Wycliffe Bible Translators has become renowned as the world’s leading Bible translation organization, and William Cameron Townsend is well known for his role as its founder. Yet this is only half of the story. Townsend also founded the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) which has played an important part in Wycliffe’s success. SIL—known today as SIL International—is a scientific as well as a faith-based organization. The story behind SIL’s rise and of Kenneth L. Pike, the key character in that rise, is one of the most interesting episodes of the modern missionary movement.

Townsend and the birth of a vision

In 1917, Townsend arrived in Guatemala as a Bible salesman. The standard practice of selling Spanish Bibles to the Kaqchikel, K’iche’, Mam, and other indigenous peoples who spoke little or no Spanish proved frustrating. Townsend later recalled that Guatemala’s indigenous inhabitants kept asking, if not in these exact words, something like: “If your God is so powerful, why doesn’t he speak my language?” Staggered by the implications of this question, Townsend blazed a new path in missions.

Against the advice of veteran missionaries, the independent-minded Townsend translated the New Testament into Kaqchikel, completing it in 1930. He also started a school that used the indigenous language to train native pastors. From these experiences flowed Townsend’s threefold vision that would form the core of SIL.

Firstly, the move away from Spanish language ministry to Kaqchikel ministry and translation strengthened and expanded the indigenous church. Townsend found that Bible translation into the mother tongue was not optional but imperative if indigenous peoples were to understand its message and form viable indigenous churches.

Secondly, Townsend discovered that unwritten indigenous languages were not simple or primitive but rather extremely complex and capable of expressing the full range of human thought and emotion. Faced with an enormously complex grammatical structure, he concluded that the recently developed science of structural linguistics held the key to cracking the mysteries of these languages. He therefore sought out the advice of Edward Sapir, a leading linguist at Yale University. By enlisting scientific research in support of Bible translation, Townsend was on the path to creating an entirely different kind of mission.

Thirdly, living in close contact with Guatemala’s indigenous communities, he became acutely aware of these peoples’ extreme poverty and powerlessness due to illiteracy and social marginalization. For Townsend, saving souls was not enough. A true Christian response included social uplift. He was convinced that community development was an essential component of Christian missions.

For an evangelical missionary in the 1930s, the embrace of Bible translation was fitting, but science and social concern were hardly the stuff of evangelical missions. In the wake of the modernists-fundamentalists controversies, intellectual pursuits and the life of the mind—not to mention social ministry—were in serious decline in conservative evangelical circles. After all, it was from within the academy that evolution and secularism were emanating. In order to pursue the three strands of ministry he envisioned, Townsend was compelled by circumstance to found his own organization, hence the Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Townsend first set his sights on anti-clerical and revolutionary Mexico. Since the country was closed to traditional missionaries when he crossed the border in 1933, he resourcefully dropped his missionary identity and entered Mexico as an ethnologist and educator. Clearly, even at this early date, he envisioned creating something other than the standard evangelical faith mission. During his two-month, 5,000-mile survey trip, Townsend met a number of key figures, of which the most important was Mexico’s director of rural education, Rafael Ramírez, who opened the way for him to study the nation’s educational system.

Mexico sorely needed linguistic research to develop the country’s many unwritten indigenous languages before real educational gains could be made. Mexico’s revolutionary leaders also remained frustrated in their efforts to raise the indigenous population out of grinding poverty. Townsend was bold to the point of audacity. Despite having no money or workers, he proposed to Mexican officials a “three point program of Bible translation,” cooperation in “scientific research,” and assisting “the government in its welfare program” on behalf of the indigenous peoples.

Townsend was a great salesman, and he convinced Mexican education officials that SIL could make a legitimate scientific and humanitarian contribution. They were even ready to permit Bible translation in order to gain the linguistic and community development aid promised by this intrepid American. SIL would be like no other mission. Motivated by religious purpose, it was yet truly scientific and pursued humanitarian aims. “In fifteen years,” Townsend exclaimed, “we will make the scientists sit up and take notice.”

Townsend envisioned sending young evangelicals into Mexico with his newly formed Summer Institute of Linguistics. Once there, they would carry out linguistic research and publish the results in academic journals. They would also develop alphabets, produce grammars and dictionaries for unwritten languages, translate the New Testament, and undertake community development and educational projects. It was a tall order, one that would require a new kind of specially trained missionary: the translator-linguist.

Pike and the realization of the vision

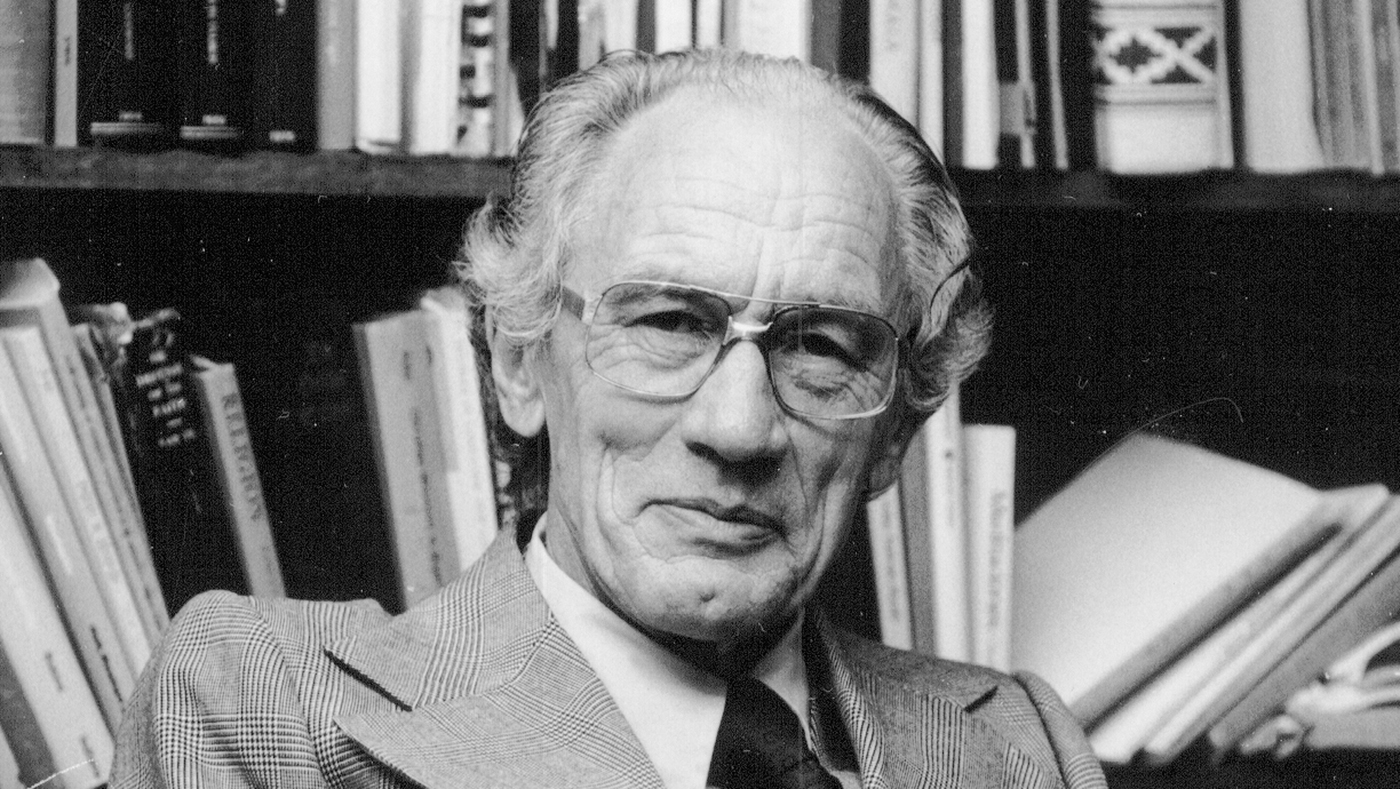

In 1934, Townsend established a summer linguistic course in rural Arkansas for training these translator-linguists. The first summer course was inauspicious. Only two students turned up for classes at the abandoned farmhouse Townsend rented for housing the “school.” The next summer Kenneth Pike, a skinny young man recently rejected by the China Inland Mission (CIM), arrived for the summer course along with four other students. The CIM had rebuffed Pike because of his nervousness and inability to pronounce Chinese. After failing as a CIM candidate, Pike had returned to Gordon College where he took a graduate course in Greek, and it was there that he learned of Townsend’s summer school. If he couldn’t be a traditional missionary, perhaps he could be a Bible translator? As unpromising as Pike appeared, Townsend had just collected his first linguistic genius.

In Mexico, with a mere ten days of phonetic training under his belt, Pike proved he had the makings of a competent linguistic scientist. He progressed rapidly in his analysis of the Mixtec language, into which he would translate the New Testament with the help of Angel Merecias. He quickly grasped the importance of the linguistic sciences for both the translation and humanitarian aims of SIL. In 1937, Pike wrote his family that “Townsend has his plan of action here in Mexico upon the basis of scientific research. In the bargain we will of course plan to do the translating which is our goal. But we do not want to masquerade as linguists and be anything else but that. The only answer is to become linguists, in fact, not theory, and deliver the real goods.”

Townsend took note of Pike’s ability and in 1937 sent him to the University of Michigan, where each summer the Linguistic Society of America held a “Linguistic Institute.” Leonard Bloomfield and Edward Sapir, the two leading linguists of the day, were present at the Linguistic Institute in 1937, and Sapir was impressed with Pike’s initial analysis of Mixtec.

Pike returned to the Linguistic Institute in 1938. After lecturing on his Mixtec linguistic analysis, he was offered an opportunity to pursue doctoral studies at the University of Michigan. After completing his doctorate in 1942, Pike joined the faculty at the university where he eventually became a tenured professor and remained until his retirement as professor emeritus in 1977. Pike also developed his own linguistic theory, tagmemics, which was used to analyze many previously unwritten languages. In the end, he would contribute more than 20 books and 200 articles to the academic literature. It is a little-known fact among American Christians that Pike was not only an evangelical missionary and Bible translator but also one of the world’s top linguistic scientists of the 20th century.

Providence smiled on Townsend. In 1936, another linguistic prodigy walked through the door. Eugene Nida, who had studied Greek and linguistics at UCLA, was a student for only a few weeks before Townsend placed him on the summer school faculty. Nida was SIL’s second PhD, graduating from the University of Michigan in 1943. For various reasons, Nida would move to the American Bible Society full-time in 1953, where he would become well known for developing the Bible translation theory of dynamic equivalence. In the first two decades of SIL’s existence, these two men were largely responsible for advancing the organization in a truly scholarly and academic direction.

SIL grew apace and by 1941 numbered nearly a hundred members serving in Mexico. Although Townsend had convinced Mexican officials of SIL’s standing as a bona fide scientific institution, as a college dropout he had only a hazy idea of what was required to fulfill this. By the early 1940s, Pike and Nida knew that some heavy lifting was required if SIL expected to keep up with the increasingly sophisticated and complex discipline of linguistics.

When the opportunity to partner with the University of Oklahoma at Norman in 1942 arose, the two men rightly saw it as a way to upgrade SIL’s academic credentials. SIL’s linguistic courses, taught by SIL personnel, became part of the university’s accredited curriculum. This cooperative program placed incredible strain on SIL at a time when evangelicals tended to disassociate from secular academia. Moreover, as Pike himself was well aware, American evangelicals were not exactly noted for scientific prowess. Indeed, they often prioritized the heart over the mind.

Both the SIL faculty and evangelical students struggled with the university setting, and Pike and Nida were forced to defend the program. An especially contentious point was the dropping of classroom prayer to accommodate the secular university setting. However, by the late 1940s, it was becoming evident that the academic merits of the cooperative program outweighed any perceived spiritual costs. Indeed, SIL members found that they could rub shoulders with non-Christians in academia without losing or harming their faith.

The growth of SIL led to another landmark event that took place in 1942—the founding of Wycliffe Bible Translators in the United States as a sending agency to resource the work that SIL was doing in the field. It would have been difficult for the scientifically oriented SIL to relate to the Christian public in North America. Hence the more religiously oriented Wycliffe was formed for this purpose. The dual structure was at times cause for accusations of duplicity, but the combination was effective in that it allowed each entity to focus on its own area of expertise.

From the time that Pike assumed the presidency of SIL in 1942, he labored to build SIL into a full-fledged scientific organization, while maintaining the founder’s threefold vision. In addition to producing a New Testament, each SIL translation project also conducted linguistic and anthropological research. By the early 1980s, the organization’s translator-linguists were laboring in 761 indigenous language projects and SIL members had published over 9,000 articles and books. Pike also groomed a growing cadre of professional linguists in SIL by encouraging the organization’s best minds to pursue doctoral degrees at top universities around the world. By the time he retired as president of SIL in 1979, the organization had more than 100 members with earned doctorates.

Had Ken Pike not happened upon the scene, it is most doubtful SIL would have attained such academic stature. Time and again, even in the highly academic SIL, Pike had to reassert the place of scholarship and its fundamental importance to producing good translations of the Bible when evangelistic activism threatened to usurp scholarly production and academic rigor. Evangelicals could, and should, he emphasized, serve God with their heart and mind. Scholarship, adding to the world’s knowledge, was a legitimate way to serve God. Pike modeled this throughout his career, self-identifying both as a missionary and a scholar until his death on December 31, 2000—all the while demonstrating that evangelicals could effectively serve God with both the heart and the mind.

SIL today

From its founding in 1934, SIL has grown from a small summer linguistics training program with two students to a diverse international staff of nearly 5,000. SIL has trained over 20,000 students in various aspects of linguistics, literacy, and other cross-cultural work through a network of training programs that now involves 26 institutions in 18 countries. Today SIL works alongside speakers of more than 1,600 languages in 100 countries, and more than two million people have learned to read and write as a direct result of SIL’s literacy efforts. SIL’s Language and Culture Archives houses over 60,000 works of various kinds, including scholarly publications, Bible translations, and vernacular literacy materials in addition to SIL’s flagship publication, the Ethnologue—an online database of the world’s more than 7,000 living languages.

SIL continues to play a key role in the global Bible translation movement. Not only does SIL directly facilitate Bible translation on a large scale, it also contributes through foundational research into the world’s languages and cultures, as well as through applied work in developing alphabets, dictionaries, local literatures, and programs of literacy instruction. Additionally, it serves the whole movement through foundational services—like consulting and software development—which support all these tasks.

When Townsend founded SIL to be a research organization, he saw it as an important strategy for getting beyond the gaps in knowledge that were hindering ministry. With an ever-changing world that does not cease to present new challenges, this strategy is just as relevant today as it was then. In response to this on-going need, SIL has recently established the Pike Center for Integrative Scholarship. Its mission, following the example set by Pike, is to build the capacity of the Bible translation movement to use scholarly research as a tool in meeting the challenges it faces. The heritage of Townsend and Pike is alive and well in the SIL of the 21st century.

Boone Aldridge (PhD, University of Stirling, 2012) is the SIL Corporate Historian; his book, The Development of the Wycliffe Bible Translators and the Summer Institute of Linguistics, 1934–1982, is in press with Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. Gary Simons (PhD, Cornell University, 1979) is SIL’s Chief Research Officer and director of the Pike Center for Integrative Scholarship. The authors have previously collaborated on an ebook that tells much of this story at greater length: A Threefold Purpose: Rediscovering the Heart of SIL.