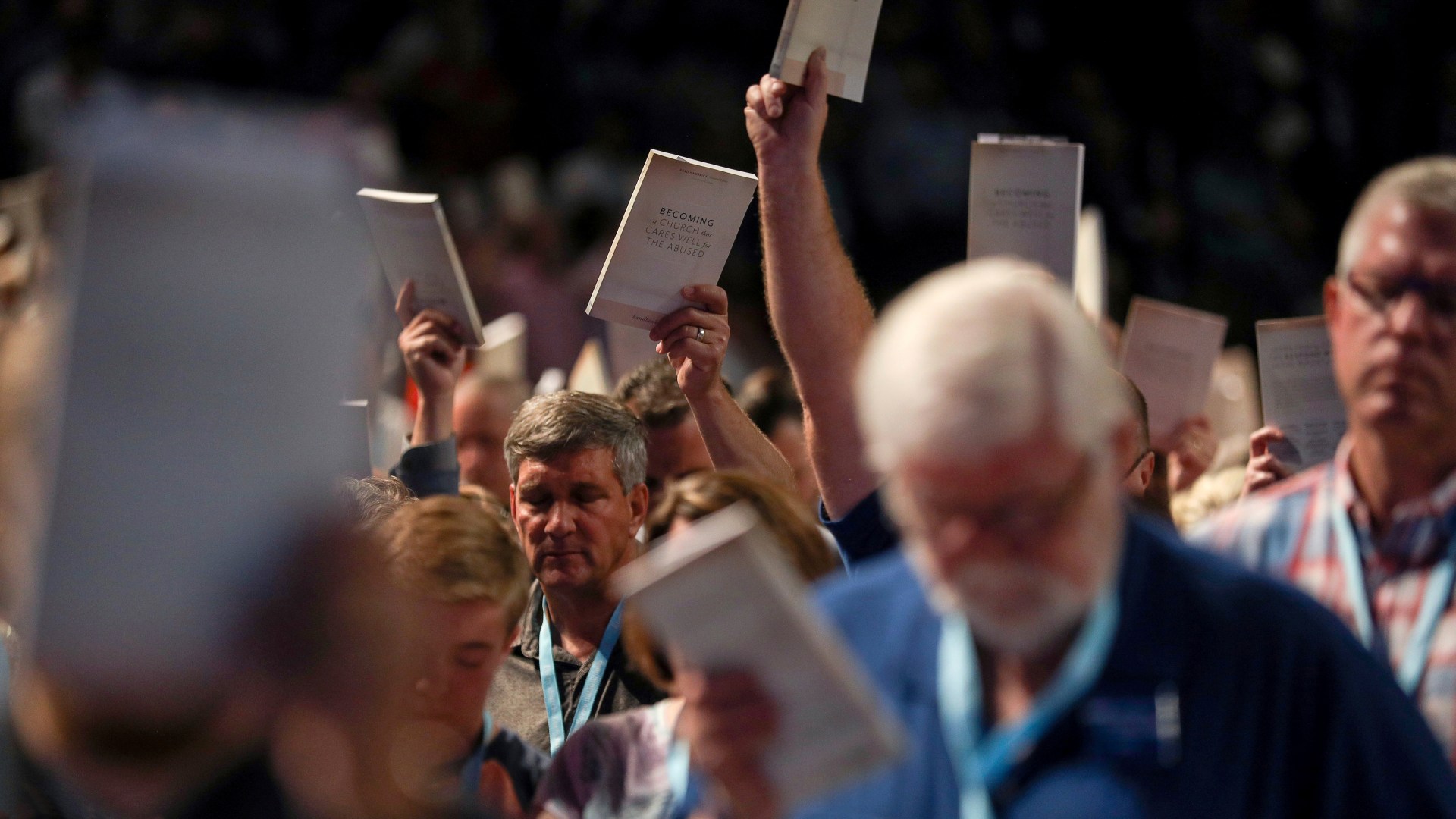

But another, more pressing question about independence confronts the messengers of the Southern Baptist Convention this week as they gather for the annual meeting in Nashville. In early 2019, Houston Chronicle special investigation detailed how sexual predators used the autonomy of SBC-affiliated churches to prey on members, moving from church to church to escape accountability. At the time, SBC leaders like Russell Moore and then SBC president J. D. Greear called for structural changes, including the formation of a database of known predators. Others, like former SBC Executive Committee vice president and general counsel Augie Boto, opposed such measures, suggesting that the autonomous nature of Baptist churches would itself make such changes impossible. And in recently released audio from an October 2019 debriefing of the Caring Well Conference, Ronnie Floyd, president and CEO of the SBC Executive Committee, objected to the public discussion of a mishandled abuse case, suggesting that it would disturb “the base.” In some churches, such matters could be left to denominational heads to sort out, freeing “the base” from the supposed unseemliness of it all. But how does the conversation change when a church tradition is built on the democratization of power? How does responsibility shift when the people in the pew are the ones in authority? Instead of protecting “the base” from such difficult conversations, Baptist polity actually draws them in. So while it is true that the majority of Southern Baptists don’t know the names of convention leaders and employees, it is also true that the majority of Southern Baptists deeply value the autonomy and individual freedom they enjoy through voluntary association.

Baptists believe church authority resides in individual members filled with the Holy Spirit. That is precisely why those same members—or in Floyd’s words, “the base”—cannot pass the buck. To forgo the responsibilities of autonomy while taking its privileges would multiply injustice upon injustice. All of this has implications for the work SBC messengers must do in Nashville this week. As representatives of their own individual churches, the messengers might be tempted to excuse themselves from the larger questions facing the convention, including claims that key leaders mishandled abuse and even harassed and belittled survivors. But to forgo responsibility for these matters would be to deny core tenets of Baptist doctrine and polity.

As sex abuse survivor and advocate Rachael Denhollander puts it, the “SBC’s theology of autonomy and representative-based structure is intended to create a system with extra accountability—where power isn’t concentrated in a few, but rather placed on the consciences of all.”

In many ways, the history of Baptist polity runs parallel to the history of modern democratic ideals. Civil values like individual freedom, the right to vote, and local representation find religious parallel in soul liberty, congregationalism, and local church governance. Ideas that would have been radical in any other time (radical enough to get you kicked out of 17th-century Europe, for example) are today the hallmark of American religious life. But to understand the responsibility that “the base” will have in Nashville, we have to understand the relationship between power and accountability. In a given community—whether family, church, or nation—a person’s responsibility is proportionate to the power they hold in it. The greater power you wield, the more responsible you are to wield it for the well-being of others, especially for those who do not have power to protect themselves. This dynamic is why it’s particularly shameful for those with power to act the coward. It is one thing when the weak can do little in the face of corruption. It is another thing when the powerful choose to do nothing and instead turn their energies and attention to consolidating their own power. Conversely, this privilege-responsibility dynamic is also why it’s particularly heroic when those without power commit themselves to fighting evil and pursuing systemic change, risking what little they have for the good of all. Ultimately, resisting evil does not depend on having a certain structure or polity. It depends on the moral choices of those within the structure and polity. Andy Rowell, a professor of ministry leadership at the historically Baptist Bethel University, makes a related observation. “When teaching seminary students to navigate polity and power in congregations and denominations,” he commented, “I emphasize that a structure cannot make up for bad character. Even the ideal system will fail without compassion, collaboration, oversight, wisdom, sobriety, and experimentation.” So while members are not individually responsible for the sins of others, we are responsible for how we respond to those sins. We are responsible for what we do when they come to light. Even if we lack the power to bring about justice on our own, we must stand on the side of justice. Because while particular leaders may be guilty of particular sins, the choices of the individuals around them determine whether these sins go unchallenged. In this respect, we need not be actively engaged in corruption to be complicit with it. We simply have to do nothing when we learn of it. We simply have to look the other way. “Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim,” writes Nobel laureate and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel. “Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.” Within Baptist polity, members are responsible for those we entrust with power, those we authorize to work on our behalf. We are responsible to select good leaders, and we are responsible to hold them accountable to use their power well.

Reporting on the work of the Executive Committee in their plenary session today, Kate Shellnutt summarized public comments from the committee’s secretary, Joe Knott, who opposes widening investigations of abuse cases. Knott believes such a move would challenge church independence and suggests that SBC churches are safe from abuse because Sunday schools are run by kids’ mothers and grandmothers.

But our Baptist commitment to soul liberty and local church autonomy means greater structural accountability, not less. Leaders like Knott, who refuse to take the steps necessary to ensure transparency, must be removed. It’s up to the individual messengers to ensure this happens. Whether the person in the pew can carry this kind of moral and ethical weight is the purview of philosophers. That we do carry it is the reality of Baptist polity. In a recent interview, Gladys Sicknick, mother of slain Capitol police officer Brian Sicknick, raises a crucial question for all who enjoy the benefits of individual liberty—whether political or soul. After decrying congressional leaders for their response to the January 6 attack, she asks, “Do they really want to live in the country they’re creating? Do they want their children to grow up like this?” Sicknick understands what too many of us seem to have forgotten—including those who champion soul liberty and local church autonomy. We are right now, in real time, creating the world that we live in. What we consent to, what we allow, is who we are. And the choices we make today will birth the communities and churches our children inherit tomorrow. May God grant “the base” wisdom and virtue this week in Nashville. May they steward both the privileges and the responsibilities of membership well.

Hannah Anderson is the author of Made for More, All That’s Good, and Humble Roots: How Humility Grounds and Nourishes Your Soul.

Speaking Out is Christianity Today’s guest opinion column and (unlike an editorial) does not necessarily represent the opinion of the magazine.