The more you go to church, the less likely you are to see science and religion as incompatible, according to the latest Pew Research Center survey.

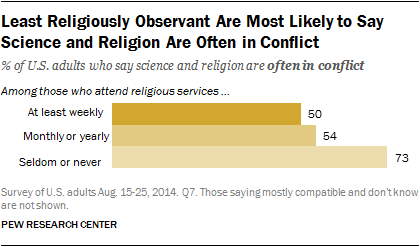

Half of Americans who attend religious services weekly said science and religion are often in conflict, less than the 54 percent who attend monthly or yearly, and far less than the 73 percent who seldom or never attend.

“It is the least religiously observant Americans who are most likely to perceive conflict between science and religion,” stated lead author Cary Funk in today's report.

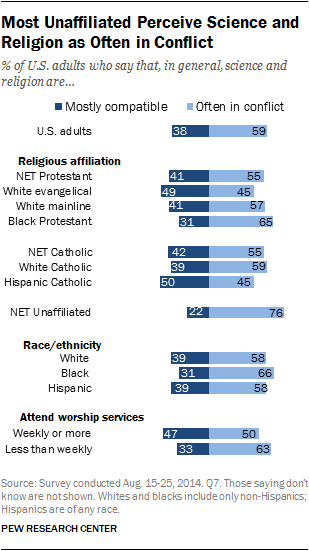

White evangelicals are especially likely to say that science is compatible with faith: almost half (49%) agree, compared with 38 percent of all US adults. About three in ten (31%) black Protestants (two-thirds of whom identify as evangelical according to past Pew research), also said science and religion are mostly compatible.

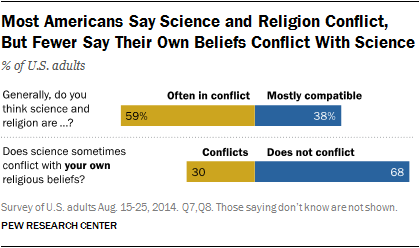

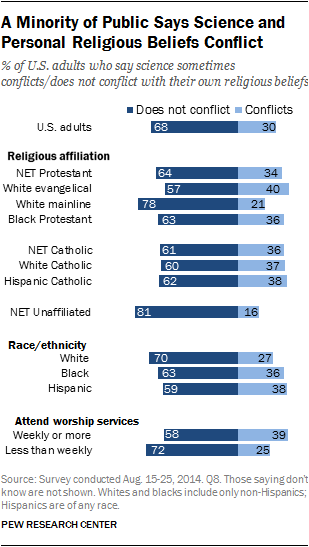

But while almost 60 percent of Americans think science and religion often conflict, only 30 percent think science conflicts with their own religious beliefs, down from 36 percent in 2009. The drop was driven by the religiously affiliated, which fell from 41 percent to 34 percent; the religiously unaffiliated, or so-called “nones,” stayed constant at 16 percent.

“People’s sense that there generally is a conflict between religion and science seems to have less to do with their own religious beliefs than it does with their perceptions of other people’s beliefs,” Pew stated.

Evangelicals experience more personal conflict than the general public: 4 in 10 said their own beliefs sometimes conflicted with science. But even that number has decreased from 52 percent in 2009.

The biggest area of contention that respondents mentioned: creation and evolution. More than a third (36%) said religion collided with science over issues of creation, evolution, and Darwin. About a quarter (24%) said there were broad differences over the belief in God, existence of miracles, and view of whether man is actually “in charge.”

Only about 1 in 10 (11%) said abortion is an area of conflict, while another 7 percent thought science conflicted with religion in specific medical practices.

Indeed, religious persuasion affected just a few areas of science that Pew asked about. While those with a religious affiliation don’t think the world’s growing population is a problem, and while 6 in 10 of those who regularly attend worship services say genetic modification of babies is “taking medical advances too far,” religion didn’t affect opinions on other scientific topics including:

- Whether to allow access to experimental drug and medical treatments before they have been fully tested.

-

A while ago I went back to college with my daughter. Aside from some summer in-service training in the Theological Seminary at Princeton in buildings and under conditions which change little and which her graduates remember with nostalgia, I had not seen what goes on inside present-day higher education.

A while ago I went back to college with my daughter. Aside from some summer in-service training in the Theological Seminary at Princeton in buildings and under conditions which change little and which her graduates remember with nostalgia, I had not seen what goes on inside present-day higher education.

“Hey, Daddy-o,” said the red-headed light of my life, “how about going to biology with me?”

So promptly at the scheduled hour—although in a large university no one cares whether you come or sleep in—I was seated beside her in an amphitheater that she casually told me could hold between seven and eight hundred. As in most universities, it is full on the first day of each semester and then the intellectual death rate begins to take its toll. This day there were probably no more than six hundred, which is still larger than most congregations on Sunday morning. The bell, however, was still tolling for them. We sat at long tables that struck us in the chest at the proper height to compel us to stay awake and take notes.

The lecturer, a Ph.D. in biological science, was a woman who is rather a favorite of the students because she relates her material to everyday life. On this first day of classes after the Thanksgiving holiday, the lecture happened to be on the complicated process of digestion. The lecturer reminded the class of the yet undigested cold turkey within them and then plunged immediately into the task at hand, which, like the legendary question to the centipede—“How do you manage with all those legs?”—was calculated to make us so amazed with what was going on inside us that we wouldn’t be able to function properly.

The lecturer had a microphone about her neck; control of the lights in the room and the projector was at the tip of her toes; instead of a blackboard she had in front of her an illuminated writing pad that threw the important words on a screen behind her. But as I sat there, my memory took me back to biology as I had studied it some thirty years before, and I marveled not only at the technology that made the modern classroom itself such an amazing place but also at the amount of detail gathered by biology since I studied it. The list of enzymes in the pancreas alone would drive you mad.

As the lecturer talked rapidly on toward that deadline beyond which no professor dares go lest feet shuffle and books be dropped, two sentences appeared for me on the classroom wall, behind her writings, superimposed on a full-color drawing of the stomach and intestines. They were from Luke 12:55, 56:

And when ye see the south wind blow, ye say, There will be heat; and it cometh to pass. Ye hypocrites, ye can discern the face of the sky and of the earth; but how is it that ye do not discern this time?

The teacher was giving the most convincing testimony to the fact of and the power of and the intent of God I had ever heard. After describing the breakdown of the protein we eat into amino acids and mentioning five or six steps which she said were chemically unfathomable at points, she stated that the food comes to a chemical composition that is “the only composition which would enable the cells to absorb it.” And I wanted to stand up in the midst of a class dedicated to the proposition that evolution makes all things equal and shout that the hand of God was right there in their midst.

Again and again in tracing the biological process the lecturer would arrive at the mysterious end by which all things worked out for good for the turkey dinner and the class. And I thought that even if she could not have shown us a cross section of the soul, she could at least have written across her diagram of the liver, “the work of God.” For the liver, by means of the marvelous ATP, changes glucose into the “only” substance (glucose phosphate) into which it can be transformed and still be used by the body. And parenthetically, it struck me that there is a high degree of correlation between the abuse of the liver, the abuse of the human spirit, and the wages of sin.

But as I looked at the sleepy young faces I knew that they did not see the handwriting. Moreover, I realized that unless the prophet pointed with the eternal pointer to the sovereign God and wrote on the projected cellulose page, “In the beginning God,” they would not know. And it’s a fact, dear reader, that when the lecturer turned off the flow of scientific fact and shut off the lights, I looked at the clock on the back wall and it said five minutes to twelve. - The safety of genetically modified foods.

- Climate change.

- Space exploration.

- The long-term payoffs from government investment in science.

“Our analysis points to only a handful of areas where people’s religious beliefs and practices have a strong connection to their views about science topics and a surprising number of topics where religious differences do not play a central role in explaining their beliefs,” Funk said. “What is most striking is the multiple influences on people’s views.”

People’s opinions are shaped by generational divides, gender, educational attainment, and differences in knowledge about science, she said.

Evangelicals were more likely than the general public to say that humans have not evolved due to natural processes, and that the growing world population will not be a major problem. They were also somewhat likely to favor allowing more offshore drilling and oppose stricter power plant emission limits. They somewhat favor allowing parents to decide what to do about childhood vaccines.

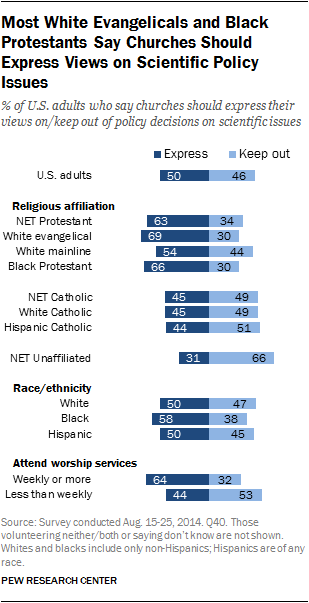

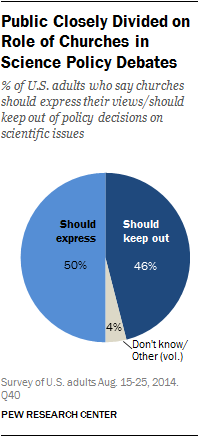

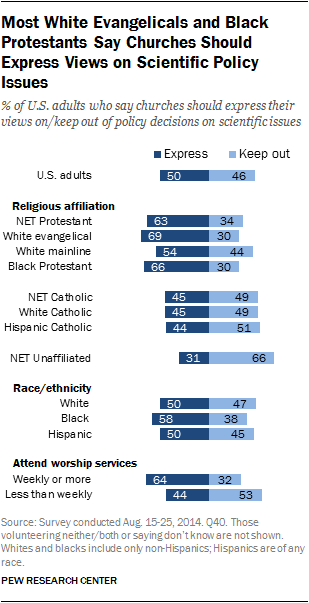

Should religion play a larger role in public opinion on scientific issues? Most evangelicals (69%) and black Protestants (66%) said churches should be guiding views about scientific issues, while the general public is evenly split (50% in favor, 46% opposed) on whether churches should address science from the pulpit.

The latest GSS survey also examined evangelical views on science. The results were mixed.

- One-third (34%) of evangelicals had taken any college-level science course (slightly below the national average of 41%).

- More than half (55%) agreed that science makes our way of life change “too fast.” Most (80%) also said science and technology make our lives better.

- More than two-thirds (69%) said the universe did not begin with a huge explosion (such as the Big Bang), and three-quarters (76%) said human beings did not “develop from earlier species of animals.”

- Overall, about half of Americans (53%) said science is changing our way of life too fast; 82 percent said science is making our lives better. Half said the universe began with an explosion and that humans evolved from animals (53%).

CT’s past reporting on the relationship between science and faith includes extensive coverage of human origins, noting how most Americans—Christian and otherwise—do not fall neatly into creationist or evolutionist camps, how theologians view the debate, and how debates help (or hurt) the discussion.

[Image courtesy of Steve Rainwater – Flickr]