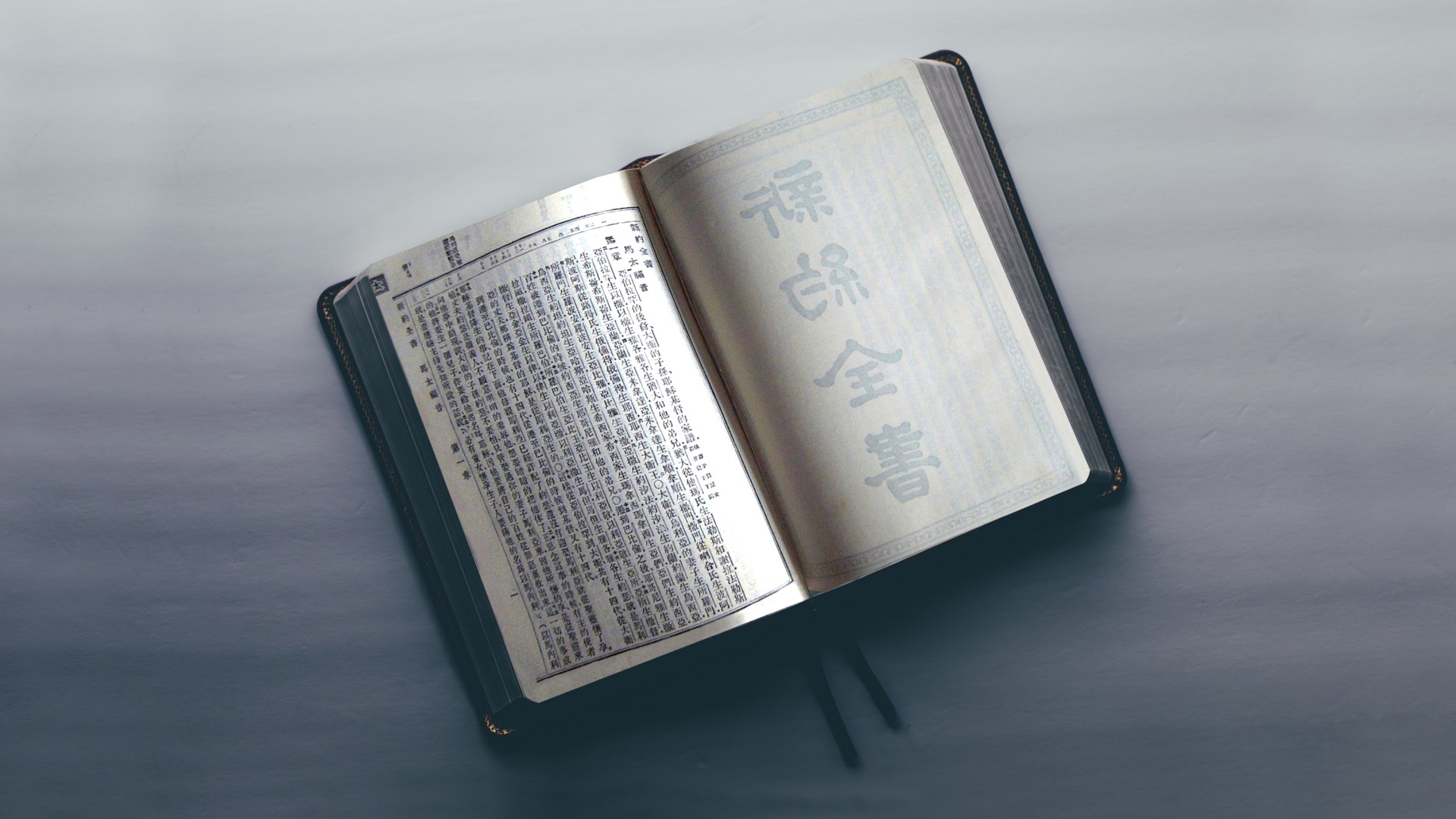

Since its publication in 1919, the Chinese Union Version (CUV) of the Bible has become the most dominant and popular translation in Chinese. Despite numerous changes to the Chinese language and a significant increase of new translations, its dominance is unabated and unshaken.

“It could well be the most influential ‘Chinese text’ among the Chinese readers for the past one hundred years and also in the future,” Taiwan-based scholar Chin Ken-pa wrote in the anthology Ever Since God Spoke Chinese. “Undoubtedly, even if we cannot claim it has become a ‘canon’ in the Chinese world, it is certainly an ‘authority.’”

The translation team of CUV included 16 Western missionaries and a few Chinese Christian experts, including Americans Calvin Wilson Mateer and Chauncey Goodrich; Englishmen George Sidney Owen and Frederick William Baller, and Chinese scholars Cheng Jingyi, Liu Dacheng, and Wang Zhixin. The translation of the Mandarin New Testament started in 1872, and the whole Bible was published in 1919. The guiding principles of translation included that it must be in the national language (not local vernacular), simple enough to be understood by people from all walks of life, and faithful to the original text without losing the rhythm of the Chinese language.

The translation of the Scriptures is essential to Christian tradition, as the missiologists Lamin Sanneh and Andrew Walls argue. Bible translation into Chinese has been crucial to the development of Christianity in China. Since the beginning of Protestant missions in China, Bible translation has been a major part of mission work.

For most Chinese Protestants, the CUV unquestionably remains an authority with the status of “God’s Word.” While there are multiple Chinese versions of the Scriptures, occasionally Chinese Christians declare on the internet that only the CUV is the true Bible, and all other versions are erroneous and even heretical (although it is now very rare to hear Chinese pastors and church leaders teaching “the inerrancy of CUV”).

Indeed, how fast the CUV rose to dominance and how enduring its dominance has turned out to be are truly mind-boggling phenomena. How can we explain this? As a historian of Chinese Christianity, I would like to highlight the following factors:

1. The CUV played a pivotal role in providing and shaping the theological vocabulary of the Chinese Protestant Church.

In their long and painstaking process of translating the Scriptures into Chinese in the early 19th century, Western and Chinese translators accumulated a rich repository of theological notions and terms in Chinese languages. The CUV inherited and integrated them into its language.

The CUV came out as Western missionaries’ dominance came to an end and the Chinese church came of age. Chinese Christians began to share leadership responsibilities and initiate indigenous evangelical revivals that swept across the country. This was the formative time for indigenous Protestant theological understanding and tradition.

The timely arrival of the CUV provided the Chinese Protestant community with a ready-made set of theological notions and vocabulary that Chinese believers immediately received and embraced. It did not take long for the CUV’s translation of such key biblical terms as faith, sin, salvation, and grace to become the standard “language of faith” used by church leaders, theologians, and evangelists as well as the average churchgoer on a daily basis.

The CUV’s translation of key biblical terms has been deeply ingrained in the theological DNA of the Chinese Protestant community around the world. It is fair to say that this is the only theological language system known and used unquestionably by this community up to today. In contrast, one can hardly identify any single, vernacular translation of the Bible which has had such a commanding and lasting impact on church life in the West.

2. The CUV helped shape a universally, unifying identity for Chinese Protestant communities around the globe.

Before the CUV, previous Chinese translations of the Scriptures had been done in either classical Chinese—only understandable to the educated elites in Chinese society—or in particular dialects for certain parts of the country. Therefore, the CUV’s aim to produce a translation understandable to all people from all parts of the country and all social classes turned out to be hugely strategic. It has served to unite all Chinese Protestant believers under one single Chinese version of the Scriptures.

Today, when you worship with any Chinese congregation in mainland China or the Chinese diaspora, you can easily feel the presence of a common, universal, Chinese Protestant tradition cemented by a shared set of spiritual vocabulary, classical hymns, and common version of the Bible, despite very different contexts. The CUV plays a big part in the forging and maintaining of this common identity among Chinese Protestant believers worldwide.

3. The CUV accompanied the Chinese church through its trials and suffering.

The past 100 years have been a turbulent time for the Protestant church in China. It endured numerous wars, revolutions, constant pressure from an atheist regime, and finally all-out persecution during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). Many Chinese believers would attest to finding comfort and strength in the CUV. They greatly loved to read and even memorize texts from handwritten copies of the CUV during the darkest years of the Cultural Revolution. The CUV is part of the Chinese church’s collective memory and heritage attesting to its perseverance and cross-bearing under tremendous suffering. There is a strong emotional bond between the CUV and the Chinese Protestant community that will not easily fade away.

4. The CUV’s exquisite rendering of the biblical texts gives it a special quality and lingering charm.

Linguistically speaking, the CUV does have its own advantage in the contemporary context. It is largely based on the vernacular of northern China but integrates some elements of classical Chinese. This combination reflects the genius of the original translating team. It makes the CUV understandable to ordinary folks but also appealing to the educated segments of society.

Having classical Chinese elements sometimes does make certain wordings read awkwardly or seem old-fashioned today. However, in reality, the CUV’s combination of the vernacular and classical may play to its advantage. Many Chinese believers, especially the more educated ones, would say they prefer the CUV over other more colloquial translations of the Scriptures precisely because a special charm comes with its unique style.

5. The CUV contributed to the emergence of the modern Chinese national language and the New Culture Movement and still commands significant respect within the greater Chinese society.

The longevity of the CUV’s popularity also has to do with its influence beyond the church. Since the late 19th century, China’s modernization project has gradually led to the transformation of a traditional dynasty into a modern nation-state. As part of this nation-building process, attempts were made to replace the single written language (classical Chinese) and diverse dialects with one single, unified, written and spoken language for the entire nation.

The breakthrough came in the form of the May Fourth New Culture Movement of the early 20th century, right around the time the CUV was published. The Bible emerged as one of the very few texts that met the goal of a vernacular, Mandarin-based, unified national language and immediately won popular endorsement.

As both Christian and non-Christian scholars agree, the CUV is a masterpiece of the modern Chinese language. It has served as an example for the May Fourth New Culture Movement and also benefited from the movement’s successful, rapid popularization of the new vernacular based upon the Chinese national language.

The CUV’s contribution in this regard is still widely recognized today by Chinese academia. Scholar George Kam Wah Mak even claims in Ever Since God Spoke Chinese that “as John the Baptist paved the way for Jesus, these vernacular Mandarin translators of the Bible are the pioneers in making vernacular Mandarin a national language.” Not surprisingly, the CUV’s role in China’s nation-building is compared to the roles of Bible translation in nation-building in modern Europe (as scholar Liu Lixia explains in the same book).

Additionally, the CUV is the most cited Bible translation when the biblical terms and texts are quoted by secular academia today. In other words, the CUV enjoys de facto status of being the scholarly norm in China.

In conclusion, the reasons behind the enduring popularity of the CUV among Chinese Protestants and in society run deep historically and presently. For most Chinese believers, the CUV is much more than just another Chinese translation of the Scriptures; it is very close to their hearts. That is why, with all the criticism of the CUV’s “antiquity” and “inaccuracy,” there is virtually no sign that its dominance will change in the foreseeable future.

We can ask whether it is theologically correct to equate the CUV with the Word of God, and whether some Chinese believers have a tendency to turn the CUV into an idol. However, the reality is if any viable revision of the CUV has a chance to win popular acceptance, it has to keep the CUV’s original texts intact as much as possible and make as few changes as possible.

The CUV is a precious gift to the Chinese church from God and has been used by him to nurture generations of believers. How much longer is God going to use the CUV for his glory in China? God alone knows.

Kevin Xiyi Yao is associate professor of world Christianity and Asian studies at Gordon Conwell Theological Seminary.

Originally published by ChinaSource.