Not long ago, a friend at our church lost her husband of fifty-plus years unexpectedly during the pandemic. She was not allowed to be by his bedside as he passed away in the hospital, and she could not hold a proper funeral for him. She returned alone to the empty house that she had recently bought with him, boxes still packed up from the move. The warmth and promise of a cozy retirement home had frosted over with the chill of a tomb.

Home is more than a physical building—it is a place of permanent belonging, often shared with those we love. Jesus, knowing that his death is near, promises his disciples that he is going ahead to prepare a place for them in his Father’s house (John 14:2–4). Why, I have often wondered, does he promise this in particular?

Perhaps one answer is that his promise draws out an important theme for his disciples, who were part of a people whose narrative identity was marked by periods of exile and sojourning. The disciples may not have been desert wanderers like their forefathers, but they had left everything to follow the One who had no place to lay his head. The promise of an eternal home must have resonated deeply with them.

Today, as Jesus’ disciples, his promise resonates with us too. In the season of Lent and all through the year, in a myriad of ways we also yearn for the miraculous movement from wilderness to safety, exile to belonging, sojourning to home.

One way this longing has been expressed by the church is through the liturgical calendar. Over the centuries, the church has appropriately linked Lent with the desert, the epitome of exile. For example, the collect for the first Sunday of Lent in The Book of Common Prayer focuses on Christ’s desert temptations, and the daily office readings for the season are saturated with passages from Exodus, Deuteronomy, Jeremiah, and the latter half of Genesis, pointing to the Israelites’ long history of sojourning and later uprooting. In this season, churches all over the world are meditating on what it means to point our feet homeward.

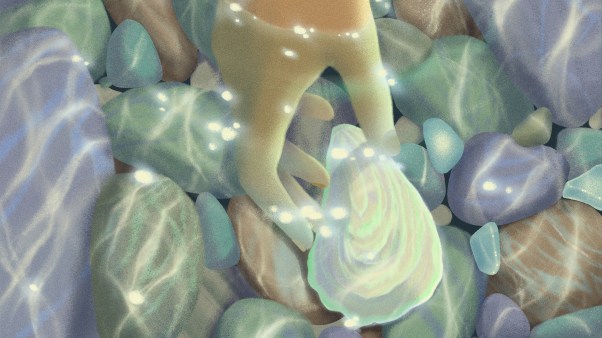

In my own life, the longing for home was imprinted on me from birth. My mother immigrated to the US from South Korea with my father in the 1980s, carrying only what could fit inside her suitcase. She left everything behind—her parents, personal aspirations, the ability to communicate, all that is familiar—and spent most of her days alone in a small apartment, losing hope and clumps of hair to debilitating depression. I was born not long after. Each year on my birthday when I have miyeok-guk (seaweed soup) in honor of my mother, as the Korean people have done for centuries, I think of how the taste evokes tears.

On the other hand, my husband’s family has lived for over a hundred years on the same eight-thousand-acre farm in the Oklahoma panhandle. In the house built by my husband’s grandparents, the quilts stitched by the hands of great-great-great-grandmothers, pieced together from old dresses and work shirts, gently warm our sleeping children at night, the sixth and precious generation.

My husband and I and our children live in Michigan, however, and we make it to the farm once a year at best. Each year the groundwater levels dip lower, another storefront in town goes empty, and more of the property turns into sand. It is heart-wrenching to realize we could become the last generations to have memories of this place. Even here, where permanence once seemed so sure, the loss of home finds us.

I suspect that each one of us, in our own ways, knows what it means to lose our sense of home and to long for a time and place when we were safe in our belonging. Sometimes our homes are taken from us physically, as when a hurricane tears through the backyard, war comes to the doorstep, or a thief breaks in. Sometimes we can be sitting in our very own living rooms and feel a devastating loss, as when abuse threatens our safety, a family member passes away, or a rift widens between ourselves and a loved one. Even our spiritual homes—our churches, small groups, and ministries—can be taken from us to leave us abandoned and alone. Even if we somehow manage to never experience losses like these, the reality is that on this side of heaven, we are all exiles in the face of death. In the end, we all must leave our earthly home.

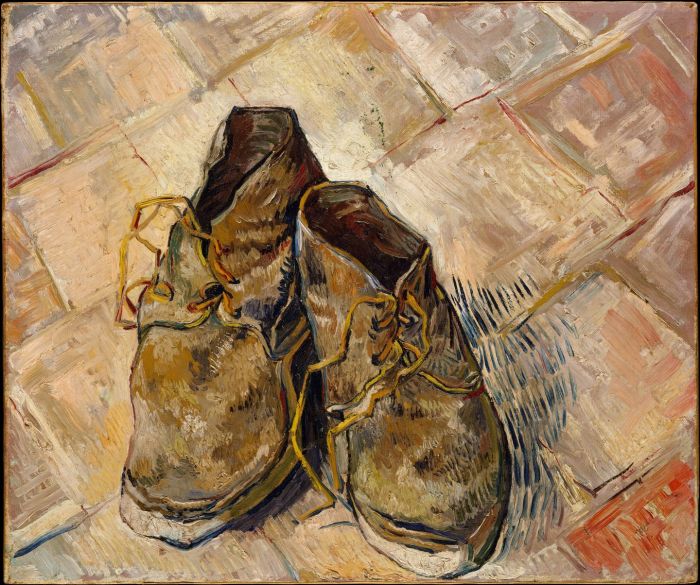

Vincent Van Gogh / Wikimedia Commons

Vincent Van Gogh / Wikimedia CommonsIf death is the ultimate exile, Easter is the ultimate promise of homegoing. For though it is true we are a people familiar with homesickness, we are also a people among whom God dwells. Just as the wandering Israelites had the presence of God to go with them, we also have a risen Savior who says, “I will be with you always.”

Recently my widowed friend has started something she calls Monday Manna. From the depths of her sorrow, she has emerged to put on a pot of soup, bake a loaf of bread, and invite friends over each week as an act of gratitude. Her face glows over the pages of the worn Bible as she reads to us and prays, her smile an expression born from ashes. To eat at her table is to glimpse a time when death and tears and exile will be no more. Even now, the stone is slowly rolling and the angel is hovering over the tomb.

The pioneer forefathers of my husband’s family lashed the clock to the wagon and plodded off in search of something better, as did my own parents. They thirsted for the milk and honey that come with the desert sand, and they swallowed it all with resolute hearts. Now the sixth generation has come to visit, running across the prairie and startling the grasshoppers, and a late summer rain paints the fields green for another day. Meanwhile, my parents—the lonely immigrant couple—find a church where they commit their lives to Christ beside friends who become like family. In joining their lives to Jesus, they become the means through which many others become a part of Christ’s family over the years—including me. The story continues.

No eye has seen and no ear has heard, but we can guess that our Eastered home with Jesus will taste something like a bowl of my mother’s miyeok-guk and feel like an old quilt pulled close. It will be like seeing the beloved squint-eyed grandfathers standing at the plow once more, turning to embrace us. It will be like sitting around a table with laughing, cherished people, like watching a smile bloom on the widow’s face. It will be like coming home.

“Blessed are those whose strength is in you, in whose heart are the highways to Zion,” sing the sons of Korah in Psalm 84 (ESV). “As they go through the Valley of Baca, they make it a place of springs.” Easter means that our longings for home are not aimless and fruitless. Our hearts are paved with the way to our Father’s house. Like the Israelites, like the disciples, like all who come before us, we have only to keep walking. And as we walk we find that Christ, who walks beside us, makes our footsteps to water the earth.

Sara Kyoungah White serves as the senior editor on staff with the Lausanne Movement. She lives in Grand Rapids, Michigan, with her family.

This article is part of New Life Rising which features articles and Bible study sessions reflecting on the meaning of Jesus’ death and resurrection. Learn more about this special issue that can be used during Lent, the Easter season, or any time of year at http://orderct.com/lent.