In this series

In this analysis, CT theology editor Caleb Lindgren compares Ligonier’s 2018 theology survey to the 2016 version, followed by ten expert reactions to the overall results.

Are American Christians really this bad at theology? Are we simply just a band of unwitting heretics? Ligonier Ministries and LifeWay Research’s recent State of Theology study seems to indicate that, yes, a large percentage of us are.

While it may be tempting to declare a state of theological emergency, a further look at the groundbreaking survey, now in its third wave, shows room for optimism amid the concern.

Clearly the theological acuity of Christians in the United States could improve. But the findings from Ligonier’s study actually indicate that where instruction and education do occur, at least evangelicals can be remarkably orthodox. By comparing this year’s study and the previous one from 2016, we can gain a better idea of what these results say about how heretical we American Christians are.

Let’s focus on evangelicals by belief, as defined by the National Association of Evangelicals, and start with the questions that were reworded between the 2018 study and the 2016 study.

In 2016, the survey phrased one question as, “People have the ability to turn to God of their own initiative,” and about 8 in 10 respondents agreed (82%). Compare that to this year’s wording: “Only the power of God can cause people to trust Jesus Christ as their savior,” which garnered an essentially identical agreement of 83 percent. So between 2016 and 2018, nearly the same percentage of evangelicals believed diametrically opposed positions on the very same issue. (To be fair, the Council of Orange in A.D. 529, which attempted to clarify this matter, struggled with just this question. But church leaders ultimately kept the initiative solely in God’s hands.)

In a question on faith and works, the 2016 version states, “My good deeds help me earn my place in heaven,” to which 39 percent of evangelical respondents agreed. This year’s wording reverses the emphasis: “God counts a person as righteous not because of one's works but only because of one's faith in Jesus,” to which 91 percent agreed. That’s a 30 percentage point swing, when you account for the opposite wording.

Again, different phrasing yields very different—and more orthodox—results. One explanation: In both cases, the newer wording sounds much more like standard confessional statements evangelicals would be familiar with. Also, the 2018 versions allow respondents to agree with an orthodox statement rather than disagree with a heterodox one. As church history shows us again and again, it’s much easier to agree with orthodoxy than to identify heresy.

Occasionally, the study used a clearer wording and yielded different results. For instance, the prosperity gospel saw an uptick in popularity of 9 percentage points off the back of more specific wording (additions in italics): “God will always reward true faith with material blessings in this life” (46% of respondents agreed). Likewise, there was a drop of 24 percentage points of people who think political engagement is a problem as long as it is “Christians” doing it, rather than “the church.”

In cases where the wording remained the same, the study found slightly more evangelical respondents departing from the historic doctrines of Christianity than in 2016, but there were also a few new questions in this year’s survey that provide food for thought and even some encouragement.

In the 2018 survey, high numbers affirmed that “sex outside of marriage is a sin” (89%), and “abortion is a sin” (88%). And though nearly all evangelicals (99%) agreed with the statement, “God created male and female,” 30 percent of evangelicals said that “gender identity is a matter of choice.”

Likewise, while the majority of evangelicals hew to the traditionalist perspective on homosexuality, 1 in 5 agreed that “the Bible's condemnation of homosexual behavior doesn't apply today.” Yet all 581 of the evangelical respondents in the survey had to strongly agree that “the Bible is the highest authority for what I believe” to be classified as “evangelical by belief.”

Another new question stated, “the Holy Spirit can tell me to do something which is forbidden in the Bible,” to which 21 percent of evangelicals agreed. Theologians weighed in on confusion about the Holy Spirit following the the 2016 study.

Lastly, while hell and judgment are very unpopular in the general culture, evangelicals are sticking with Scripture: 93 percent believe that “hell is a real place where certain people will be punished forever,” and 98 percent agreed that “there will be a time when Jesus Christ returns to judge all the people who have lived.”

CT also asked ten scholars to explain what they find most discouraging and encouraging about Ligonier’s 2018 State of Theology survey:

Timothy Larsen, professor of Christian thought, Wheaton College:

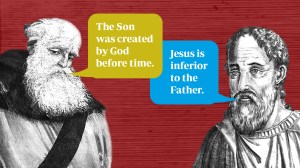

I found these results encouraging. Most Americans often hold orthodox beliefs. Even the Arian heresy is just people wanting to praise Jesus and getting distracted by the superlative “greatest.” If asked, most would have agreed that “Jesus is truly God.”

One piece of good news for evangelicals was that they were more likely than Catholics or mainline Protestants to disagree with, “Worshiping alone or with one’s family is a valid replacement for regularly attending church.” The charge that individualism is a particular problem for evangelicalism has been overplayed.

The black community is noticeably more orthodox, so clearly white believers need to start learning from African Americans how to do effective discipleship.

Most surprising was that 18- to 24-year-olds are sometimes more conservative than those over 65, including on abortion, hell, and the priority of evangelism.

One discouragement was that regular churchgoers were more likely to deny the personhood of the Holy Spirit. Many churches are doing a poor job of teaching pneumatology.

Fred Sanders, professor, Torrey Honors Institute, Biola University:

This survey indicates that what is at work in many Christians is “zeal without knowledge.” The dead giveaway is the number of people who agreed with the statement, “Jesus is the first and greatest being created by God.”

To venture a guess at what was going through their minds, they heard positive, complimentary words about Jesus (“Jesus … first … greatest … God”) and said a hearty Amen. I suspect they were trying to indicate a high opinion of him, and responding largely in terms of an attitude of general affirmation of anybody saying good things about Jesus.

It’s touching to see them try to praise Jesus this way. But it’s mostly disheartening, because it indicates such a low level of theological formation that they couldn’t tell they were doing the opposite of what (if I’m right) they intended. The need for some form, almost any form, of catechizing is acute.

Kristen Deede Johnson, professor of theology and Christian formation, Western Theological Seminary:

At first I was encouraged by the number of evangelicals who still believe that the cross of Christ is essential for addressing sin. Pondering it further, I realized that this finding highlights the troubling separations that exist between theology and discipleship. Comparing this finding to others in the survey on such things as how we understand the Holy Spirit and the importance of the local church, I was reminded that we as evangelicals often struggle to see how theology connects to our ongoing lives of discipleship—to everything that happens after our salvation.

Thinking of my own story, while I am deeply grateful for the ways a local high school youth group invited me to encounter the saving grace of Christ, it took another 10 years for me to encounter theology and understand its significance for my daily life in Christ. Today when I teach courses on discipleship, I dedicate huge chunks of these classes to theology. I am continually amazed at what occurs: as the Holy Spirit refines our theological convictions in light of Scripture, we are drawn more deeply into the life-giving grace of our Triune God and prepared more fully to seek first His Kingdom and righteousness.

John Stackhouse, professor of religious studies, Crandall University:

The survey sounds a legitimate and important warning. If people fundamentally misunderstand basic Christian theology, they cannot convert to it or practice it but instead will be literally following a different religion. Strangely, however, the survey combines what would be globally, ecumenically understood as crucial doctrine with oddly put questions that may not be eliciting good data. For instance, faithful Christians actually disagree about the interplay of God’s finely grained guidance and human responsible freedom in “day-to-day decisions.” Does God really care what socks you wear or whether you order in Chinese or Thai food for supper? Maybe, maybe not. Does the smallest sin warrant eternal damnation? I can’t think of a major theologian who speaks to that weird hypothetical when the overwhelming reality is that we all are sinful, and that’s the reality the Bible does address. I can see even pretty orthodox people giving different answers here.

In short, though, I agree that the teaching task remains critical. And those of us who teach the church’s teachers need to do a better job of helping pastors teach good doctrine, demonstrate that that’s what the Bible teaches, and apply it to life so people can see why theology matters.

Aida Besancon Spencer, professor of New Testament (retired), Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary:

I found it encouraging that about one-third of Americans exhibit some key evangelical beliefs with regards to faith, biblical accuracy, and the place of sex in marriage. Although the youth do hold some postmodern beliefs that are not biblical, they lead older adults in being evangelistic, not accepting all religions as true, seeing abortion as sin, all sin deserving punishment, and recognizing the Holy Spirit as the one who gives new birth.

African Americans (as always) lead ethnic groups in agreeing with laudable biblical truths.

I found discouraging that many youth want to be entertained in worship services (46%), that so many evangelicals (78%) think Jesus is the first and greatest being created by God, and that those who attend worship services at least once a month think that the Holy Spirit is a force, not a personal being (66%)—as do many evangelicals (59%).

I found it surprising that the very wealthy are so devout on many questions.

Sung Wook Chung, professor of Christian theology, Denver Seminary:

The most discouraging about these results is that 78 percent of Americans with evangelical beliefs agree that Jesus is the first and greatest being created by God, even though most responses agree that the God of Christianity is uniquely triune. These two beliefs are mutually exclusive. Arian heresy has returned!

Another very discouraging aspect of the survey is that a majority of responses agree the Holy Spirit is an impersonal force and most people are good by nature. If most people are good, why do they need salvation?

In contrast, the most encouraging part of the survey results is that 97 percent of Americans with evangelical beliefs agree that biblical accounts of the physical (bodily) resurrection of Jesus are completely accurate and this event actually occurred. This means that most evangelicals are still committed to the supernatural character of Christianity. As a corollary, most Americans with evangelical beliefs (83%) agree that Jesus is the only savior of sinners. This is encouraging!

B. J. Oropeza, professor of biblical and religious studies, Azusa Pacific University:

There is one true God in three persons (God the father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit) receives the best percentage with 97 percent of Americans with evangelical beliefs agreeing, in keeping with the early Christian creeds. It is ironic, then, that the Arian view that “Jesus is the first and greatest being created by God,” a view the writers of these same creeds opposed, also received the best percentage with 78 percent of Americans with evangelical beliefs agreeing.

Moreover, 57 percent of evangelicals say that “the Holy Spirit is a force but is not a personal being.” How, then, could he be “God” and a “person” if an impersonal force? Obviously, quite a number of those surveyed do not fully understand what they think they believe.

M. Sydney Park, associate professor of divinity, Beeson Divinity School:

The troubling results of the survey only confirm what many have suspected for years as evangelical churches seek to mark their relevance for contemporary culture increasingly along the lines of sociology and psychology, rather than theology. Clearly, renewed commitment to teach Scripture will directly redress the various points of theological confusion; and with equal clarity, such theological reinforcement will result in rejection and dissociation for many.

The results of the survey, however, call for a deeper self-analysis, which requires something more than simply robust pedagogy. In what significant ways does the evangelical church demonstrate the advantage of orthodoxy, particularly, in contrast to the prevalent culture of relativism and self-actualization? Resurgence of theological teaching alone cannot ultimately resolve the crisis. Without demonstrable evidence of the benefits and consequence of the cross, the testimony of evangelical churches remains emaciated, without power to effectively challenge the countervailing cultural trend and ethos.

Elizabeth Rios, founder, the Passion Center; vice president, Plant4Harvest:

What I see from this survey is that much of Bebbington’s four evangelical core convictions are still held on to “on paper” by American evangelicals. It is encouraging to read that in regards to biblicism, there is a high percentage of evangelicals who still believe in the final authority of the bible for how they believe and behave, yet confusing because of the way they actually are behaving in America. It is encouraging to read that there are still a high percentage of American evangelicals who believe in not staying silent when it comes to politics. But troubling because what some evangelicals are saying when they do speak up in politics is so antithetical to what Jesus actually modeled. And finally, it is discouraging to read that almost half of American evangelicals believe that God will always reward "true faith" with material blessings. Yet it explains why most white evangelicals are much more predisposed to believe it's your own fault if you're poor and support policies that further drive home this belief. On paper, everything looks “normal” but in the real world, we all can see that it is an entirely different reality.

Christopher Hall, distinguished professor of theology emeritus, Eastern University:

Ninety-three percent of evangelicals agreed that God is indeed triune in nature. However, my own experience when I taught theology at Eastern University, and often in evangelical churches, indicates that while evangelicals attest the doctrine of the Trinity to be true, they don’t understand clearly what the doctrine teaches about God. I would estimate that 97 percent of my students were predictably heretical when they tried to explain the Trinity to me in such ways as, “the Father is part of God, the Son is part of God, the Holy Spirit is part of God.” Or I would run into illustrations of the Trinity where shamrocks or water, ice, and mist were used.

Perhaps ironically, this problem relates to evangelicals being Bible people. They learn the Bible every Sunday—something I encourage—but when they step out into what the Bible teaches about the Trinity or the Incarnation, most evangelicals end up stuck. They simply haven’t been catechized well. Most haven’t studied much church history or historical theology. In some ways, evangelical confusion on one question, “Jesus is the first and greatest being created by God,” illustrates my point. Seventy-eight percent agree with Arius—the arch-heretic of the fourth century. Quite shocking. The church fathers wouldn’t be pleased.

I am encouraged by evangelical commitments to the Scripture, opposition to the taking of innocent life, and clarity on human sexuality issues.