“Are you intending to sail to Greenland this summer?” Norway’s King Olaf Trygvesson asked Leif Eriksson, whose father had founded the island colony.

“Yes,” Leif replied, “if you approve.”

“I think it would be a good idea. You are to go there with a mission from me, to preach Christianity in Greenland,” said the king credited with the conversions of Norway, Iceland, Orkney, Shetland, and the Faroes. “Your good luck will see you through.”

But on his way home Leif was blown off course, landing far southwest of Greenland, in a land now known as Newfoundland.

So says Erik’s Saga, which, like other such stories, is part truth and part fiction. What is known is that the story surrounding Erik the Red and his son Leif Eriksson (or “Leif the Lucky”) spans many generations. It begins during the ninth century with political violence in Norway and ends in fifteenth-century Greenland as one of the unsolved mysteries of medieval Europe.

A cunning outlaw

Erik and Leif traced their origins back to Norway and Iceland. After a series of bloody campaigns, the ninth-century Norwegian King Harald Fairhair consolidated all of Norway under his rule. Unwilling to submit to Harald’s authority, provincial rulers and district strongmen emigrated to establish farming settlements in Iceland. Though formally devoted to the rule of law, these Icelandic farmers were often governed by relentless family feuds and their own violent passions.

In the late tenth century, Erik the Red and his father, Thorvald, left their home in Norway “because of some killings” and settled in Iceland. When Thorvald died, Erik married and established a farm.

Blood troubles soon caught up to them across the Norwegian Sea. As Erik’s Saga tells us, Erik’s slaves “started a landslide that destroyed the farm of a man called Valthjof . …So Eyjolf Saur, one of Valthjof’s kinsmen, killed the slaves . …For this, Erik killed Eyjolf Sauer; he also killed Hrafn the Dueller . …Eyjolf’s kinsmen took action over his killing, and Erik was banished.”

After even more bloodshed during his exile in the early 980s, Erik and three followers sailed westward to the previously sighted but yet unnamed Greenland, where they spent three summers and winters exploring the land.

Though forbidding to modern readers, such rigors seem not to have fazed the expedition members. Viking voyagers loved nothing more than a challenge. In addition, modern studies of core samples from the Greenland ice sheet show that during the Viking era, North Atlantic regions were undergoing a warming phase, a so-called climatic optimum, which allowed for animal husbandry and some agriculture in areas where they are now unthinkable.

In 985 Erik led a full-scale migration of Icelanders to the world’s largest island, which he named Greenland, “for he said that people would be much more tempted to go there if it had an attractive name.” Of 25 ships filled with settlers, only 14 completed the stormy, 200-mile journey.

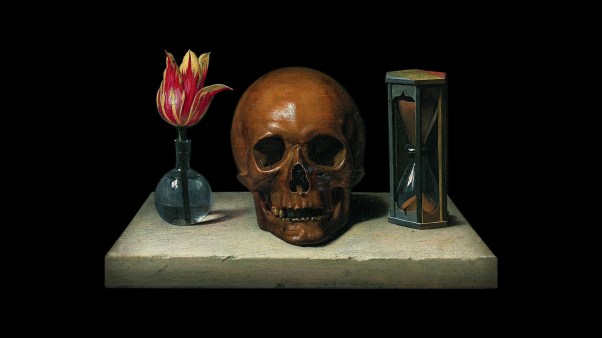

The Norse colonies they set up in the new land were pagan, devoted to the Viking deities, known as Aesir (Odin, Thor, etc.). Though ethnically and religiously similar, the settlements were geographically separate. Located in southwestern Greenland, they were known as the Eastern and Western settlements, an adventurous brave new world at the very limits of Viking expansion.

As the colonies’ leader, Erik built his farm on choice land at Brattahlid in the Eastern Settlement, where he lived until his death (possibly of an epidemic) sometime around the year 1000.

We catch glimpses of his personality: Greenland Saga says “he commanded great respect” and people “recognized his authority.” He was most likely temperamental, as the aforementioned killings suggest, and certainly a devout follower of the pagan gods, especially the thunder god Thor.

Versions of conversion

While Erik’s flight to Greenland gave his public life a stability he had not known in Norway or Iceland, the introduction of Christianity divided his family. Though the story from Erik’s Saga credits Olaf Trygvesson, the new faith probably spread to Greenland via Iceland, which had been Christianized under Olaf’s influence.

As elsewhere in Scandinavia, the Christianization of Greenland was likely a gradual process urged on by monarchs and clergy from abroad as well as by local leaders. Pagan and Christian practice existed side by side for decades: we read the numerous tales of pagan witchcraft and superstition in the Vinland Sagas, many taking place supposedly after the conversion to Christianity.

Other sources insist that Leif Eriksson himself introduced the faith. Greenland Saga describes Leif as the opposite of his father: “tall and strong and very impressive in appearance” and “always moderate in his behavior,” characteristics clearly in line with Christian virtues.

Furthermore, Leif represented the new order, the younger generation that introduced Christianity and replaced the pagan ways of Erik’s generation. In Erik’s Saga we read, “Erik was reluctant to abandon his old religion, but his wife, Thjodhild, was converted at once, and she had a church built not too close to the farmstead . …Thjodhild refused to live with Erik after she was converted, and this annoyed him greatly.” Following this episode, Erik slowly fades from the sagas, the implication being that he is isolated in the new dispensation.

Separating fact from fiction is difficult. In the twentieth century archaeologists have excavated the Norse settlements in Greenland, including Brattahlid, where they discovered the remains of a chapel that may correspond to “Thjodhild’s church.” Likewise, excavations in Newfoundland prove that Vikings indeed later settled in Leif the Lucky’s Vinland, even if only for a short time. Were they the first Christians in the New World? We’ll likely never know.

By whatever process Christianity reached medieval Greenland, it remained a potent force there for over 400 years. After Leif’s time, the Catholic Church sent clergy to the distant island, and the Norse settlers built numerous stone churches. But by the 1400s, the Norse settlements had mysteriously languished as the population dwindled and disappeared, leaving only their stone buildings as testimony to a once thriving Christian community, estimated at 4,000 to 6,000 souls.

In the Icelandic annals, the last notations from Greenland tell of a wedding held there in the early 1400s. After that, all is silent.

Roger McKnight is a professor at Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minnesota, where he specializes in Scandinavian literature.

Copyright © 1999 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.