The mark of a theological giant, some say, is the ability to capture the imagination of readers far removed from their own historical period, cultural context, and, importantly, theological tradition.

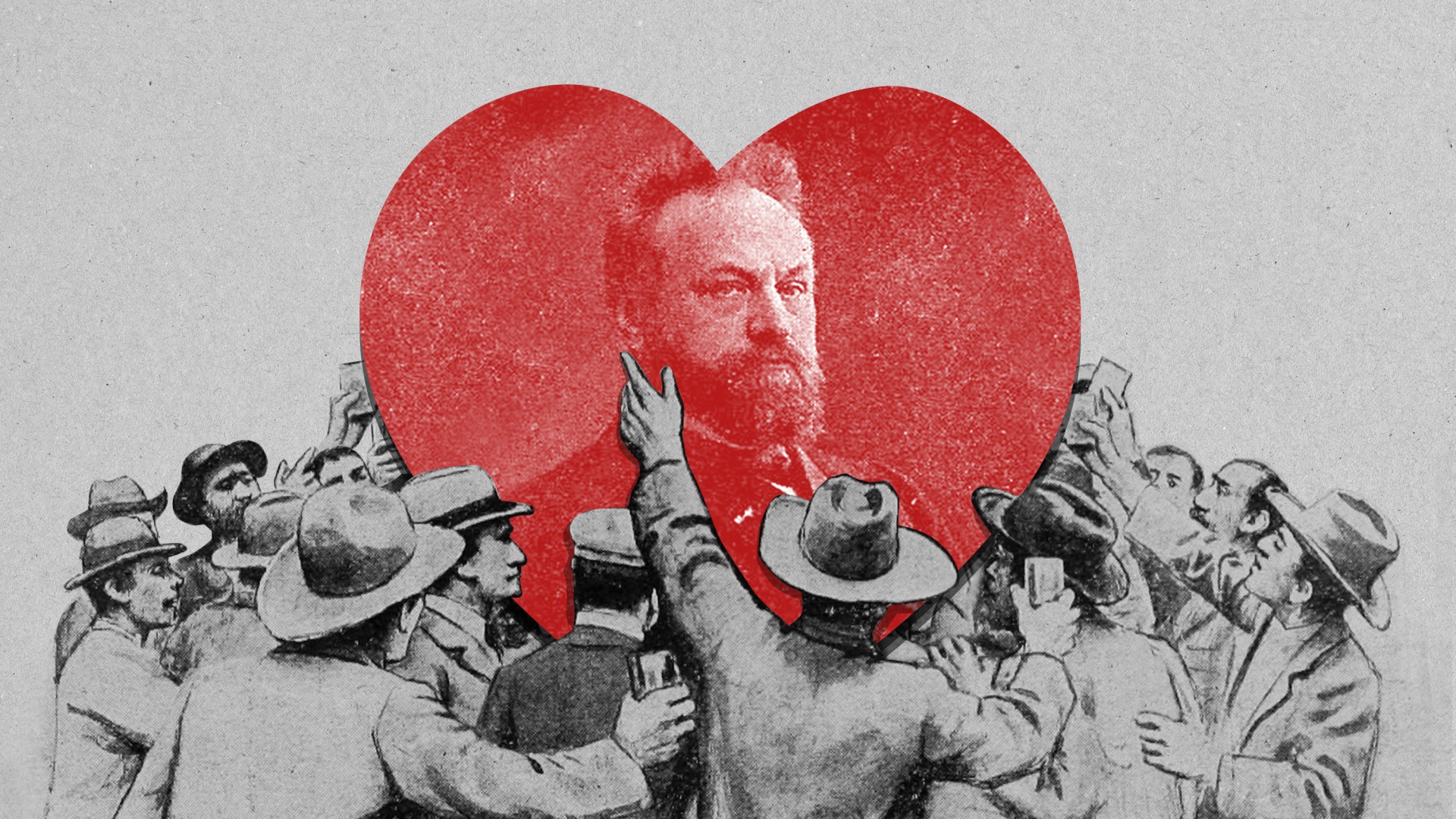

In the history of Christianity, the list of figures who enjoy that kind of reach is small—and doesn’t grow in a hurry. Over the last decade or so, however, a new star is rising in the firmament: the Dutch neo-Calvinist theologian Herman Bavinck (1854–1921).

In the Netherlands in his own day, Bavinck was a household name. The finest Dutch theological mind of his generation, Bavinck was also a notable public figure at a time of tremendous social upheaval—leaving his mark on the fields of politics, education, women’s rights, and journalism. Across the country, streets and schools were named after him. Beyond this, Bavinck was notable as a person of international standing. On a trip to the United States in 1908, for example, he was hosted at the White House by Theodore Roosevelt. Such honors say a lot.

Despite this, Bavinck’s legacy at home gradually fell into obscurity in the decades after his death. Overseas, his reputation as a stellar thinker lingered amongst those with Dutch connections but failed to grow beyond that over the course of the 20th century. All of that changed in the early years of the 21st century—thanks to the efforts of John Bolt and John Vriend, whose English translation of Bavinck’s Reformed Dogmatics was released in four parts between 2003 and 2008.

To date, those volumes have sold over 90,000 copies—a staggering output for a work of its nature. And that is to say nothing of the Portuguese or Korean versions, or the Spanish, Russian, and Chinese translations which are currently underway.

But to fast-forward from the release of Bavinck’s Dogmatics in English to his wide present-day popularity and simply say “The rest is history,” would be wrong. To do so would overlook the important question of why this figure became the go-to theologian for so many today—from Beijing to São Paulo, New York to Seoul. How did Herman Bavinck gain such a diverse global audience?

Every day in my own line of work—teaching Reformed theology at the University of Edinburgh—I interact with and hear from people who are wrestling with Bavinck’s work. Very few of those are Dutch or have any prior sense of loyalty to (or longstanding awareness of) the neo-Calvinist tradition. In fact, they are from all over the global church. Why has Bavinck’s work gained a greater degree of crossover traction than so many of his Reformed peers?

The reasons for this are no doubt as complex and diverse as the kinds of people who now read him: Korean Presbyterians will likely have different reasons than Southern Baptist readers, or than the Pentecostal teenager who devours Bavinck’s Wonderful Works of God as devotional material. Others, like the great Swiss theologian Karl Barth, rely on Bavinck as a guide to the history of theology. In light of these various motivations, I would not attempt to offer any kind of reductionistic answer to the question, “Why Bavinck in 2022?”

That said, I have been reading his works for nearly 15 years—alongside people from different parts of the world, and from Christian traditions and settings that vary from the strictly academic to the personal and churchly. In that time, I have observed certain traits in Bavinck’s writing and life that seem to draw a crowd time and time again—and that, crucially, keep those readers coming back. While these may not be the only reasons for Bavinck’s apparent sudden popularity, they are nonetheless significant.

First, Bavinck wrote in a balanced way that stands out for 21st century readers. We are accustomed to theology being done as a poor show of polemics conditioned by the norms of social media—unnuanced and uncharitable, bloated on a diet of low-hanging fruit, captive to its cartoonish portraits of the historical greats, and shot through with bad faith assumptions about those with whom we disagree today.

In that setting, Bavinck’s writings are a breath of fresh air. Erudite and capacious, he offers readers a vista of the breadth and depth of the Christian tradition, often with spectacular clarity. Although his work was (quite intentionally) styled as theology in the Reformed tradition, it was never narrowly sectarian in character. Rather, it was Reformed as an expression of something bigger: the catholic Christian faith, which takes root across cultures and centuries. Bavinck held together the paradox of being resolutely Calvinist, while also publicly affirming that, “Calvinism is not the only truth.”

That kind of balance shows a faith conviction that is both firm and supple, inviting conversation partners even from outside his own camp in a way that rebarbative, sharply polemical theologians simply do not. Its openness invites Christians from other traditions to explore Bavinck’s Reformed perspective.

Bavinck modeled the Christian worldview as an inductive, lifelong pursuit of godly wisdom—one that was open and inquisitive, rather than closed and rigid. In that regard, his approach was different from his famous colleague Abraham Kuyper, for whom the Christian worldview was deductive and inflexible.

Bavinck’s reluctance to fight straw men (and alongside that, his commitment to befriend his ideological opponents in person) is part of the same package. To be sure, he certainly was not a perfect interpreter of every theologian or tradition covered in his Dogmatics. Nonetheless, his strenuous effort to understand and faithfully represent those with whom he disagreed over the course of his life is striking.

Inexperienced readers of his Dogmatics may occasionally find themselves confused to find Bavinck take seemingly contradictory doctrinal stances at various points throughout the work. Yet in reality, those surprised readers are likely encountering Bavinck’s critique of a particular viewpoint—one that he presented at length on its strongest terms before giving his own verdict. Such a trait is subtly but strongly attractive to readers outside his own theological camp because it takes opposing perspectives seriously.

It is easy to dismiss criticism from someone who misrepresents or misunderstands your view, but it is far more difficult when that person has made a serious effort to present your view accurately and charitably. In fact, for those who wish to grow as thinkers, that kind of critique is attractive, not repellent. It wins trust.

Bavinck’s life story also plays an important role in his growing recognition in our contemporary era. We live in the wake of a 20th century bifurcation between fundamentalism and the social gospel. Those who were raised on either side of that debate have been given a strange inheritance: on the right, a gospel that speaks powerfully into the needs of one’s soul but offers little good news for society’s improvement in a fallen world; and on the left, a commitment to addressing social wrongs but in the context of a woefully-thin spiritual framework.

By contrast, Bavinck provides us with a startling reminder that this bifurcation is both a historical novelty and an unnatural distortion of a holistic and historic Christianity.

What did this look like in Bavinck’s own life? Alongside his resolutely orthodox theology, he was a noted critic of racism in America. His South African student Bennie Keet became a prominent anti-apartheid activist. In the Netherlands, Bavinck campaigned publicly against urban poverty (even calling for changes to housing standards and taxation laws to that end), stood against the oppression of poor factory workers (on account of their status as divine-image bearers), and strove for equal education for girls and the right to vote for women.

In our day, Bavinck stands out because of his commitment to the orthodox faith and the social consequences of that faith. In that sense, he goes against the grain of our late 20th century instincts in the same way as the likes of John Stott and Tim Keller. Such figures feel properly out of place on both the left and the right. As a theologian with a sweeping view of historic Christianity, Bavinck reminds us that our generation is out of step with the faith of the ages.

Bavinck was not a perfect man or a flawless theologian (as I tried to portray in Bavinck: A Critical Biography). But in his life and doctrine, he was a profoundly credible Christian—and as such, he is someone to whom so many are still drawn today.

Truth be told, I can think of many great theologians, past and present, whom I would probably rather meet in print rather than in person. That is not so with Bavinck. I will be reading him for some time yet, and suspect I am not the only one.

James Eglinton (@DrJamesEglinton) is Meldrum Senior Lecturer in Reformed Theology at the University of Edinburgh. He is the author of Bavinck: A Critical Biography (Baker, 2020), which won The Gospel Coalition 2020 Book of the Year for History and Biography, and was a finalist for the ECPA Christian Book Award in 2021.