April was a terrible month for Ethiopian migrants. Tescma Marcus and his brother Alex were burned alive during xenophobic attacks in South Africa. One week later, Eyasu Yekuno-Amlak and his brother Balcha were dramatically executed in Libya by ISIS, along with 26 others.

One reason Ethiopians were involved in high-profile tragedies at opposite ends of the continent: Their nation is the second-most populous in Africa as well as the second-poorest in the world (87 percent of Ethiopia's 94 million people are impoverished).

Roughly two-thirds of Ethiopians are Christians. The majority of these belong to the ancient Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church; the rest primarily to Protestant denominations such as the Ethiopian Evangelical Church Makane Yesus (which recently broke ties with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America over theological concerns).

The Orthodox and Protestants have long had in common the search for a better life. Increasingly, they share even more.

Veteran SIM missionary Howard Brant celebrates that “the two groups are coming closer and closer together” in Ethiopia, which he calls “one of the great success stories of evangelical Christianity.”

The martyred migrants in Libya, he said, likely belonged to the Orthodox church. “But if they were strong enough believers to refuse to deny Jesus on pain of death,” he said, “then God knows their hearts.”

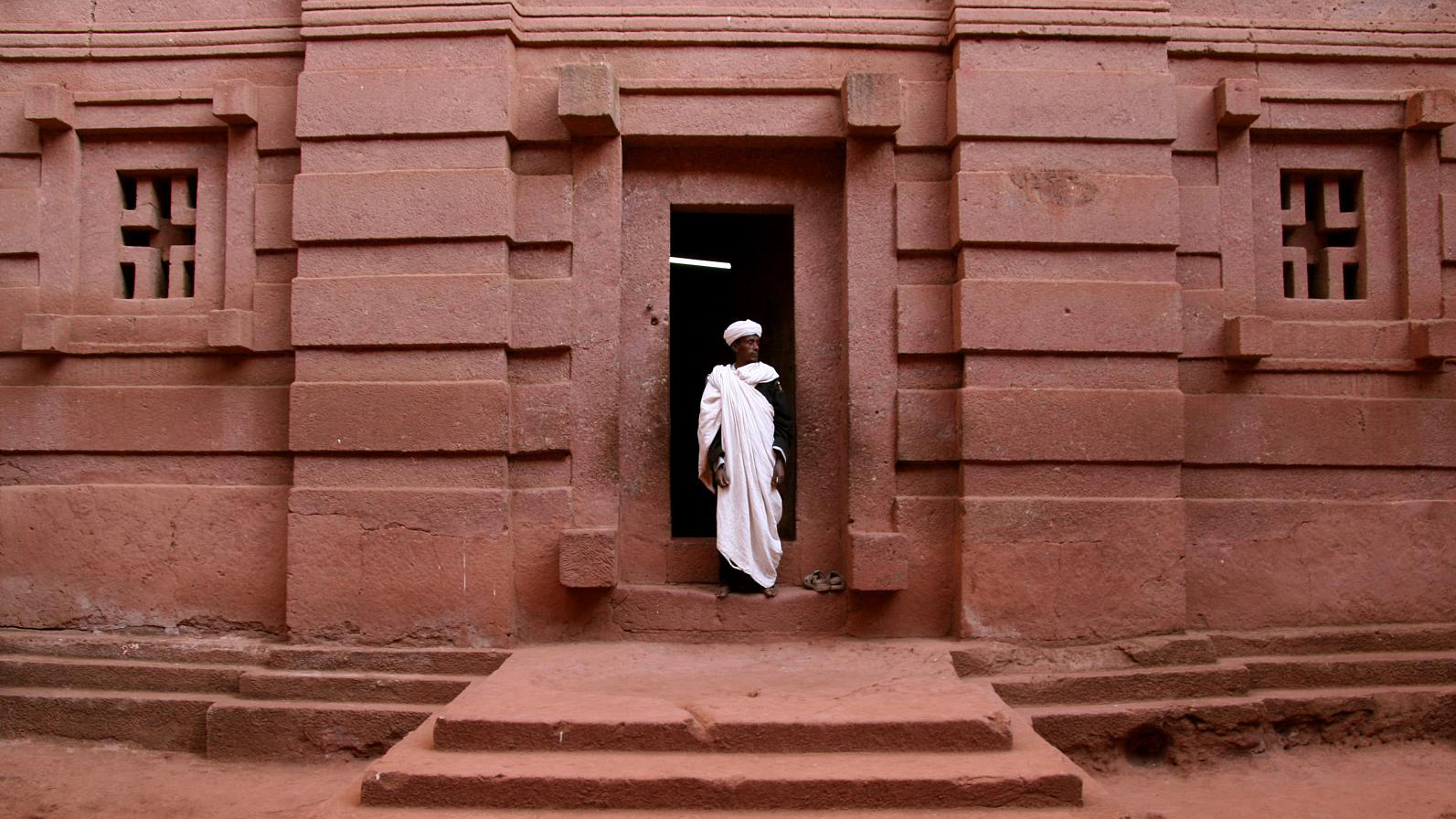

The Tewahedo church—like its Orthodox sister church in Egypt—celebrates its history of martyrdom. It claims descent from the Ethiopian eunuch converted by Philip in Acts 8, and dates formally to the preaching of Frumentius in the early fourth century and the acceptance of Christianity in A.D. 330.

The name means "unified" in Ge’ez, the ancient and still liturgical language of Ethiopia. It refers to Christ’s one nature, both human and divine. In A.D. 451, the Oriental Orthodox churches rejected the Council of Chalcedon’s pronouncement of his two natures.

But despite joint confession of the A.D. 325 Nicene Creed, relations with Ethiopian evangelical groups have traditionally been poor. The Orthodox hold to an 81-book canon of Scripture, engage in deep veneration of Mary, and believe the Ark of the Covenant is housed in their St. Mary’s of Zion Church, said to be brought in the 10th century B.C. and kept in secret.

Some evangelicals accept the ark legend as well, said Ralph Lee, an expert in Ge’ez and Ethiopic theology who has partnered extensively with the Orthodox. Despite these barriers, he believes there is much room for cooperation.

“The gospels always come first and all is to be interpreted in their light,” he said. “There are many within the church who are seeking to help the laity develop a better understanding of their faith and its meaning.”

Unfortunately, he says, there are others who do not fully realize the importance. The Bible is widely available in Amharic, the national language, and the Bible Society in Ethiopia works with all denominations. But some Orthodox bishops oppose a vernacular liturgy, and priests are generally not given an academic education in the Scriptures.

One bishop, however, has authorized a Bible translation in the local language of the heavily Orthodox region of Tigray, along the northern border with Eritrea.

The Orthodox church’s late leader, Patriarch Abune Paulos, was hailed by Lee and many Ethiopians as a champion of ecumenism, serving as a president of the World Council of Churches until his death in 2012.

Over the last decade, the patriarch allowed an SIM missionary to teach an AIDS prevention course in the Orthodox church's Holy Trinity Theological College. Instructing priests and monks, they partnered to launch an awareness campaign at a time many Ethiopians were still wary of the afflicted and evangelicals alike.

The pioneering collaboration led to Lee and other foreigners being invited into Orthodox seminaries, where they have taught for several years. But residual distrust among the non-academic wing of the church has at least temporarily restricted further cooperation.

“Some evangelicals believe the Orthodox are not fully Christian,” said Lee, “and some in the Orthodox church have resisted—rooted in a deep-seated suspicion of foreigners.”

Ethiopia takes pride as an African nation that did not fall to colonialists, despite the best efforts of Italy. But World War II ended its ambitions, after which Emperor Haile Selassie allowed foreign missions to work among Ethiopian animists for the medical and educational benefits derived in the less developed—and non-Orthodox—southern regions of the nation.

After the Marxist revolution of 1974 and expulsion of the foreign missionaries, Ethiopian churches witnessed explosive growth. Today, per the most recent census, nearly a fifth of the population is evangelical (19%, compared to 44% Orthodox).

The constitution guarantees religious freedom, but non-Orthodox must register with the government. There is a sense the “Pente,” so called for the charismatic leanings of these churches, are still foreign.

But like the Orthodox, Muslims are recognized as an indigenous community. Woyita Olla, deputy general secretary of the evangelical Kale Heywet (“Word of Life”) Church (which evolved from SIM work), says relations with Muslims are good.

“The incident in Libya has no religious basis,” he said. “It is a brutal, inhuman act that has no support among Muslims or Christians. We are all condemning it.”

Olla works closely with Muslims on the national interreligious council of Ethiopia, even as he cherishes the right of each community to evangelize the other. Muslims compose about a third of the population, and are said to have arrived in the seventh century when the Christian king of then-Abyssinia welcomed the persecuted followers of Muhammad.

Following the Orthodox lead, Kale Heywet announced a week of prayer and fasting following the killings in Libya. Olla agrees interdenominational ties are strengthening, as the nation is coming together.

But according to one Ethiopian Christian medical worker who preferred not to be named due to the sensitivity of the situation, Ethiopia is coming together in frustration.

“Children and the elderly are physically sick from what they have seen from ISIS,” he said. “But there is also anger at the government for not controlling immigration and creating more job opportunities.”

Tens of thousands of Ethiopians joined a government-sponsored rally three days after the killings. By the end, riot police had to subdue parts of the crowd.

“We may have some weakness in handling domestic issues,” said Girma Bekele, an Ethiopian adjunct professor of global missions and development studies at Wycliffe College in Toronto, Canada. “But to any foreign aggression the country is always strong and united, irrespective of ethnic or religious identities.”

Bekele was saved during the period of Marxist oppression and joined Kale Heywet. He hopes that improving religious relations will push all Ethiopian churches toward justice and concern for the poor.

And he has circulated a pastoral letter, acknowledged by Brant and Ethiopian leaders back home, hoping to contribute.

“The massive exodus from the country by any means and at any cost speaks strongly about the need to struggle against the crisis of poverty,” he wrote. “The plight of the poor, the great majority, is and must be at the heart of national discourse.”

In 2011, the Ethiopian Ministry of Foreign Affairs estimated that more than 75,000 citizens migrate annually to Libya, most with the hope of making it to Europe. Italy is the leading Mediterranean nation of reception, with about 10,000 Christian migrants from Ethiopia, according to the Pew Research Center. Many get stranded; others die trying.

The nation’s Ministry of Justice announced it is drafting a new law to combat human trafficking, and is working to repatriate Ethiopians in Libya.

Bekele calls for more, including the rescue and economic reintegration of migrant Ethiopians threatened also in Yemen and the Sinai. But while he laments the state of his country, he looks to his once and future church in hope.

“I am optimistic this national grief will usher in a new paradigm for the church in Ethiopia,” he said, “as leaders work tirelessly to transform it into missional dialogue.

“We have endured challenge from within and without, and must stand in prayer as a resilient Christian nation, worthy of its 1700-year heritage.”