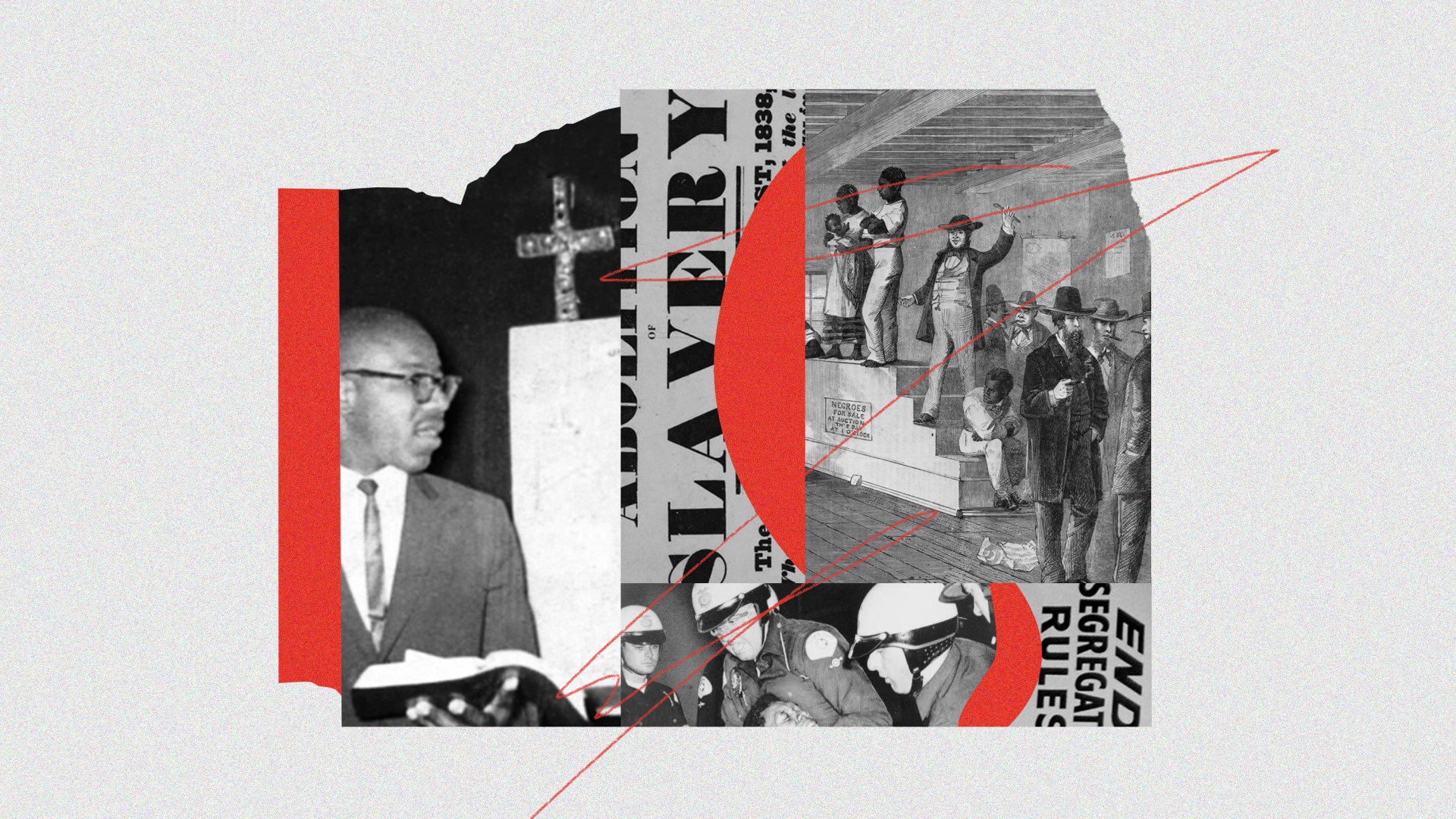

John Perkins stood up at a planning meeting for a Billy Graham crusade in Jackson, Mississippi, in 1975.

The Black pastor and civil rights activist was invited to the meeting, along with a group of African American clergy from the area, because Graham himself had insisted the evangelistic event would be desegregated. Black and white Mississippians would hear the gospel together. Perkins loved Graham and his powerful gospel message, and he was excited to hear that the world’s leading evangelist was taking practical steps to end segregation in the church.

So he went to the Holiday Inn in Jackson and sat down on the Black side of the conference room, with all the Black pastors, and looked over at the white side, with all the white pastors.

Then he stood up.

He asked the white pastors whether their churches were committed to accepting new converts from the crusade into their congregations if the born-again brothers and sisters were Black.

He didn’t think they were ready for that in Mississippi. And if they weren’t ready, he didn’t know whether he was either.

“I don’t know whether or not I want to participate,” Perkins said, “in making the same kind of white Christians that we’ve had in the past.”

He was thinking of all the white Christians who had closed the doors of their churches to Black people. And the white Christians who had supported the Mississippi Plan to stop Black people from voting so they could, as one state legislator described it at the time, “establish white supremacy in the State, within the limits imposed by the Federal Constitution.”

He was thinking of the white Christians whose only response to racist violence perpetrated on Black bodies was to say, “Wait.” And the white Christians who not only had not been moved by the injustice of Jim Crow to join the civil rights protests but also had seen Black churches in their own towns obliterated—burned and bombed—and never said a thing.

And he may also have been thinking of Jonathan Edwards.

Opponents of abortion on demand had hoped the U.S. Supreme Court would rule in favor of an Illinois statute that restricts abortion. But in a decision early last month, all nine justices refused—on procedural grounds—to decide the case. The Court’s action has the effect of upholding an appeals court ruling against the law.The Illinois statute required doctors to provide information about abortion procedures and the unborn child to women seeking abortions. Doctors were required as well to use techniques most likely to preserve the life of a fetus that might survive an abortion.The law initially was challenged in federal district court by doctors who perform abortions. The court ruled that parts of the law that would impose criminal penalties on physicians were unconstitutional, in light of the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion. An appeals court later affirmed the district court ruling against the Illinois law.A prolife physician named Eugene F. Diamond then appealed the case, known as Diamond v. Charles, to the Supreme Court. The state of Illinois, whose law was at stake, did not enter an appeal, but merely filed a “letter of interest” in the case. The Supreme Court refused to rule on the case, saying Diamond, acting on his own, did not have sufficient legal standing to appeal the case.The high court concluded that Diamond could not prove he had any direct stake in the case, even though he disagrees with the practice of abortion. “The presence of a disagreement, however sharp and acrimonious it may be, is insufficient by itself,” the Court said, to seek a resolution in the federal court system. The Supreme Court holds that persons seeking federal court action must show they suffered some actual or threatened injury in the matter that is being appealed.Douglas Johnson, of the National Right to Life Committee, said the ruling “should not discourage future efforts to defend state laws” restricting abortion. However, Johnson said, it is essential that state officials be party to those cases.WORLD SCENEIRELANDA Referendum on DivorceVoters in the Republic of Ireland could decide as early as this month whether to lift a constitutional ban on divorce.The government announced last month it would introduce legislation to hold a referendum on the divorce ban. The 1937 constitutional provision can be changed only by a majority of the popular vote in a referendum.Opinion polls indicate as many as 77 percent of the Irish population favor allowing divorce “in certain circumstances.” However, the same polls show only a narrow majority willing to vote for the complete removal of the constitutional prohibition.If the ban is removed, the government says divorce would be allowed only in cases where a marriage can be shown to have failed and the failure has continued for a period of five years. The Roman Catholic Church, which claims 90 percent of the Irish population, opposes divorce. However, Ireland’s bishops are divided over how actively they should oppose efforts to lift the constitutional ban.HUNGARYChurches Help Drug AddictsSeveral churches in Hungary are launching drug rehabilitation programs with the government’s permission. Hungarian Christians say the efforts are contributing to the relaxation of tensions between church and state in the communist country.Baptists in Budapest have established a coffee house that seeks to minister to people with drug and alcohol dependencies. They are also setting up a rehabilitation center about 125 miles from the city. Pentecostal churches are opening a rehabilitation center just outside Budapest. And the Free Christian Church Council is planning to establish treatment facilities.These developments gained impetus from meetings conducted last year by American evangelist Nicky Cruz. A former drug addict and New York City gang leader, Cruz visited Hungary at the invitation of Hungarian churches.The nation’s communist government earlier had asked the churches to help combat the growing problem of drug and alcohol dependency among young people.More than 5,000 people heard Cruz speak at two evangelistic meetings. In addition, physicians and church leaders from five East European nations attended a seminar on drug addiction led by Cruz.The evangelist stressed the spiritual component in rehabilitation, saying, “Only after they have truly received Christ and are born again will they begin to consider the way they talk, the way they dress, the company they keep, the places they go, the things they do.”LATIN AMERICAOpposing WEF MembershipMeeting in Venezuela, delegates to a general assembly of the Confraternity of Evangelicals in Latin America (CONELA) voted against joining the World Evangelical Fellowship (WEF).CONELA’s executive committee had recommended that the Latin American group join WEF. But a delegation from Mexico led an effort against the proposal, saying WEF needs to make itself better known among Latin American church leaders. While voting against WEF membership, the assembly did accept an invitation to send observers to WEF functions.After the vote, a CONELA official said most evangelical church leaders in Latin America object to the practices and policies of the World Council of Churches. As a result, he said, they view with suspicion any unknown international and interdenominational agency.In other action, delegates to the CONELA general assembly approved a declaration that calling it “another gospel [that offers] temporary liberation from physical problems such as poverty and certain political dictatorships.” The declaration calls for renewed evangelism across Latin America and asks both leftist and rightist governments to respect the “personal rights” of individuals.Delegates elected Virgilio Zapata, general secretary of the Evangelical Alliance of Guatemala, as CONELA’s new president. Outgoing president Marcelino Ortiz of Mexico will continue to serve on the organization’s executive committee. Formed four years ago in Panama, CONELA includes 206 denominations and Christian service agencies.ROMECompetition from ‘Sects’The Vatican has released a report recommending changes in Catholic parish life to help stem the loss of members to other religious groups. Chief Vatican spokesman Joaquin Navarro Valls says competition from non-Catholic groups is “one of the major dangers facing the church.”The 27-page document, titled “Sects or New Religious Movements: A Pastoral Challenge,” says sects have flourished because of “needs and aspirations which are seemingly not being met in the mainline churches.” Non-Catholic religious movements succeed because they provide “human warmth, care and support in small close-knit communities … [and] a style of prayer and preaching closer to the cultural traits and aspirations of the people.“The challenge of the new religious movements is to stimulate our own renewal for a greater pastoral efficiency,” the report states. The document cites “deficiencies and inadequacies in the actual behavior of the church which can facilitate the success of sects.” And it calls on the Catholic church to consider changes, including the creation of “more fraternal” church structures that are “more adapted to people’s life situations.… Preaching, worship and community prayer should not necessarily be confined to traditional places of worship.”The document drew from information contained in questionnaires completed by some 75 bishops’ conferences around the world. Luis Eduardo Castano, ecumenical officer for the Latin American Catholic Bishops’ Conference, said the church is concerned about the growth of fundamentalist and charismatic Protestant groups in Latin America.

Opponents of abortion on demand had hoped the U.S. Supreme Court would rule in favor of an Illinois statute that restricts abortion. But in a decision early last month, all nine justices refused—on procedural grounds—to decide the case. The Court’s action has the effect of upholding an appeals court ruling against the law.The Illinois statute required doctors to provide information about abortion procedures and the unborn child to women seeking abortions. Doctors were required as well to use techniques most likely to preserve the life of a fetus that might survive an abortion.The law initially was challenged in federal district court by doctors who perform abortions. The court ruled that parts of the law that would impose criminal penalties on physicians were unconstitutional, in light of the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion. An appeals court later affirmed the district court ruling against the Illinois law.A prolife physician named Eugene F. Diamond then appealed the case, known as Diamond v. Charles, to the Supreme Court. The state of Illinois, whose law was at stake, did not enter an appeal, but merely filed a “letter of interest” in the case. The Supreme Court refused to rule on the case, saying Diamond, acting on his own, did not have sufficient legal standing to appeal the case.The high court concluded that Diamond could not prove he had any direct stake in the case, even though he disagrees with the practice of abortion. “The presence of a disagreement, however sharp and acrimonious it may be, is insufficient by itself,” the Court said, to seek a resolution in the federal court system. The Supreme Court holds that persons seeking federal court action must show they suffered some actual or threatened injury in the matter that is being appealed.Douglas Johnson, of the National Right to Life Committee, said the ruling “should not discourage future efforts to defend state laws” restricting abortion. However, Johnson said, it is essential that state officials be party to those cases.WORLD SCENEIRELANDA Referendum on DivorceVoters in the Republic of Ireland could decide as early as this month whether to lift a constitutional ban on divorce.The government announced last month it would introduce legislation to hold a referendum on the divorce ban. The 1937 constitutional provision can be changed only by a majority of the popular vote in a referendum.Opinion polls indicate as many as 77 percent of the Irish population favor allowing divorce “in certain circumstances.” However, the same polls show only a narrow majority willing to vote for the complete removal of the constitutional prohibition.If the ban is removed, the government says divorce would be allowed only in cases where a marriage can be shown to have failed and the failure has continued for a period of five years. The Roman Catholic Church, which claims 90 percent of the Irish population, opposes divorce. However, Ireland’s bishops are divided over how actively they should oppose efforts to lift the constitutional ban.HUNGARYChurches Help Drug AddictsSeveral churches in Hungary are launching drug rehabilitation programs with the government’s permission. Hungarian Christians say the efforts are contributing to the relaxation of tensions between church and state in the communist country.Baptists in Budapest have established a coffee house that seeks to minister to people with drug and alcohol dependencies. They are also setting up a rehabilitation center about 125 miles from the city. Pentecostal churches are opening a rehabilitation center just outside Budapest. And the Free Christian Church Council is planning to establish treatment facilities.These developments gained impetus from meetings conducted last year by American evangelist Nicky Cruz. A former drug addict and New York City gang leader, Cruz visited Hungary at the invitation of Hungarian churches.The nation’s communist government earlier had asked the churches to help combat the growing problem of drug and alcohol dependency among young people.More than 5,000 people heard Cruz speak at two evangelistic meetings. In addition, physicians and church leaders from five East European nations attended a seminar on drug addiction led by Cruz.The evangelist stressed the spiritual component in rehabilitation, saying, “Only after they have truly received Christ and are born again will they begin to consider the way they talk, the way they dress, the company they keep, the places they go, the things they do.”LATIN AMERICAOpposing WEF MembershipMeeting in Venezuela, delegates to a general assembly of the Confraternity of Evangelicals in Latin America (CONELA) voted against joining the World Evangelical Fellowship (WEF).CONELA’s executive committee had recommended that the Latin American group join WEF. But a delegation from Mexico led an effort against the proposal, saying WEF needs to make itself better known among Latin American church leaders. While voting against WEF membership, the assembly did accept an invitation to send observers to WEF functions.After the vote, a CONELA official said most evangelical church leaders in Latin America object to the practices and policies of the World Council of Churches. As a result, he said, they view with suspicion any unknown international and interdenominational agency.In other action, delegates to the CONELA general assembly approved a declaration that calling it “another gospel [that offers] temporary liberation from physical problems such as poverty and certain political dictatorships.” The declaration calls for renewed evangelism across Latin America and asks both leftist and rightist governments to respect the “personal rights” of individuals.Delegates elected Virgilio Zapata, general secretary of the Evangelical Alliance of Guatemala, as CONELA’s new president. Outgoing president Marcelino Ortiz of Mexico will continue to serve on the organization’s executive committee. Formed four years ago in Panama, CONELA includes 206 denominations and Christian service agencies.ROMECompetition from ‘Sects’The Vatican has released a report recommending changes in Catholic parish life to help stem the loss of members to other religious groups. Chief Vatican spokesman Joaquin Navarro Valls says competition from non-Catholic groups is “one of the major dangers facing the church.”The 27-page document, titled “Sects or New Religious Movements: A Pastoral Challenge,” says sects have flourished because of “needs and aspirations which are seemingly not being met in the mainline churches.” Non-Catholic religious movements succeed because they provide “human warmth, care and support in small close-knit communities … [and] a style of prayer and preaching closer to the cultural traits and aspirations of the people.“The challenge of the new religious movements is to stimulate our own renewal for a greater pastoral efficiency,” the report states. The document cites “deficiencies and inadequacies in the actual behavior of the church which can facilitate the success of sects.” And it calls on the Catholic church to consider changes, including the creation of “more fraternal” church structures that are “more adapted to people’s life situations.… Preaching, worship and community prayer should not necessarily be confined to traditional places of worship.”The document drew from information contained in questionnaires completed by some 75 bishops’ conferences around the world. Luis Eduardo Castano, ecumenical officer for the Latin American Catholic Bishops’ Conference, said the church is concerned about the growth of fundamentalist and charismatic Protestant groups in Latin America.Shaking Christians and convicting sinners

Edwards, of course, was a Puritan theologian and pastor in New England who had died more than 200 years before. He had a marked influence on American revivalists, from Charles Finney to Billy Graham. And he deeply shaped a number of notable 20th-century preachers, including John MacArthur and John Piper, who once said that Edwards’s writings were, for him, “more Christ-exalting, more God-revering, more Bible-illuminating, more righteousness-beckoning, more prayer-sweetening, more missions-advancing, and more love-deepening than any other author outside the Bible.”

For most of American history, Edwards was known specifically for his role in the Great Awakening. He preached an incredible sermon about hell and spiders that spurred on the fire of revival.

The sermon was so iconic, so central to what revivalistic-minded Christians in America meant when they said “revival,” that Billy Graham once preached the same sermon. In Los Angeles in 1949, Graham told his audience he was going to do something a little different and instead of preaching his own words, he was going to preach Jonathan Edwards’s.

“It’s not too long,” he said. “I’m going to read it, and extemporize part of it, but I want you to feel the grip, I want you to feel the language. I’m asking tonight the same blessed Holy Ghost that moved in that day to move again tonight in 1949 and shake us out of our lethargy as Christians and convict sinners that we might come to repentance.”

Perkins probably didn’t know that, though he was in LA at the time. He had fled to California from Mississippi two years before, after a white sheriff’s deputy killed his brother. But Perkins had not yet accepted the gospel and come to Jesus.

It wasn’t until 1957 that Perkins went to a Sunday school class with his son and heard and accepted the truth that he was loved by God. Then he went and studied how to be a preacher with John MacArthur’s father, Jack, and returned to Mississippi to start a ministry with the same name as Jack MacArthur’s radio program: Voice of Calvary Ministries.

So Perkins probably didn’t know that Graham had once preached “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.”

He probably also didn’t know that Edwards defended slavery and himself purchased two Black children in his life—a 14-year-old girl and a 3-year-old boy. Edwards’s argument for owning humans with a different skin color wasn’t published.

Buying humans

Edwards’s biographers briefly mentioned slaves and slavery but didn’t go into the details about how the minister had, at 27, personally driven more than 130 miles to pay 80 pounds for a 14-year-old girl who was named Venus by the men who stole her from Africa. When he returned home, the girl’s body, her work, and all her future children and their bodies and their work belonged to him by law. He had the receipt in his pocket that said she was his to “Use and behoof”—make use of—“for Ever.”

Nor did the biographers mention how, at 52, Edwards bought another human, a toddler named Titus. He paid 30 pounds for the three-year-old. When the boy was five, Edwards included him in his will, in a list of animals that he owned.

But if Perkins didn’t know about the famed preacher’s personal relationship to slavery or private defense of the practice, he did know that nothing in Edwards’s great sermon about sin had convinced anyone in Mississippi that slavery, race-based segregation, or white supremacy was wrong.

He knew the white Christians could embrace revivalist Christianity, from Edwards to Graham, without ever questioning the injustice that was visited on the Black people around them.

He knew that some white Christians in Mississippi even named their children Jonathan Edwards. And some of those children grew up to be violent racists.

Perkins knew one of them himself. So when he stood up in the evangelistic planning meeting and said “I don’t know whether or not I want to participate in making the same kind of white Christians that we’ve had in the past,” he may well have been thinking of that Jonathan Edwards.

The other Jonathan Edwards

That other Edwards—Jonathan R. Edwards—was elected sheriff of Rankin County in 1962. One of the things he mentioned to voters in his campaign, besides his six years as a deputy and his deep roots in the community, was that he was a lifelong Baptist.

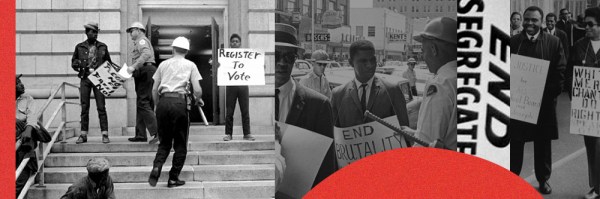

The month after he took office, Edwards was called to the Rankin County courthouse because three Black men were attempting to register to vote. At the time, there were 6,944 African Americans in Rankin County, but only 43 of them could vote. If these men registered, that would make it 46.

But Edwards and his deputies made sure that didn’t happen. The sheriff walked up to one of the men and hit him.

“I hit him and kept on hitting him,” Edwards later testified in court. “And if he hadn’t run I would have kept on hitting him.”

The Black man, who may have been trained by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, did not meet the sheriff’s violence with violence. That didn’t stop Edwards from hitting him more.

“I slapped him down the first time,” Edwards said. “I knocked him down and he fell here and I got in on him, and I don’t know how many times I hit him, just as many as I could.”

The judge in the case ruled that Edwards hadn’t violated the man’s civil rights. He said the sheriff wasn’t attempting to keep anyone from voting and it was “purely incidental” that the beating happened in the registrar’s office.

Besides, the judge concluded, this was a “past event” and “there was no reasonable justification to believe that such an incident would ever occur again.”

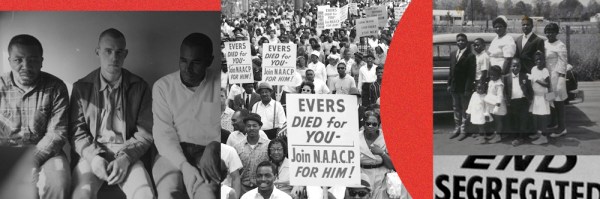

It did happen again. That time, the sheriff with the name of the great American preacher assaulted John Perkins.

In 1970, Perkins led more than 100 demonstrators in a march protesting segregated businesses in Mississippi. They chanted, “Do right, white man, do right.” On their way home from the march, 20 college students were arrested and taken to the Rankin County jail. Fearing the students might be lynched, Perkins and two other boycott leaders rushed to bail them out.

They found the sheriff’s deputies drinking corn whiskey. The deputies had forcibly shaved the heads of two protestors and were pouring the liquor over their raw scalps.

When Edwards saw Perkins coming into the jail, he recognized him as the leader. He said, “This is the smart n—.” Then he started beating him.

He hit Perkins, possibly with a blackjack, a weapon made out of wood and lead wrapped in leather. Perkins went down and Edwards kicked him, brutally and repeatedly, stopping only to retuck in his shirt.

When the beating was finished, the sheriff made the minister get up and mop his own blood off the floor.

Edwards later testified that Perkins had thrown an unprovoked punch at him but missed. No one else saw it. Perkins also had a pistol in his car, though he hadn’t brought it in with him and the sheriff didn’t know about it until after the arrest when he went and searched the car.

Edwards told the court, nevertheless, that the violence was justified.

“Sure they were roughed up,” he said, “but they asked for it.”

What the gospel can do

Perkins almost died from his injuries. In the hospital, he thought a lot about the racism that had put him there. He thought about white people—white Christians—who would name their son Jonathan Edwards and have him grow up to be a racist sheriff.

“I came to the conclusion, the hard conclusion,” Perkins later said, “that Mississippi white folks were cruel. And they were unjust. And the system was totally bankrupt. … I stayed with the idea that it had to be overthrown.”

As a Christian, Perkins believed the gospel could overthrow that system. God could reconcile sinners to himself and each other. Jesus could take hate from human hearts and replace it with love. The Holy Spirit could move people to give up power instead of defending it with violence.

Perkins would preach and protest and risk injury again because he believed in the power of the gospel.

It couldn’t be a gospel, though, that produced more Jonathan Edwardses.

Which is why he stood up in 1975 and asked the people planning a Billy Graham crusade a question that still resonates in America today: Will the gospel you are preaching produce a different kind of white Christian than it has in the past?