In this series

No modern biographer would ignore all of Jesus’ early life, as Mark does, or skip over his formative experiences as a young adult, as all Gospels but Luke do (Luke 2:41-52). Nor would a modern biographer of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, for example, spend half of his account on just the last week of his subject’s life, even if the person died tragically. And most modern historical works at least attempt to present themselves as reasonably objective.

But the authors of the four Gospels broke all these rules, especially the last. They were not disinterested observers of Jesus and his movement. No author who launches his work with the phrase “The beginning of the gospel about Jesus Christ, the Son of God” is pretending to write as a neutral reporter.

If the Gospels are not like modern works of history, neither are they like folklore. The time gap between the death of Jesus and the writing of the Jesus traditions (between 30 and 60 years) is too short to consider the Gospels as mere legends or folklore, which always have long gestation periods.

If they are neither modern biographies nor legends, what type of history do these Gospels contain? What do they reveal about Jesus? I believe upon close reading that three of the Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and John) are ancient biographies, and one (Luke) presents itself as an ancient history.

Revealing character

The Gospels were not written to give a chronology of Jesus’ ministry as much as to reveal who he was. Even markers that seem to be precise were only devices to move the narrative along. Mark, for example, frequently uses the term immediately in transitions, but he usually only means “after that.”

The authors did not have access to the extensive sources available today; besides, they were more interested in presenting what was typical and revealing of a person than in giving a blow-by-blow chronicle of each year of a person’s life. So ancient biographies were anecdotal by necessity.

Furthermore, most ancients did not believe a person’s character developed over time. Character was viewed as fixed at birth, determined by factors such as gender, generation, and geography; it was revealed gradually but consistently. Ancients also believed that how one died was especially revealing of one’s true character. This is one reason the Gospel writers spent so many words recounting Jesus’ last week.

One feature of the Gospels that troubles some modern readers is their lack of chronological precision, but this is typical of ancient biographies. Again, the focus is on the persons involved and what they did, not on the space-time coordinates of the event.

Jesus’ cleansing of the temple provides a fine illustration. While all four Gospels record only one cleansing, the fourth Gospel places this event near the outset, while the Synoptics (Matthew, Mark, Luke) place it during Passion week. A modern reader may think Jesus cleansed the temple twice. But this interpretation overlooks two points: (1) ancient readers would have concluded there was only one cleansing since no Gospel includes two such events; (2) the ancient audience was aware that a biographer had freedom to arrange his material in whatever fashion he felt most revealing of his subject.

In this case, the fourth Evangelist wished to stress at the outset how Jesus replaced the institutions of Judaism with himself (e.g., he is God’s Torah or Word, he is the temple, he is the source of new life and purity). Many ancient biographies, such as Plutarch’s Parallel Lives or Tacitus’s Agricola, were likewise more interested in events that reveal character than in a strict chronological record.

In some ancient historical (versus biographical) works, especially in the Greek tradition, there was more attention to chronology. This helps explain the “synchronisms” in Luke 3:1-2 or Acts 18:2. A synchronism tries to locate an event in divine history in relation to secular events, like the reign of a certain governor. Thus Luke-Acts would have seemed to ancients to be less biographical and more historical in character.

What can we depend on?

What kind of historical information, then, do the Gospels give about Jesus?

First, the Gospel accounts (especially Matthew, Mark, and John), present a good deal about Jesus’ character and how he was evaluated by his contemporaries. These character sketches, however, are largely indirect, and let Jesus’ words and deeds speak for themselves.

Second, the Gospel writers presented what they deemed were the salient facts readers absolutely must know to understand Jesus’ mission, person, and work.

Third, these writers presented this information in a broadly chronological way (e.g., Jesus’ birth obviously came before his ministry, and his ministry before his death), but they were not concerned with chronological minutiae (except, perhaps, in parts of Luke).

Fourth, this literature was written by and for a special community—a tiny minority in the Roman Empire—so they could know more about their Savior.

The Gospels also appear to have been written, in at least the case of the last three Gospels, for audiences that had inadequate knowledge of Jesus’ Jewish world, including the meaning of Aramaic words (Mark 15:34; John 19:13) and Jewish customs (Mark 7:3).

In the case of the fourth Gospel, the audience was not expected to have personally known the characters in the story (see John 11:2, 12:4,6). The Gospels, then, were by and large written for non-Jewish converts to Christianity.

Given all this, what can the discipline of history, using the Gospels as the main source, tell us about Jesus?

A birth that needed explaining

Jesus was born somewhere between 4 and 6 B.C. It might seem strange to suggest that Jesus was born “before Christ,” but this is due to an early miscalculation when in A.D. 525 Pope John I ordered a new calendar that would be reckoned from Christ’s birth. Regardless of the numbers, the Gospel accounts are clear that Jesus was born during the reign of Herod the Great, who died before this new calendar had begun counting the new era. In fact, Matthew 2:1-12 (where Jesus’ family flees to Egypt until Herod dies) suggests Jesus was born some time before Herod’s death.

The remarkable story of the virginal conception is found in two different accounts: Matthew 1:18-25 and Luke 1:26-38. What is most remarkable about these stories is that they try to account for something extraordinary that, so far as we can tell, Jews were not expecting—a Messiah coming into the world by means of a virginal conception.

Isaiah 7:14 in the Hebrew simply says, “Behold, the nubile young woman is with child and will bear a son,” though the later Greek version says, “The virgin will be with child, and will give birth to a son.” Still, it was not necessary to conclude that a miraculous conception was involved, only that a woman who had, up to that point, been a virgin, would now conceive. In other words, it was the anomaly of what happened at Jesus’ origins, not the Old Testament text, that led early Christians to search the Scriptures for an explanation.

At a minimum, the historical conclusion is that Jesus’ origins were unusual. It seems unlikely that early Christians would invent a story about a virginal conception knowing it would inevitably lead to charges that Jesus was illegitimate (a charge in fact we find in the third-century debate between Celsus the Jew and Origen, and one perhaps hinted at in Mark 6:3 and John 8:41). It was enough that their Savior had a scandalous death; early Christian writers were not looking to add more implausibility to the account.

The facts of youth

Though the Gospel writers, with the exception of the story in Luke 2:41-52 (Jesus talking with teachers in the temple), said nothing of Jesus’ youth, four things we know with a high degree of certainty.

First, Jesus grew up in a devout Jewish home. This is suggested by the birth narratives: Joseph is described as “a righteous man;” the family went to Jerusalem for the rites of purification after the birth; they attended Jewish festivals (Luke 2:41-52, John 7:2-5). By the time Jesus began his ministry, he knew the Hebrew Scriptures: he frequently quoted them in his discussions and debates and was even asked to read them in his hometown synagogue.

Second, Jesus grew up in Nazareth, a backwater town in Galilee. No historical scholar doubts this. It was not the kind of thing Jesus’ admiring biographers would make up, for no one was looking for a Messiah who came from Nazareth; indeed no one was looking for one who came from Galilee in general (John 1:46).

Third, in addition to knowing Hebrew, Jesus spoke Aramaic (a Semitic cousin of Hebrew) as his native tongue. It is also likely he knew at least some Greek (enough to deal with a centurion and a toll collector). Our earliest Gospel (Mark) stresses that Jesus prayed in Aramaic (15:34) and even used the Aramaic form of the word father (Abba, Mark 14:36) to address God. Jesus regularly identified himself to others using the Aramaic phrase bar enasha (“Son of Man”), an allusion to the figure spoken of in Daniel 7, one of the Aramaic chapters of the book.

Fourth, Jesus grew up in an artisan’s home. The traditions emphasize that Jesus was the son of an artisan, a carpenter, and may have been an artisan himself. Jesus was therefore not a peasant in the normal sense of that term (a poor person who makes his living by farming). He had a trade, which would have been considered an honorable thing in a Jewish or lower income Greco-Roman context (though the social elite of the Greco-Roman world looked down on anybody who worked with their hands).

A prophet, and then some

Jesus was about 30 years old when he began his public ministry (Luke 3:23), and the four Gospels imply his ministry lasted from one to three years (the latter is more probable). The Gospels, as ancient works, are interested in discerning the character of Jesus and his ministry, and they accomplish this by showing Jesus in relationships with various people and movements of his times.

First, there was his relationship with the prophet John, also known as “the Baptist,” which reveals something of Jesus’ relationship to all Jewish prophets.

All four Gospels explain that the ministries of John and Jesus were closely related. It is also clear that Jesus had great admiration for John and frequently compared himself and his ministry to John’s (Mark 11:27-33; Matt. 11:16-19). There may also have even been a period of joint or closely parallel ministry (John 3:22-4:6).

Most important, Jesus submitted to baptism at John’s hands, which not only validated John’s ministry but was a “watershed” event for Jesus. As for its historicity, the Gospel writers clearly would not have made up a story about Jesus’ submitting to John’s baptism: the baptism of a sinless Messiah (Heb. 4:15) was only another problem to have to explain.

During the baptism, Jesus, like other Jewish prophets, had a confirming vision and received an anointing from God for ministry. This call was unique, however, in that Jesus heard himself called God’s Son, and he later responded by calling God Abba, a term of intimate familiarity. The Gospel writers suggested that Jesus’ ministry was a confirmation and fulfillment of all prophetic callings. God’s final saving and judging activity was on the horizon, and God’s people needed to be prepared. They needed to repent.

Furthermore, Jesus’ ministry was more extensive than that of other prophets: he reached out to the rejected of society; he dined with tax collectors and notable sinners. While John, like other prophets, was something of an ascetic, Jesus was a convivial attender of parties and banquets (Mark 2:18-20; cf. John 2:1-12; Luke 19:1-9).

Jesus’ public utterances were another way in which he transcended the character of the Old Testament prophets, who prefaced their prophecies with “this is what the Lord says.” Jesus spoke on his own authority, and the Gospels also suggest that in an extraordinary gesture, he affirmed the truthfulness of his own teaching in advance by prefacing it with “I tell you the truth” (Mark 14:18, 30; Luke 23:43; John 3:5, 5:19).

The well-known story of John’s beheading (Mark 6:14-29) suggests that anyone with a following would have been considered a threat by Roman and Jewish authorities.

Prophets and messianic pretenders made those in power nervous. In this environment, it is not surprising that Jesus’ ministry was a short one. What is surprising, historically speaking, is that it lasted as long as it did. Jesus, like John, was seen as a political threat, even if he did not cast himself as a leader of some sort of revolt or protest movement (Luke 13:31-32).

Inner circle

The four Gospels further portray Jesus’ character by showing his relationships with his own disciples, both men and women (it is revealing that he dared, in an apparently unprecedented move, to have women followers in his itinerant group—Luke 8:1-3). That Jesus chose 12 is attested not only in the Gospels but in the earliest letters of Paul (1 Cor. 15:5). Jesus did not include himself among those 12, which suggests he saw himself not as a part of a reconstituted Israel but as a shepherd or leader of a new Israel.

Jesus’ relationship with his family is also revealing. A number of stories suggest his family did not fully understand him (Mark 3:21,31-35; John 2:1-12 and 7:4-5 and Luke 2:41-52). Indeed, the evidence suggests Jesus believed the coming of God’s final dominion meant primary loyalty was owed to an alternative family, the family of faith (Mark 3:31-35). Jesus called disciples away from their families and warned that physical families would be divided over him. It is hardly likely that the early church made up a saying like Matthew 10:34 (“I have come to turn a man against his father … “). This suggests that Jesus may well have been too radical for many in his own day who wanted to ground religion in family ties.

Did he know he was the Messiah?

Two themes most characterized Jesus’ preaching: his announcement that God’s saving reign was happening through his ministry, and that he was the “Son of Man.”

All the Gospels agree Jesus used this phrase to describe himself. It has strong claims of going back to Jesus himself, rather than being something the early church put on his lips. In Paul’s letters and in the Acts of the Apostles, Jesus is called “Christ” or “Lord.” Son of Man was not a title the early church usually used to refer to Jesus.

In combination with the phrase “Kingdom of God,” Son of Man suggests Jesus saw himself in light of the prophecy found in Daniel 7, where one like a “son of man” was promised an eternal kingdom. Furthermore, the Daniel text stresses not just the humanness of this figure but also his more-than-mortal character, for he is said to be destined to reign forever.

Some historians debate whether it was possible for Jesus to have believed such a thing about himself. Yet many messianic pretenders and contenders of the times (including Theudas and Judas the Galilean—Acts 5:35-39), made such claims for themselves. Why couldn’t Jesus have done the same?

Remarkable week

The Gospel writers spent their greatest efforts on the last week of Jesus’ life, largely to explain how a good man was crucified. The following events, historically speaking, transpired:

1. Actions and words by Jesus in the outer precincts of the temple provoked Jewish authorities to begin the process that led to Jesus’ death.

2. Jesus shared a final meal with his inner circle in which he forewarned the disciples about his demise but interpreted the event as connected to the redemption of God’s people, as the Exodus-Sinai events celebrated at Passover had been.

3. Jesus was captured in the garden of Gethsemane on the Mount of Olives (a frequent camping spot for pilgrims) as a result of a tip off by Judas, one of Jesus’ inner circle.

4. A pre-trial hearing, and possibly a hastily convened ad hoc trial by Jewish authorities, resulted in the handing over of Jesus to Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor.

5. A Roman trial was held, after which Jesus was executed on the eve of Passover on Friday, April 7, A.D. 30, on a hill called Golgotha, outside the city gates of Jerusalem.

6. Jesus was buried in a Judean sympathizer’s tomb near the site of the crucifixion.

7. An empty tomb was discovered the following Sunday morning.

8. Various followers of Jesus claimed to have seen Jesus alive.

The fact that Jesus’ shameful death is treated as something positive needs to be explained. Jesus’ earliest followers were Jews, and there is no hard evidence that first-century Jews were looking for a crucified Messiah. Nor did Gentiles see such a death in a positive light. It seems reasonable to conclude that there must indeed have been a rather remarkable sequel to this crucifixion to cause these Gospel writers and early Christians to diligently search the Scriptures looking for clues that would explain each aspect of Jesus’ last week.

Furthermore, it is not believable that the early church—in a patriarchal age in which women were not usually considered credible witnesses—would have invented a story about women being the first to see the empty tomb and the risen Jesus. This was not how someone in antiquity would construct a myth to win friends and persuade people.

An ancient would begin by supplying credible male witnesses, then add an impartial third party who could not be accused of wishful thinking or being delusional after the loss of their hero. A propagandist would also want to describe in detail the crucial event itself—remarkably, something not one of the four Gospels does.

From a historical point of view, an adequate explanation must be given for the exquisite and extensive acclamations of Jesus after his death. There were many prophets, sages, and messianic pretenders who walked the stage of the Holy Land before and after Jesus, but none spawned a world religion. Many charismatic Jewish leaders had died in more heroic fashion (e.g. some of the Maccabees), yet they did not create new forms of Judaism.

Even looking at the deeds and words of Jesus, one is hard pressed to find the basis of later acclamations: Jesus’ miracles were not unprecedented; his words, while remarkable in themselves, would not likely have started a Jesus movement among Jews, especially in light of his crucifixion. His relationships suggested a good deal about Jesus, but were they sufficient to have created the “Good News of Jesus Christ, Son of God”? I doubt it.

Explaining the resurrection

I am therefore left with the conclusion that the end of Jesus’ life and immediate sequel to his death must explain both the shape of the Gospels and the rise of early Christianity.

It is not an accident that in the earliest source about Jesus and early Christianity, Paul’s letters, the focus is on Jesus crucified and risen (Paul is the only once-hostile witness to have claimed to have seen the risen Jesus). To Paul, it seems, knowing Jesus’ deeds and words was secondary to knowing his death and resurrection: “For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins … that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day” (1 Cor. 15:3-4).

No, the Gospels aren’t modern biographies or modern histories, but the modern historian can still learn a great deal about Jesus’ life and times from them. Most importantly, I believe they reveal why Jesus, who had been known as the Son of Man during his life, came to be known, shortly after his death, as the risen Son of God.

Ben Witherington is professor of New Testament at Asbury Theological Seminary in Kentucky. He is author of the highly praised The Jesus Quest: The Third Search for the Historical Jesus (InterVarsity, 1997).

The Humane Side of “the Extreme Penalty.”

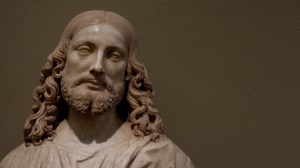

The philosopher Cicero said crucifixion was “the most cruel and hideous of punishments.” Others just called it “the extreme penalty.” As such, Rome reserved it for the worst elements of society: murderers, revolutionaries, and slaves. Contrary to popular depictions, Jesus was probably crucified, as in this picture, without any covering and in this cramped position.

Though designed to be a slow and painful death (and thus a deterrent), some practices were instituted to make it more humane. The condemned were usually first stripped, tied to a post, and given 39 lashes with a short whip that held tiny, lead balls that would bite into the flesh and cause bleeding—to hasten death once on the cross. Breaking the legs of the crucified, which constricted the chest and lungs and made breathing finally impossible, was another means of bringing death on more quickly.

Without such measures, victims would hang in agony for days on end.

—Mark Galli

Copyright © 1998 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.