Thomas Dorsey was 33 years old and had a flourishing career in secular music. In the previous 15 years, the Georgia native had moved to Chicago, completed his musical studies while picking up an endless number of side jobs, and eventually found a way to support himself and his expectant wife as a full-time musician. But it wasn’t to last. In the next months, Dorsey would lose his spouse and newborn son, a tragedy which spurred him to heed the advice of those closest to him. He would leave the secular music scene behind and fully dedicate his musical gifts to the church.

February 23, 155 (traditional date): Polycarp, the bishop of Smyrna, is martyred. Reportedly a disciple of the Apostle John, at age 86 he was taken to be burned at the stake. "You try to frighten me with fire that burns for an hour and forget the fire of hell that never burns out," he said. The flames, legend says, would not touch him, and when he was run through with a sword, his blood put the fire out (see issue 27: Persecution in the Early Church).

February 23, 303: Diocletian begins his "Great Persecution," issuing edicts that call for church buildings to be destroyed, sacred writings burned, Christians to lose civil rights, and clergy to be imprisoned and forced to sacrifice. The following year he went even further, ordering all people to sacrifice on pain of death (see issue 27: Persecution in the Early Church).

February 23, 1455 (traditional date): Johannes Gutenberg publishes the Bible, the first book ever printed on a press with movable type. (see issue 16: William Tyndale)

February 23, 1685: George Frederick Handel, composer of the oratorio "Messiah," is born. He died in 1759, having spent the last six years of his life in total blindness.

Over the next 60 years, Dorsey became known as the “Father of Gospel Music,” penning hundreds of songs and redefining the genre in beat, rhythm, and tempo. As The Voice reported, the Chicago musician dubbed his work “songs with a message.”

Nothing will take the place of gospel music. … Somebody might do it differently or add something to it, but any power in the music must come from God … and it’s all about what God wants.

The child entrepreneur

Thomas A. Dorsey was born in Villa Rica, Georgia, a small town outside of Atlanta, in 1899. He was the son of Thomas Madison Dorsey, a Morehouse College–educated, itinerant Baptist preacher, and Etta Plant, a Villa Rica native. When they married, Etta’s family was very influential in Villa Rica and owned a significant amount of land. But within a few years, the family lost their property, allegedly due to back taxes. Thomas’s father, a respected teacher and preacher, was forced to work as a sharecropper on the very land formerly owned by his wife’s family. Within a few years, the Dorseys moved to Atlanta in 1908, where both parents worked to help the financially struggling family survive.

The adjustment wasn’t easy for Thomas. He was placed a year behind his classmates in the Atlanta public school system and his peers often made fun of his speech and clothes. Thomas dropped out of school at the age of 10 and began working at a prominent black vaudeville theater, carrying water and doing other odd jobs. He reminisced about those early experiences in an interview with author Viv Broughton in her book Black Gospel: An Illustrated History of the Gospel Sound:

As a boy, I sold pop, ginger ale, and red rock at the 81 Theater, and I got a chance to meet all the stars … and they would want a pop or something, a cold drink on credit until payday, and I got a chance to know them all! I stayed ’round that theatre, I’d hang ‘round that theatre, and I learned a lot. I learned blues; I could play the piano, and I think it paid off very well for me.

As a young boy, Thomas had learned to play the piano from his mother, for whom music had been a significant part of her own family life. (Etta was an organist and her brother Phil was a well-known blues guitar player.) After the family moved to Atlanta, Thomas began walking 30 miles a week to take formal music lessons. As his musical ability improved, Thomas began playing for churches, house rent parties, bordellos, and women’s teas to help supplement his family’s income.

The Chicago challenge

In 1916, at the age of 17, Dorsey moved north to Chicago to pursue a musical career. Success was initially hard to come by. Dorsey soon learned he couldn’t earn union scale wages as a musician without a card, and he couldn’t obtain the card without a formal music education. (Musicians’ wages were paid according to a scale determined by their credentials with the professional Chicago union of musicians.)

To pay for his education, Dorsey worked days at a steel mill in Gary, Indiana, attended school at night, and established his own nightly rent-party circuit. (Rent parties were parties organized by tenants to pay for their rent.) In 1919, Dorsey completed his musical studies at the Chicago College of Composition and Arrangement and obtained his union card. Now he was free to play anywhere in Chicago and performed with various groups, including the Whispering Syncopators and a jazz orchestra.

Dorsey also joined Pilgrim Baptist Church. A preacher’s kid who had confessed faith in Christ as a child, he had also been influenced by his father’s flamboyant style, which he often imitated on the family porch in Villa Rica. But faith wasn’t a serious priority in Dorsey’s life until his early 20s, when he experienced a second conversion at a National Baptist Convention (NBC) in 1921. He related his experience to Steve Turner in his book An Illustrated History of Gospel:

There was a Baptist convention up the street from where I was staying. I was playing rags and blues at parties, and things on Saturday night. There was a fellow who came to the convention by the name of Nix who stayed with my uncle, and he got up one night and sang “I Know a Great Savior, I Do Don’t You?” After he finished, the minister said anyone could join the church. If you were interested, they would send you to a church of your choice. I thought, “Here’s my chance.” I was playing jazz music. In fact, I was working in clubs. So I quit. I walked off my job.

Initially, Dorsey’s conversion spurred him to end his secular music career, and he began playing for a storefront church. But the salary wasn’t enough to pay his bills. So, once again, Dorsey began to work in jazz and blues clubs. In 1924, Dorsey, with the Wild Cats Jazz Band, debuted with Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, at the Grand Theater in Chicago. Performing with Rainey was a significant career break for Dorsey: She was known as the “Mother of the Blues” and composed over 100 songs during the mid-1920s. Dorsey also scored and transcribed music for artists and singers, working closely with Mayo “Ink” Williams, who promoted music produced for a black audience by Paramount Studios.

Despite personal success, depression plagued Dorsey throughout his career. He appeared on stage one night with Ma Rainey and was unable to play. As biographer Michael Harris recounts in The Rise of Gospel Blues:

He said that he is playing at this club, and he tries to play some more and he can’t. I would say to him what happened? Were you paralyzed? numbness? He doesn’t remember any of these things, and he said, but I know my fingers—I know I could move my fingers. I just couldn’t play. Think of that. I have the muscular ability to move, but I can’t play. In other words, I can’t make music. I can’t create.

Some of those close to Dorsey, however, believed something else was at work. His wife and sister-in-law were unhappy that he had continued to pursue a secular musical career. Dorsey’s wife, Nettie, whom he married in 1925, believed that God had called him to write and sing gospel music and that the source of his inner turmoil stemmed from ignoring God’s calling.

Yet his secular career was rising. In 1928, Dorsey and guitarist Tampa Red released, “It’s Tight Like That”—a national sensation and a religious scandal. The song’s bawdy lyrics described lovemaking between a man and a woman. It was an instant success, selling over 500,000 copies. But pastors scoffed at a honky-tonk blues player trying to compose church music. They felt his music wasn’t suitable for dignified church worship.

Things began to change for Dorsey in the 1930s when influential NBC musicians began championing his music. A performance of Dorsey’s composition of “If You See My Savior” during a morning devotion left people “slain in the spirit.” Two NBC musicians gave Dorsey permission to set up a booth at the 1930 convention where he sold more than 4,000 copies of that song. For his part, Dorsey continued to play secular music while he visited churches and asked pastors to listen to his religious compositions.

A painful conversion

In 1932, Dorsey’s battle between secular and sacred reached a tragic resolution. The musician had gone to St. Louis to sing at a revival. During his trip, he received a telegram telling him to return home— his wife had just died in childbirth. His infant son died the next day.

Initially, Dorsey became angry and bitter with God after their deaths, believing that God had wronged him. In his grief, he refused to do anything for God; he only wanted to pursue his secular career. But God had something to say to him, as Dorsey later recounted in “The Precious Lord Story and Gospel Songs”:

You are not alone. I tried to speak to you before. It was you that should have gotten out of the car and not gone to St. Louis. … I said, Thank you, Lord, I understand. I’ll never make that same mistake again.

The following Saturday after Nettie’s death, Dorsey met up with his friend Theodore Frye. There, he later said, God gave him the words and melody for “Take My Hand, Precious Lord”:

Something happened to me there. I had a strange feeling inside … a calm—a quiet stillness. As my fingers began to manipulate over the keys, words began to fall in place on the melody like drops of water falling from the crevice of a rock.

The popularity of “Precious Lord” throughout the country helped revolutionize the worship atmosphere and later, inspired many in the civil rights movement. Frye introduced the song to Martin Luther King Sr.’s Ebenezer Church. On the day he died, Martin Luther King Jr. requested that “Precious Lord” play at a future event. The song later played during both Martin Luther King Jr. and Lyndon B. Johnson’s funerals.

Music as a Christian calling

Dorsey brought his own ideas to church music. He insisted that the purpose of his music wasn’t to tear down the traditional old-line churches but to dedicate his musical gifts to God, as The Rise of Gospel Blues quoted him:

I wasn’t trying to change it [church music], but I was just struck with something that would change it over, something that God gave me. He accepted it; I got my authority from God.

Dorsey dubbed his music “gospel blues” due to the similarity of his gospel rhythms and vocals to those heard in blues and jazz clubs. He employed the “call and response” pattern in his songs that also reminded pastors of songs composed and sung by their enslaved ancestors.

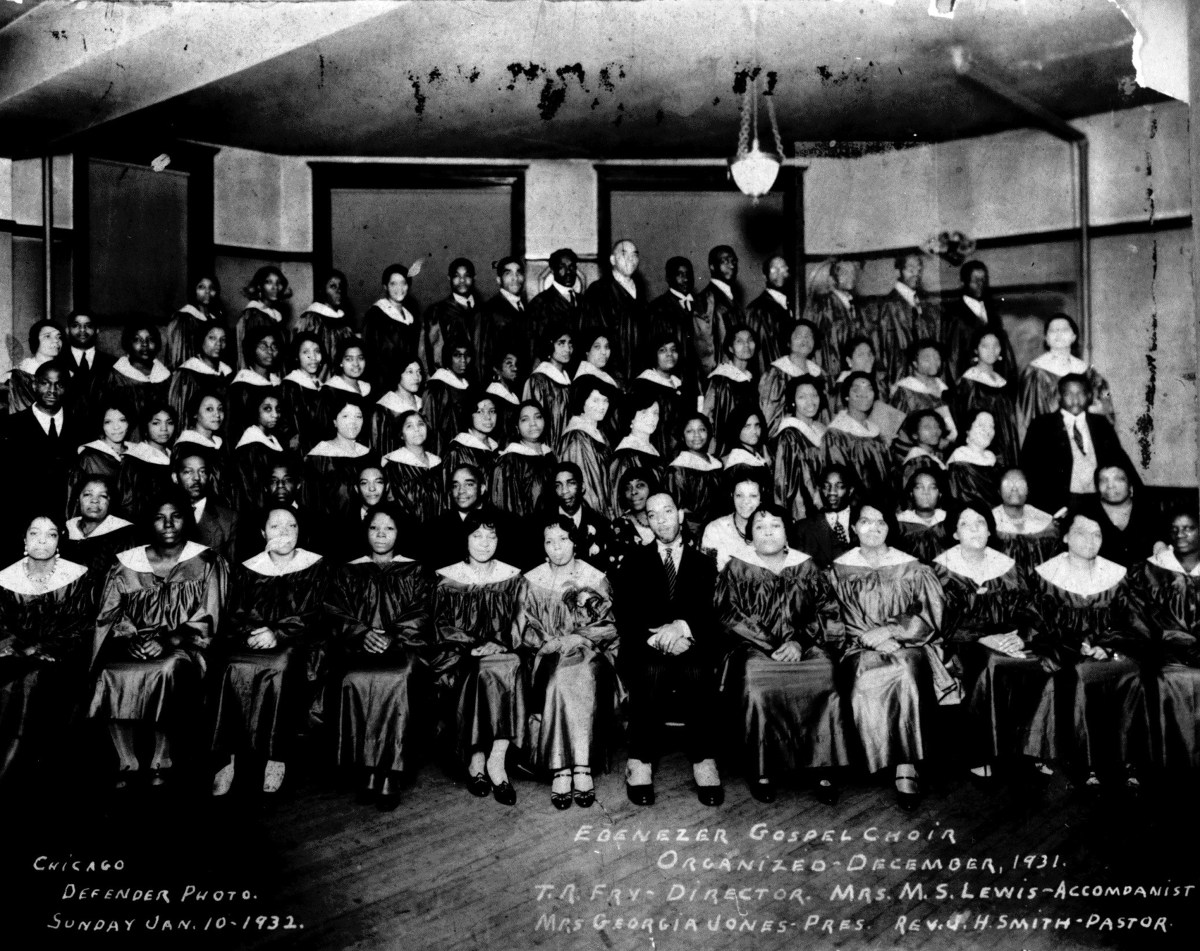

Eventually, Dorsey’s style of worship took hold. In 1931, the established “silk-stocking” Ebenezer Baptist Church organized a gospel choir, marking the beginning of gospel music’s acceptance by mainline churches. The energy from the Great Migration also impacted this social musical revolution. Blacks relocating to the North from the South wanted a type of singing that reminded them of home—songs with rhythm, hands clapping, and feet tapping.

Frustrated with the Northern worship style, newly arrived Southern blacks who had joined large churches left and began to join storefront churches where worship services resembled the ones they left in the South. Pastors at traditional churches began to take notice.

At Pilgrim Baptist, Dorsey’s own pastor was encouraged by the success of Ebenezer’s gospel choir, and he soon hired Dorsey to serve as the church’s gospel choir director and musician in 1932. Dorsey held that position for more than 50 years. Ebenezer and Pilgrim’s acceptance of gospel music as a religious genre helped to fuel gospel music’s prominence in church worship not only in Chicago but also across the country.

The same year that Dorsey decided to pursue gospel music full time, he and several fellow musicians organized a mass Chicago gospel music chorus. That original choir expanded into the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses (NCGCC), organized at Pilgrim Baptist Church in 1933. The NCGCC became the first organization for black gospel singers in the country.

Sallie Martin, one of Dorsey’s singers, became the first organizer of the convention, traveling around the country and adding choral unions and chapters to the organization. The NGCCC offered musicians and singers across the country a venue to hone their craft, learn from each other, and take back songs (affectionately known as Dorseys ) to teach to their own choirs.

In 1940, Dorsey married his second wife, Kathryn, who had specifically visited Pilgrim to “catch his eye.” Together, the couple had a son and a daughter. Kathryn proved to be a source of inspiration for her husband—her name is included on some of his song publications.

A gospel legacy

Thomas Dorsey published and performed his own music for decades. He earned his nickname as “The Father of Gospel Music” because of his impact on traditional gospel from the 1930s to 1950s. For most of his life, when he wasn’t playing or leading music in Chicago, Dorsey traveled around the United States demonstrating his music, conducting workshops, presiding over music conventions, and occasionally writing.

Since 1993, Dorsey’s hometown of Villa Rica has held a festival honoring his contributions to gospel, blues, and jazz. His former employer, Pilgrim Baptist also hosts an annual tribute to his legacy. Gospel music has become an established course in colleges around the country; one Christian college now offers a bachelor’s degree program in gospel music. The crowning testament to Dorsey’s legacy will be the proposed National Museum of Gospel Music, which is set to open on the site of the original Pilgrim Baptist Church building.

Dorsey always admitted that he didn’t coin or invent the term gospel music. Yet he revolutionized its sound and delivery. His songs had a beat, rhythm, and tempo and shared the Good News, as quoted by The Rise of Gospel Blues.

I took the word, took a group of singers, or one singer … and I embellished [gospel], made it beautiful, more noticeable, and more susceptible with runs and trills and moans in it. That’s really one of the reasons my folk called it gospel music.

Dorsey’s songs shared the message of God’s love and care for his people. They gave hope to people during the Depression and Jim Crow era. As he later reminisced in Salim Muwakkil Chicago Reader’s piece:

I kept pushing gospel because, somehow, I knew I was right. I knew I was the one the Master wanted to do it, and I did it. I was richly rewarded for my persistence. I’ve traveled and performed all over the world, and I’ve heard my songs sung in lots of different languages.

A prolific songwriter throughout his 93 years of life—Dorsey died in 1993—he nevertheless kept a soft spot for the hymn that catapulted his gospel career, calling it “the greatest song I have written out of near four hundred gospel songs.”

“The price exacted for ‘Precious Lord’ was very high,” he said at the age of 70, alluding to the loss of his first wife and son. “The grief, the sorrow, the loneliness, the loss, the uncertainty of the future, but I was requited or repaid with double dividends and compound interest.”

Kathryn B. Kemp is an associate minister at Memorial Baptist Church, member of the Pastoral Alliance of the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses and the academic faculty of the Gospel Music Workshop of America. Her music ministry spans more than 50 years of service. She has written two books on gospel music, and her book Sacred Song Survival: Salvation in the African American Religious Experience is due for publication later this year (Covenant Books).