America is living with a deep racial wound. Many, today, are limping. They're hurting. Not a day goes by that racism relinquishes its visceral sting on our broken world. Yet, it's possible for many of us to ignore issues of race in America, to not see the pain around us.

The racial divide—and more broadly, a divide over privilege—has come to light again this week in the wake of the Trayvon Martin trial. As Americans react to George Zimmerman's "not guilty" verdict, I've heard, in the cries of many, that members of Christ's body have been suffering alone.

"I was and have remained in shock. No—not shocked—devastated and dumbfounded, at a loss for words," wrote Enuma Okoro, for Q Ideas. The words "not guilty," and the deafening ecclesial silence afterwards, sound too much like, "Your suffering is discountable."

From a Christian perspective, that's hugely problematic. In Christ, we've been knit together, across racial divides, as one body. The Bible affirms we are conjoined, our interests so intertwined that there is no such thing as suffering alone. When the apostle Paul described the way the body of Christ was designed to function, he taught "that there should be no division in the body, but that its parts should have equal concern for each other. If one part suffers, every part suffers with it." (1 Cor. 12:25-26).

The concern that Paul describes, so central to the church's identity, has been largely absent from not only the responses to the recent trial but to decades of wounds within the church.

The kairos—time-is-right—invitation for many believers today is to open our eyes and ears to the hurting members of the single body whose head is Christ.

This week, those who suffer include many African Americans. But we also need to wake up to the pain of many more to whom we are joined: believers in China, Latino immigrants to the United States, people with disabilities, and many others.

Some dismiss these groups and their experiences as being tied up in current issues that are not the concern or responsibility of the church. But that's not the case. Paying attention to the experience and suffering of others isn't about being politically correct. Neither the metric of tolerance nor the metric of relevance were ever meant to measure the church's response to a world in need. Rather, the church gleans her identity from the person of Jesus and the counter-cultural kingdom he built and continues to build. Our very unique calling is to behave as the living body of Christ in the world today.

If we're to move together toward healing, this is the moment to face the infection that is poisoning us all.

1. Look

Facing the enduring sting of our country's race history is necessarily uncomfortable. The first step toward health is to be willing to open our eyes and see. As you watch the news this week—even the most angry protests—ask the Spirit to open the eyes of your heart to see and understand suffering in a new way.

2. Listen

During these days, brothers and sisters of color in the church are our skilled diagnosticians who can point us to the Good Physician. Though it takes a great deal of energy and vulnerability and courage, many fellow Christians are willing to give this gift. Ask a friend at church or work to share with you their thoughts on the trial, the coverage, race, or whatever's on their mind. Take time to really listen and understand their perspective.

3. Speak

As your eyes and ears are opened, dare to speak. This past Sunday morning there were thousands of churches across the nation who prayed for unity and healing in the wake of the recent verdict. In thousands more, no word was mentioned. Something as simple as asking your congregation to pray is one step toward healing.

4. Pray

One local church in my area that is deeply committed to racial reconciliation has discovered together that issues of race are more slippery and wily and confounding than they ever imagined. Driven to our knees, we depend upon the anointing of the Holy Spirit to heal the divides which have separated us for too long.

As someone who, for years, survived emotionally by turning a blind eye to my own emotional wounds, I get it. As someone who still feels weary coming close to the pain of others, I understand. Facing pain, whether our own or that of others, can be uncomfortable, sad, and painful. But to ignore the cries of our brothers and sisters during these days is to allow the ancient wound to fester untreated. It is to deny the reality of the gospel of Christ by behaving as if we are not one body.

By Paul's logic, if we're not suffering alongside other members of the body, we're not being the church. God give us the courage to suffer together.

Margot Starbuck, an author and speaker in Durham, NC, is the author most recently, of Permission Granted: And Other Thoughts on Living Graciously Among Sinners and Saints. Connect on Facebook or at MargotStarbuck.com.

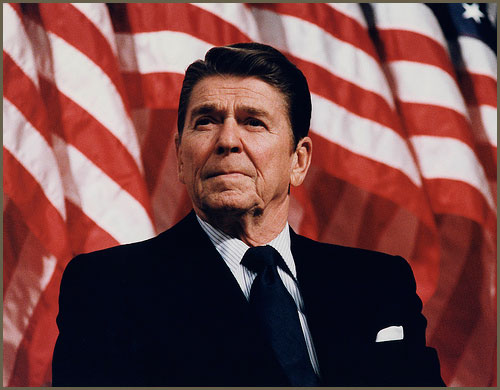

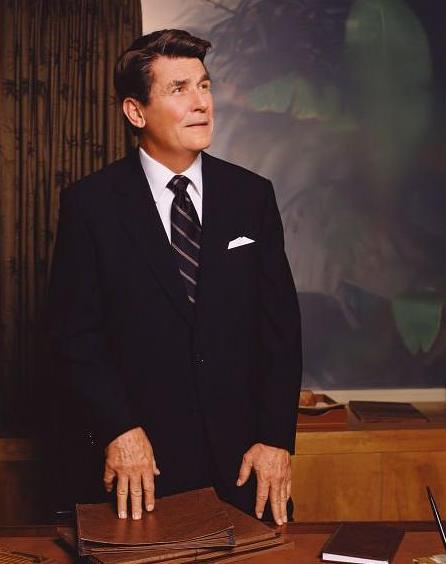

It’s surprising that there hasn’t yet been a biopic of Ronald Reagan, one of the most-loved Presidents in U.S. history. But that’s about to change, thanks in much part to a pair of Christian producers in Hollywood.

Ralph Winter (X-Men and Fantastic Four movies) and Mark Joseph are co-producing the film, simply titled Reagan. An actor has not yet been chose to play the part, but speculation has already begun here.

Joseph, who worked on Ray, Holes, and The Passion of The Christ, says that much of the tone and script will be based on two Reagan biographies by historian Paul Kengor, God and Ronald Reagan and The Crusader: Ronald Reagan and the Triumph Over Communism.

Joseph tells CT that “it’d be impossible not to” focus on Reagan’s spirituality, given the source material of those two books. “You can’t understand Reagan if you don’t understand where he came from. . . . Kengor went to the church Reagen grew up in and asked to see the sermons he would have heard as a child. They were in the basement, and previous Reagan biographers hadn’t exactly kicked down the door to read them.

In the last few years Instagram has developed into a major social phenomenon. Apple claims iPhone is "the most popular camera in the world," and as of June 2013, Instagram boasted 130 million users, with an output of roughly 40 million photos a day.

Due to the sheer volume of the photos coming at us each day, it's easy to become an Instagram cynic.

How many of us have lamented the inundation of "check out my perfect life" photos on our Twitter and Facebook feeds? How many of us have seriously considered unfollowing the person who shares pictures of her delicate wine glass sitting atop a rustic wood table overlooking the beach? Or the guy who posts a picture of every meal he has ever eaten?

These frustrations can be real and valid. Instagram can contribute to a Christian culture that is inauthentic and comparison-driven.

However, it doesn't have to. My motives for using Instagram are many, but not all bad. I often post photos, not to show off my perfect life, but to invite others to share in my joy. That is a motive of a different kind.

Take last week, when I found myself staring at a picture I had captured of my baby boy's open-mouthed belly laugh. I knew my friends would enjoy it, but I also debated whether or not to share it: What about my friends who get annoyed by baby pictures? What about my friends struggling with infertility? Am I turning into that woman who constantly posts pictures of her kid?

In the end, I chose to share the photo, reminded of a passage from C.S. Lewis' book Reflection on the Psalms. In it he explains the compulsion to express one's joy outwardly, writing,

I think we delight to praise what we enjoy because the praise not merely expresses but completes the enjoyment; it is the appointed consummation. It is not out of compliment that lovers keep on telling on another how beautiful they are; the delight is incomplete till it is expressed. It is frustrating to have discovered a new author and not be able to tell anyone how good he is; to come suddenly at the turn of the road, upon some mountain valley of unexpected grandeur and then to have to keep silent because the people with you care for it no more than for a tin can in the ditch; to hear a good joke and find no one to share it with (the perfect hearer died a year ago).

This is so even when our expressions are inadequate, as of course they usually are. But how if one could really and fully praise even such things to perfection–utterly 'get out' in poetry or music or paint the upsurge of appreciation, which almost bursts you? Then indeed the object would have attained perfect development.

Lewis goes on to argue that the compulsion to praise that which we enjoy lies at the heart of Christian worship. He adds:

The worthier the object, the more intense this delight would be. If it were possible for a created soul fully (I mean, up to the full measure conceivably in a finite being) to 'appreciate,' that is to love and delight in, the worthiest object of all, and simultaneously at every moment to give this delight perfect expression, then that soul would be in supreme beautitude….In commanding us to glorify him, God is inviting us to enjoy him.

I don't want to make too much of a thing like Instagram; my intent here is not to over-spiritualize. Nonetheless, I do find Lewis' perspective to be redemptive for the use of social media. It provides me with a lens for filtering my own motives, as well as the motives of others.

When a friend posts a photo of her European vacation, or a beautiful sunset, or her baby's latest milestone, her intentions may not be self-absorbed or vain. Perhaps, instead, she is inviting me to share in her joy. Perhaps she is participating in an act that reflects the very heart of praise.

As with any invention on earth, our sinful hearts will always find a way to corrupt it. That is a truth that should sober us as we submit our hearts to the Spirit's purifying work. Even so, I see some good in Instagram. It's just possible that Instagram is schooling us in the art of praise.

Maybe, in our enjoyment of everyday, even mundane loveliness—delectable meals, breath-taking landscapes, and hilarious kid disasters—we will remember to turn our praise and enjoyment toward the One from whom they all come.

“Those sermons, a book he read as a child called That Printer of Udell’s, and the influence of his mother Nelle set him on a course for, as he might have said, a rendezvous with destiny. It would be impossible to understand Reagan without understanding his spiritual roots.

“At the same time, we balance that with Kengor’s other book, The Crusader, which is about foreign policy intrigue and the nuts and bolts of how Reagan accomplished what he did. Taken together, the two books address both the spiritual and the temporal.”

Jonas McCord wrote the script despite not being a gung-ho Reagan fan. “I was of the opinion that at best he was a bad actor and at worst a clown,” McCord told The Hollywood Reporter. But after doing his research, McCord saw the possibilities.

Joseph defended his choice of writers: “Jonas wasn’t a rah-rah Republican. But over time he came to understand what a consequential man and president Ronald Reagan was. He came to the material open minded. And when I sent him to Reagan’s old haunts in Dixon, Illinois, and Eureka College he discovered a deeper appreciation for the man. But I’m not afraid to have people involved who may not be dyed-in-the-wool fans but nonetheless appreciate the man and his contributions. But ultimately it’s my job to make sure the film stays true to who he was and lives up to the expectations filmgoers will have.”

McCord told The Hollywood Reporter that Reagan’s childhood was like “a surreal Norman Rockwell painting with his alcoholic Catholic father, devout Christian mother, Catholic brother and ever-changing boarders the family took in.”

Joseph says he was drawn to the project because Reagan “lived a fascinating life and he looms large over the American landscape in ways that we don’t even think about. He was also an enigmatic person. His official biographer called him ‘inscrutable.’ All of which makes for a great movie. There are very few stories that have near 100 percent name recognition and this is one of those special American stories.

“He was much more than a President to a lot of people like me. He was one of the only public figures who didn’t let my generation down. I came from a generation of the anti-hero: Nixon had Watergate, Carter had malaise. Religious leaders like Swaggart and Bakker couldn’t live up to what they professed. But Reagan never wavered.”

Christians, more than anyone else, should be uneasy with animal suffering; yet, many view animal welfare as a secular humanist concern, leaving it to others to lead the charge to care for God's creatures.

Amid the perplexing dearth of Christian influence in the area of animal protection, Eric Metaxas highlighted on BreakPoint a New York Times story on the role an evangelical Christian—National Institutes of Health director Francis Collins—played in releasing hundreds of government-owned chimpanzees.

Collins teamed up with the famous Jane Goodall to retire nearly 360 of the NIH's chimps, releasing them into an animal sanctuary after they spent most or all of their lives in laboratory cages.

A 2011 study determined that chimps are unnecessary for most biomedical and behavioral research, and the U.S. is the only developed country that continues to use chimpanzees for invasive research and testing. Hundreds more chimpanzees will remain in other government-run laboratories after the release of these retired primates.

Their release is good news for taxpayers and anyone who loves happy animals. Just watch this video of other retired chimps being freed for the first time, and you'll see what I mean.

Christian thinking tends to be foggy on matters of animal protection, especially when we believe that their suffering will somehow benefit humans, forgetting that animals weren't created to save us. Leadership from someone like Collins in matters of humane stewardship of animals is welcome news indeed.

Many Christians accept or ignore the wide-scale suffering of animals under the justification of scientific "progress" or cheap meat (as a meat-eater, I include myself here). This perspective, though, reflects the influence of a modernist worldview more than biblical thinking.

After all, it wasn't the Bible but rather the father of modern philosophy, René Descartes, who helped popularize the idea that animals are mere machines to be put to human service. "Here is my library, from which I take my wisdom," Descartes told an observer as he dissected a calf. Descartes' disciples are said to have kicked their dogs and laughed to hear the "creaking of the machine."

In contrast, while the Bible mandates humans in Genesis 1:28 to rule over animals, other passages make clear that we are to do so with kindness: the Scriptures tell us not to muzzle the ox while it treads the grain and that the righteous one has regard for the life of his beast.

More biblical thinkers than Descartes and his disciples have also taught compassion toward animals. John Calvin said that we are to "handle gently" the animals God placed under our subjection. John Wesley proclaimed in his sermon "The General Deliverance" that the animal kingdom is included in God's salvation. William Wilberforce, Hannah More, and other 19th-century abolitionists included animal welfare in the reforms they succeeded in bringing to Great Britain.

And C. S. Lewis bucked the prevailing thought of his academic peers in opposing animal experimentation, using the strongest terms:

The victory of vivisection [animal experimentation] marks a great advance in the triumph of ruthless, non-moral utilitarianism over the old world of ethical law; a triumph in which we, as well as animals, are already the victims, and of which Dachau and Hiroshima mark the more recent achievements. In justifying cruelty to animals we put ourselves also on the animal level. We choose the jungle and must abide by our choice.

We don't need to debate the role animal experimentation has played in the past to acknowledge that now the practice is outmoded and largely unnecessary, the vestige of an archaic and unbiblical brand of empiricism. We need not continue the suffering simply because it is how things were done for so long.

Furthermore, most Christians—who help comprise the American population that spends billion annually on pets—love their own pets and see them, as I certainly do, as members of our families. We could never imagine one of our beloved pets undergoing the treatment given to countless animals in laboratories and industrial farms every day.

We might then ask ourselves if our horror at such a thought is rooted in a perspective that treats animals with compassion only out of mere sentiment or possession—or from of a more biblical view in which all animals—not only the ones we call our own—are seen as God's creatures? Can we—should we—love our neighbor's animals as our own?

Perhaps releasing these retired chimps where they can live out the rest of their days free of cages and pain is one small step for them—and one giant leap for humankind.

Karen Swallow Prior is a member of the Faith Advisory Council of the Humane Society of the United States.

The only thing close to a Reagan biopic so far was a 2003 TV miniseries, The Reagans. That less-than-reverent project, starring James Brolin as the President (pictured at left), was supposed to air on CBS, but a controversy over alleged left-wing bias erupted, and it was shifted to Showtime instead, and seen by only 1.2 million people, according to The Hollywood Reporter.

“Only in Hollywood could you make an insulting, condescending movie about a much-loved historical figure,” Joseph told The Hollywood Reporter. “Hire an actor who loathed the man. Watch it flop and then somehow conclude that Americans don’t want to see a movie about him. I watched Americans line up and wait for 10 hours for the simple privilege of passing by his closed casket. They loved this man.”

Brolin disagreed with Joseph’s assessment of the miniseries, and says he admired Reagan: “He’s literally our best icon in recent years. He represented America quite well. There were some clandestine things going down, but for the most part I think he was a good president.”