Did you know Russia attacked a Ukrainian nuclear power facility, and “a government official said that elevated levels of radiation were detected near the plant”? Did you hear about the Ukrainian soldiers trapped on a tiny island who told off a Russian warship before they died defending their post? Or did you see the video of the “Ghost of Kyiv,” the ace Ukrainian pilot shooting down Russian bombers midair?

You may think you know these stories, but you don’t. And neither do I, because each is half-true at best. Russian forces did attack the power plant, but early reports of a radiation spike, like the CBS tweet I quoted above, were false. The International Atomic Energy Agency had said as much before CBS posted, yet, weeks later, CBS hasn’t deleted its erroneous tweet as of the time of writing this. The warship story isn’t quite true, either: Ukrainians did insult the ship, but they weren’t soldiers, and they aren’t dead. As for the Ghost of Kyiv, that one’s a total whopper. The footage came from a video game.

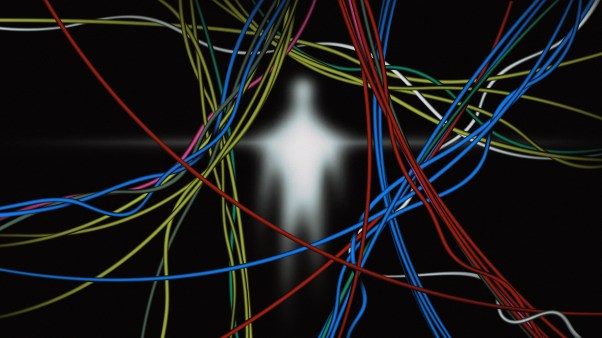

Beyond the brutality of the physical battlefield, the conflict in Ukraine is an information war. And unlike bombs and tanks thousands of miles away, that battle is all around us. Watching the conflict in real time, we’re all targets for misinformation.

Fact checks help, sure. But sometimes even generally credible news sources like CBS leave up errors, and sometimes even the fact checks are fake. If we want to avoid becoming casualties in the information war, what we need most is not endless debunking of every false tweet, but to build intellectual virtues.

“God enjoins us in Scripture to pursue” these virtues, writes Wheaton College emeritus philosopher W. Jay Wood in Epistemology: Becoming Intellectually Virtuous. The command is not only for professional philosophers: “The Bible is unequivocally clear that Christians are to superintend the life of the mind. ‘Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds’ (Rom. 12:3). God cares about how you think, not just what you think. … No walk of life is without the need for insight, discretion and love of truth.”

Intellectual virtue concerns “your very character, the kind of person you are and are becoming,” Wood says. “Careful oversight of our intellectual lives is imperative if we are to think well, and thinking well is an indispensable ingredient in living well.”

That was always true, but the sheer volume of information to which we can now expose ourselves daily has made it more pressing. The global theater of information warfare tied to the conflict in Ukraine means our need for intellectual virtue is at present especially acute. Wood wrote more than two decades ago, but his suggestion of three key virtues—studiousness, intellectual honesty, and wisdom—is just as needful now.

Studiousness means seeking truth well, steering between the excesses of vicious curiosity on the one hand and credulousness and oblivion on the other. A studious person values learning the truth, but she’s also attentive to how she learns it (some research methods are unethical), what she does with it (knowledge may be abused), and whether there are other, better things to which she should attend instead (Did you really need to know about that tweet? Will having that knowledge help anything or anyone?).

Studiousness is also a matter of attitude and self-discipline. A studious person “must not be quarrelsome but must be kind to everyone, able to teach, not resentful” (2 Tim. 2:24). They should be intellectually generous, diligent, and aware of their own limitations. “The one who has knowledge uses words with restraint, and whoever has understanding is even-tempered” (Prov. 17:27), so sometimes to be studious requires us to keep silent.

Intellectual honesty concerns how we respond to knowledge while acquiring it. It’s the virtuous mean between intellectual dishonesty and willful naiveté, and it requires us to deal in sincerity and good faith, even when we can’t expect the same from others (Rom. 12:17–21).

The intellectually honest person scrutinizes his own thinking and is scrupulous about admitting when he’s wrong, working to “put off falsehood and speak truthfully to [his] neighbor” (Eph. 4:25). He is on the lookout for motivated reasoning in himself and others, asking whether he believes something merely because he wants it to be true. And someone who is intellectually honest will never dissemble, or “call evil good and good evil” (Isa. 5:20), though that may be the easy or popular course of action.

Last, wisdom is the virtue we need to put knowledge we’ve sought and gained to good use. The wise person’s life will be “marked by deep and abiding meaningfulness, anchored in beliefs and purposes that offer lasting contentment,” Wood says. This person wants knowledge of “ultimate significance—knowledge that explains the most important features of our world, especially as they bear on human happiness.”

This requires circumspection and prudence, a healthy skepticism that doesn’t devolve into cynicism and—particularly in our information age—careful curation of one’s own attention. Wisdom requires rejecting belligerence, pedantry, pride, and rumormongering, all of which are encouraged in much of our traditional and social media.

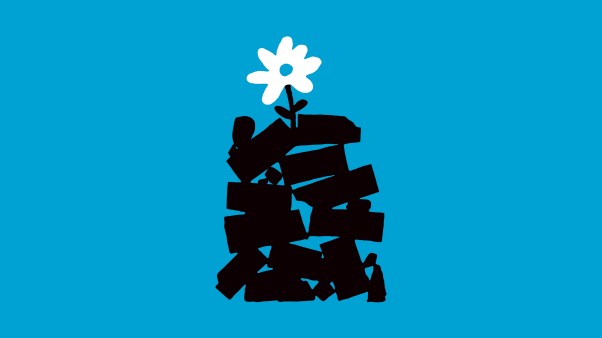

I can’t end this column with five short steps to becoming intellectually virtuous. Virtues need time, practice, and patience to take root; the most I can offer here is a seed. Nor can I conclude with some foolproof guide to recognizing propaganda online. The scale and nature of this war—where your answer to a question as basic as who’s winning may depend on where you live—mean any concrete recommendations I could give would rapidly become useless. The power of modern, decentralized propaganda is how quickly it can evolve.

But we can log off more often. Touch grass. Pray more than we post. We can remember that the fate of Ukraine doesn’t depend on whether you share another article. As C. S. Lewis wrote in a letter in 1946, that it is not “the duty of any private person to fix his mind on ills which he cannot help,” and “the mere state of being worried is [not] in itself meritorious. … We must, if it so happens, give our lives for others; but even while we’re doing it, I think we’re meant to enjoy Our Lord and, in Him, our friends, our food, our sleep, our jokes, and the birds song and the frosty sunrise.”

Developing intellectual virtues is not a task to which we’re left on our own. Woods reminds us, “We can “hardly do better than to recall the words of James: ‘If any of you lack wisdom, ask God, who gives to all generously and ungrudgingly, and it will be given you’ (Jas 1:5).” In information warfare, as ever, “God is ready to assist us.”