What’s Going On?

Christianity in the regions now considered part of the Soviet Union has a long and glorious history, dating back even before 988. But it seems that an atheistic state like the USSR would disdain any mention of that history, much less a grand celebration of it. So what’s going on—and what’s wrong—with the big Soviet show?

It’s finally come. the observance that millions of Ukrainian, Byelorussian and Russian Christians have been waiting for, the millennium of the Christianization of Rus’. That is, the alleged 1,000th anniversary of the occasion when the Grand Prince Vladimir ordered the people of his kingdom to be baptized into the Orthodox Christian faith, and personally oversaw the baptisms of the majority of the people in Kiev, the capital of his realm.

But the arrival and celebration of this millennium is heavily laden with irony. Probably the chief irony is the fact that the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the Soviet Union, a zealously atheistic government, is endorsing—even funding and promoting—the most spectacular of the many events worldwide that are being dedicated to this “millennium of Christianity in Rus’.”

A second great irony is that the city of Kiev, where the celebrated baptism took place, is now the capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (UkSSR), one of the several republics in the the USSR. So we have the descendants of the people that Vladimir led into the fold of Christendom now under the rule of a Cornmunist government that, if it is to comply with the tenets of orthodox Marxist Leninism, must consider religion “an opiate of the people” and work in every possible way to discourage its existence.

So what’s really going on here, in this irony-filled celebration of the “Christianization of Rus”?

“Russian” Christianity’s Story

Actually, the message of Christ had reached the lands north of the Black Sea long before the 980s. Church tradition has it that sometime between 50 and 60 A.D. the Apostle Andrew, the first apostle that Jesus called, visited the future site of Kiev and possibly left new converts behind in other parts of that region, which was then known as Scythia. In fact, the Apostle Paul mentions the Scythians in his letter to the Colossians (3:11), apparently suggesting that some were already becoming Christians.

History tells us that late in the first century, the bishop of Rome, St. Clement, was exiled to Kherson (just south of the Rus’ region) and then martyred there. History also tells us that Christianity spread through the Greek colonies along the coast of the Black Sea, and that bishops from the Black Sea and Scythian regions attended some of the earliest ecumenical councils.

In the mid-900s, the Christian soldiers in the army of Prince Sviatoslav (Prince Vladimir’s father) said their vows of allegiance in a church building that had already been constructed in Kiev, the Church of the Prophet Elias. So obviously Christianity was far from unknown in those regions, though it was assuredly a minority religion, whose adherents were far outnumbered by worshippers of the Eastern Slavs’ pagan idols.

But then, in about 955, Princess Olga, the wife of Sviatoslav’s father and regent to her son, apparently went to Constantinople and was baptized an Orthodox Christian. Then Vladimir, her grandson, embraced Christianity, and proceeded to establish it as the state religion.

Radical changes in the culture soon followed. Vladimir abolished the death penalty. He and his successors established schools throughout the realm, so that the people could learn how to read the Scriptures. They established welfare institutions in order to take care of the unfortunate.

The road ahead looked bright. But in 1054 the Universal Church split into Eastern and Western. The Kiev metropolitanate, which was under the jurisdiction of the patriarch of Constantinople, remained in the Eastern Orthodox realm. Not long after, invaders from Asia destabilized the state to the extent that the Kiev metropolitan fled north to Vladimir-on-Kliazma, and later moved his seat to Moscow. Yet these metropolitans retained the Kiev title until the 15th century, when the Moscow Church declared itself to be autocephalous (that is, self-headed). Meanwhile, Constantinople re-established a metropolitanate in Kiev.

Turbulent times continued. The Kievan Church was again divided in 1596, when the majority of the bishops in Rus’ at the time accepted a reunion with the See of Rome, creating what came to be known as the Ukrainian Catholic Church (Eastern Rite). So the Orthodox patriarch of Constantinople consecrated a whole new set of hierarchy for the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (which became the name of choice for the region once called Rus’).

The Orthodox in Ukraine remained under the jurisdiction of the patriarch of Constantinople until 1686. At that time the Orthodox leaders in Moscow used political pressure to influence the Turks (who had been in control of Constantinople since 1453) to allow the transfer of the Kiev metropolitan to the jurisdiction of the Moscow Church.

Shortly thereafter, the ruler in Moscow, Peter I (r.1689–1725), began calling himself the “Tsar of all the Russes,” intending by such a title to suggest that all the people in his dominion, despite their varying ethnic origins, were fraternal peoples who had actually always longed to be united in a single state. Ukraine he called “Malaria”—Little Rus’; Byelorussia he called “Belaia”—White Rus’; and Russia he called “Velikaia”—Great Rus’. The term he coined for this union was “Rosiia” (taken from the Greek version of Rus’).

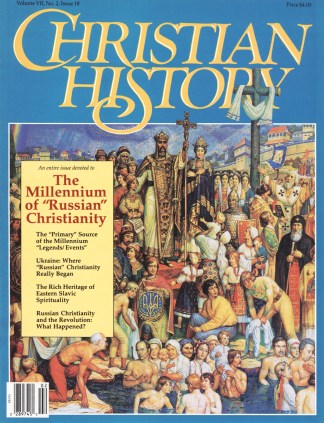

A popular subject for painting—some places: Paintings of the baptism of Kiev, like this modern rendering by S. Konarz Konashewych, are quite popular in the West. But in Soviet Ukraine, where the event actually took place, government repression keeps it much less popular—at least in public.

Peter proclaimed the Russian Orthodox Church the official church of all his empire, and effectively used the Church to help him strengthen his hold over all the “Russes.” He hoped, by incorporating these diverse peoples under one name, to build a massive, unified empire that would last forever. He and his heirs went on to conquer some Asian lands, and similarly tried to amalgamate them into this “union.”

Although the dynasty of the tsars came to an end with the 1917 Revolution, the idea of the Russian Empire seems certainly to have survived—in the atheistic and geopolitical expansionism of the Russian-led Soviet Union. But at the time such a re-shaped empire was not yet imagined; the fall of the tsars was good news to the Ukrainians, and they tried to make the most of their newfound liberty. They formed a sovereign state, and began planning for an autocephalous Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

Soon, unfortunately, the new state fell beneath the Bolsheviks’ onslaught; the new Church, however, was successfully formed and proceeded to perpetuate Ukraine’s unique cultural traditions. But the strengthening Soviet state could not long tolerate such a “nationalistic” church, and attempted in the 1930s to put an absolute end to any further “Ukrainianization” of the younger generations. The Ukrainian Orthodox Church was dissolved—violently; the only church to be tolerated—and that only barely—was the Russian Orthodox Church.

After World War II, when the Soviet government annexed the previously free western part of Ukraine, the Ukrainian Catholic Church was similarly forced to “reunite” with the Russian Orthodox Church, despite these Catholics recognizing only the pope’s authority, and not granting any credibility to an Orthodox patriarch’s pronouncements. Today, all that remains of hopes for uniquely Ukrainian churches is what is called a Ukrainian “Exarchate.” That is, Ukraine is theoretically an autonomous (but not autocephalous) portion of the Russian Orthodox Church, and that is its only Church. Thus, much as in the days of Peter I, the Russian Church is still being used as an instrument of “Russification” to further the aspirations of the Moscow government.

A great celebration: Crowds of Soviet believers, like this one photographed in 1983 during an elaborate Russian Orthodox outdoor Liturgy, will gather in even greater numbers throughout 1988.

The Soviet Celebrations

When the millennium celebrations in Moscow began, especially the Easter festivities, it was obvious that the spectacle was going to be impressive. But for quite some time beforehand, it seems, the Soviet leaders could not decide what to do about the millennium—torn between the Communist Party’s stance against religion and the massive popular surging toward the approaching anniversary, both in the Soviet Union and worldwide. Finally they reached a decision, and ordered that the entire USSR observe the occasion with pomp and ceremony. However, they shrewdly emphasized that it be a celebration of a “Russian” millennium.

As one of their first acts acknowledging the approach of the millennium, the Soviets in 1984 re-opened the St. Daniel monastery in Moscow, then gave it to the Moscow patriarchate. After that, government-approved workers began doing much in preparation for the millennium. Books were published. International contacts with leaders of other religious groups were initiated and solidified. Invitations went forth. And beginning at least as early es April of 1988, the celebrations began, though the biggest celebrations were reserved until June, the month in 988 when the baptism supposedly took place.

The June festivities were scheduled to include a solemn liturgy (worship service), led by Russian Orthodox hierarchs at the Patriarchal Cathedral of the Theophany in Moscow; a sobor (church council meeting) at the Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra (Monastery) near Moscow; a special festive gathering in Moscow, to be attended by invited representatives from various faith communities, as well as from the Soviet and other governments; other liturgies and masses at all the Churches of the Moscow Patriarchate; subsidiary celebrations in the cities of Kiev, Leningrad and Vladimir; and further celebrations in Kiev, to be attended by foreign guests and delegates from the sobor mentioned above.

Celebrations in other dioceses of the Moscow Patriarchate were to continue until mid-July of 1988, featuring Church services and gatherings of clergy and laitvy, at which the decrees and documents of the sobor were to be proclaimed.

In spite of the attention Patriarch Pimen was to give to the Kiev celebrations it was clear that Kiev, the actual site of the first mass baptism of Rus’, was being relegated to a minor position. Moscow remained predominant and pre-eminent in the celebration. Metropolitan Filaret of Kiev, when asked why this was so said dutifully, “Moscow has always been the center of the Orthodox Church of Rus’ ” (that is the literal translation the Ukrainian text of his comment; the English version says “of the Russian Orthodox Church”). The remark might be amusing—Moscow was hardly even a village in 988—if it were not such a tragic reminder of the subservience of the Church of Kiev, the “mother church,” to her eventually more-powerful and better-known daughter, the Church of Moscow. The Ukrainians’ laughter at this ironic remark could not help but be mingled with sighs of sorrow, frustration and yearning.

The Irony and the Anguish

With the ascendancy of the latest Moscow ruler, Mikhail S. Gorbachev, the Soviet Union seems determined to put on a human face before the watching world. A well-publicized religious celebration fits into these plans very well. The freedom—or at least tolerance—of religion in the USSR is made to seem like a genuine reality.

And there is an additional plum in this pie for the government. By making the millennium a “Russian” event, the pre-eminence of Russian language and culture in the multi-national USSR is given a welcome boost. The Soviet government follows in the footsteps of its tsarist predecessors in believing it is easier to rule over a unilingual domain.

Sadly, a good many Westerners don’t seem to mind this de-culturalization of the several non-Russian nations in the USSR. To view the Soviet Union as a multi-nation entity, and especially to try to differentiate between Russians, Ukrainians, and Byelorussians, seems to many like too arduous a task. How much simpler, they unconsciously think, to accept the simple, convenient labels proferred first by the tsars and now by the Soviets: “Russia,” “Mother Russia,” “Holy Russia.”

Thus it seems to have fallen largely upon the Ukrainians dispersed throughout the West to call the world’s attention to this inequity, to keep on raising such troubling questions as, Why is the baptism being primarily celebrated in Moscow, since it took place in Kiev? Why is the Ukrainian Catholic Church banned in its home country? Why was the Ukrainian Orthodox Church forced into the Russian Orthodox Church, and why can’t its autocephaly be recognized as it once was? As far as the primary celebration being in Moscow goes, numerous Ukrainians have pointed out that this is like celebrating the signing of the Magna Carta in New York, or the Declaration of Independence in London.

Annoying as these points might be, they must be raised, both by dispersed Ukrainians who are aware of the struggles of their countrymen, and also by those other concerned persons in the West who are aware of the series of injustices that the Soviet-approved celebrations are not acknowledging.

But some things it is already too late to do anything about. The big celebrations will go on in Moscow. Numerous VIPs will go and participate. The media will focus on the spectacle and ceremony, of which Moscow will certainly provide the most.

Yet there are still things that can be done. It would be in the interests of justice and true peace, if:

1) These questions were raised by those going to the celebrations in the Soviet Union;

2) Millennium celebrations by Slavic groups (particularly Ukrainian) outside the Soviet Union were heavily patronized (Ukrainians in many large Canadian and U.S. cities have formed Ukrainian Millennium Committees that will provide information about what is going on in each area. In Europe, the chief celebration of the banned and exiled Ukrainian Catholic Church was scheduled for July 3–14 in Rome. In the U.S., the chief celebration of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church was scheduled for Aug. 5–7 at its headquarters in South Bound Brook, N.J. The world celebration of the Ukrainian diaspora were scheduled for Aug. 12–14 in Ontario, Canada);

3) Readers would take time to better acquaint themselves with the complex issues of justice and peace in the USSR.

Bringing Back the Meaning

Unbeknownst to many Westerners, and surely as equally unbeknownst to many Russians, the thorny issues raised here bring anguished feelings to many Ukrainians and Byelorussians, feelings of anger and frustration verging on desperation. Many in the world probably do not realize the weight of emotion borne by the non-Russians as they watch this injustice being perpetrated on the sacred memory of the baptism of Kievan Rus’.

In the midst of all these politics, it would seem a good time to focus again on the greatest meaning of the millennium—that is, masses of people receiving Christ, who is love personified. It’s tragic that the commemoration of this event, instead of encouraging people to grow in love towards God and their fellow human beings, has become a means of asserting political aspirations, perhaps to some extent on the part of all parties concerned.

Thus it is important that the truth be spoken in love and heard in love, and that the way be opened for a fair and truly brotherly relationship among Ukrainians, Byelorussians and Russians of the various Christian communities, as well as among those who do not feel they can honestly belong to any of these faith communities, yet are genuinely concerned with human rights and values.

What’s really going on here? Dare we hope, despite the evidence against it, for the beginning of a new, honest, open relationship between peoples in the light of Christ who stands at the center of the baptism of Kievan Rus’?

The greatest need during this millennium is for love. It’s that simple.

And that difficult, as well.

Author of numerous articles and sermons, Dr. Ihor G. Kutash is the director of the Media and Information Commission of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada, and is the dean of the St. Sophie Ukrainian Orthodox Cathedral in Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Copyright © 1988 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine.Click here for reprint information on Christian History.