Black Americans remain more religious than other Americans, according to a massive new survey. Yet fewer are attending or seeking out predominantly black churches.

Among black worshipers:

- 4 in 10 now attend a non-black congregation—including half of millennials and Gen Z.

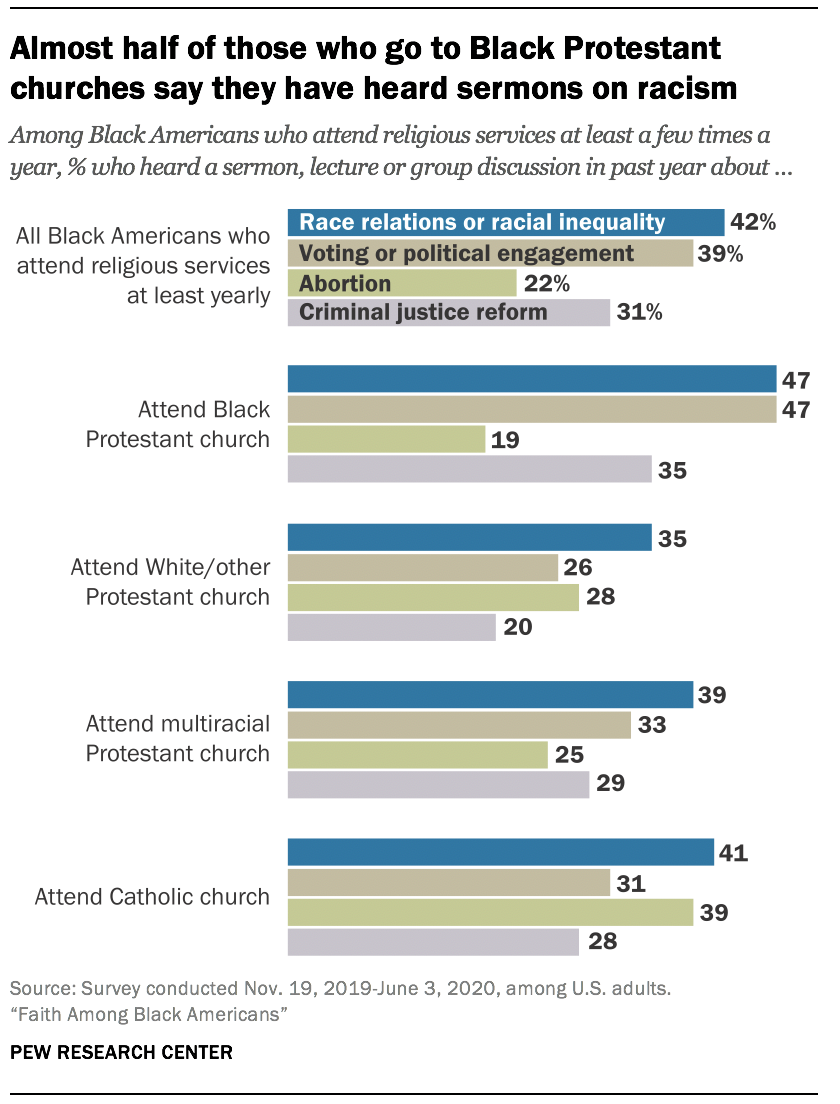

- About half say it’s essential for churches to offer “racial affirmation or pride,” while only a quarter say sermons on political topics are essential.

- 6 in 10 say black congregations should diversify.

- 6 in 10 say when church shopping, finding a congregation where most attendees share their race is unimportant.

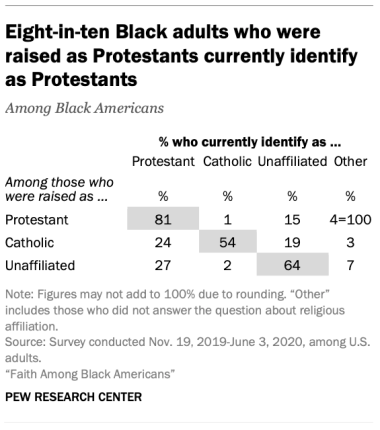

Two-thirds of black Americans identify as Protestants, but only 1 in 4 of these identify with historic black denominations.

Yet retention is strong: 3 in 4 black adults have the same religious affiliation as when they were raised (significantly higher than the rate for Americans at large), while 1 in 4 black Americans who were raised as unaffiliated or as Catholic now identify as Protestant.

These are among the findings of “Faith Among Black Americans,” released today by the Pew Research Center. The study is Pew’s “most comprehensive, in-depth attempt to explore religion among Black Americans” ever, comprising both a national survey of 8,660 adults who identify as black or African American as well as guided small-group discussions and interviews with clergy.

“Many findings in this survey highlight the distinctiveness and vibrancy of Black congregations, demonstrating that the collective entity some observers and participants have called ‘the Black Church’ is alive and well in America today,” stated Pew researchers.

“But there also are some signs of decline, such as the gap between the shares of young adults and those in older generations who attend predominantly Black houses of worship.”

The fact that the black church isn’t declining as fast as the white church is not cause for celebration, says Mark Croston, national director of black church partnerships for LifeWay Christian Resources.

“An 81 percent retention rate may be a good number in business, but not for the church,” he said. “The gospel is relevant and needed in every generation. We have to make sure we are ministering it in ways that will cause it to connect with people we are missing.”

Sider and North spar over issue at Gordon-Conwell Seminary.Should Christians be pushing civil government to take an active role in the reduction of worldwide poverty? Two Christian scholars met April 6 at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in South Hamilton, Massachusetts, to debate the biblical evidence of civil government’s role in relief of the poor.Ronald J. Sider, author of Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger and professor of theology and ethics at Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Philadelphia, charged that the biblical concept of justice demands that Christians work politically to break down the structural causes of poverty. Gary North, president of the Institute for Christian Economics and a staff member of the Chalcedon Foundation, agreed Christians do have a duty to feed the poor. But he argued that efforts should be made through the church, not civil government.Sider laid out the biblical foundation for the argument that Christians should be concerned for the poor; North agreed with his main point.The two men were far from agreement, however, on the critical question of what all that means to the church today. Sider argued that while charity and volunteerism are necessary, they are not enough in themselves. According to the prophets, he said, it is not just the individual poor person God is concerned with; it is also the social system that contributes to his poverty.The prophets Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Isaiah, and others condemn the rich for either gaining wealth by oppression and treachery or for turning a deaf ear to the cries of the poor, Sider said. God never intended there to be a wide social gap between rich and poor, he contended. The jubilee concept laid down in Leviticus is proof that “God does not want such a disadvantage.” When the Hebrews first occupied the land of Canaan, God divided the land equally, and “he wanted that arrangement to remain and to continue,” said Sider, to be sure every person “had an equal share in and means of providing wealth.” The legal return of land every 50 years to its original owner insured that equality, he noted.The jubilee underlines the biblical basis for an “institutionalized mechanism” for the relief of poverty “rather than haphazard handouts by wealthy philanthropists,” Sider claimed. The Christian’s duty then, he said, is to “demand that civil government design programs” to provide the poorer members of society with the resources they need to earn their fair share of the wealth.But North charged that the state cannot be trusted with the task of reducing poverty. Confessing he held the Puritan view in a four-centuries-old debate between Puritans and Anabaptists on this issue, North cited atrocities in American history as proving foreign aid often “leads to imperialism internationally.” Money sent to help the poor in the fields, he said, is used instead to build up urban complexes 40 stories high and to create large bureaucracies (e.g., the Bureau of Indian Affairs) where government employees end up absorbing the money intended for the poor.When Old Testament prophets came upon nations that had strayed from God’s standard, they directed rulers back to the law. The church today must do likewise, North stated. “Christians are to serve as salt,” and, he said, salt had two purposes in Bible times: it was used for flavoring and for destruction. “If we do our task well,” said North, “we’re going to replace the prevailing civil order.” Then Christians can establish a new government that would be “unquestionably geared to justice.”Meanwhile, the church is to be a model to the nation in working for the relief of the poor and hungry. Christians should tithe a tenth of their income and a portion of that should go to the alleviation of poverty.But Christians need to be freed from the tyranny of taxation so they can give more freely to charity, North continued. “And the Bible has just the solution. 1 Samuel 8 sets a limit on the amount the state can tax its people according to God’s law, at 10 percent; and that is how it should be done today.”North also challenged the idea that redistribution of the wealth would benefit the poor for more than one or two years and charged the motivating force of its proponents is envy. Envy, or “tearing down the rich just to get even,” he said, originated with Satan.Many Christians today feel guilty for having wealth, but if they are tithing, they have no reason to feel guilty, North stated. “If Christians began to tithe, they would change the face of the earth.” God blesses those who follow his law, and his law demands giving 10 percent of one’s earnings to God’s work.But the models North chose to illustrate this point raised a few eyebrows among his audience of 200 seminarians and professors. He praised the Mormons for building churches without going into debt, and Herbert Armstrong’s Worldwide Church of God for its obedience to the required tithe. Of Armstrong’s church, North said, “Look at the blessings God has given to that church. It’s incredible.”In his summary, Sider said Christians should use “reasoned, intelligent analysis” to make social changes “in light of what the Bible says we should be doing.” But North disagreed. He argued the Bible indeed is specific, and that what was good enough for the Old Testament prophets is good enough for him.The Legislative SceneAbortion Factions Skirmish Over Koop AppointmentCongressional supporters of C. Everett Koop are confident they can overcome a legislative roadblock that is threatening his appointment as U.S. surgeon general. Koop, chief surgeon at Philadelphia’s Children’s Hospital, is a well-known evangelical. Those who oppose him are doing so because of his strong stands against abortion and homosexuality, and they have found a technicality to use against him.The technicality is that Koop, 64, is six months over the age limit for the surgeon general’s job, making it necessary to pass a bill exempting him. Sen. Jesse Helms (R-N.C.) attached the legislation onto an unrelated bill (dealing with credit cards), and the Senate passed it. When it got to the House, however, Speaker Thomas P. O’Neill (D-Mass.) found an obscure procedure to strip the amendment and deposit it in the House Health and Environment Subcommittee.The chairman of that subcommittee is Henry Waxman (D-Cal.), one of the sponsors of a national gay rights bill, who differs with Koop’s conservative positions. Waxman called a subcommittee hearing to open a broad-range attack on Koop, and was further annoyed when Koop did not appear to defend himself. Waxman said last month that “Dr. Koop frightens me. He does not have a public health background, he’s dogmatically denounced those who disagree with him, and his intemperate views make me wonder about his and the administration’s judgment.”There was plenty of opposition to Koop at Waxman’s hearing. A spokesman for the American Public Health Association said that although Koop was “a distinguished pediatric surgeon,” he was untrained in public health. A spokesman for the National Gay Health Coalition said, “Koop appears to have strongly held beliefs about homosexuality which are not supported by established medical thought, practice, or science.” A spokesman for a women’s proabortion group also criticized him.Because the House passed the credit-card bill without the age exemption for Koop (as well as five other amendments the Senate added to the bill), a House-Senate conference committee, composed of members of both houses, will meet to reconcile the differences. Koop supporters hope the age exemption will be put back during the conference; if not, they have another strategy. Rep. Henry Hyde (R-Ill.) has introduced the age exemption as a separate bill. Although it has also been sent to Waxman’s subcommittee. Koop partisans hope to use a discharge petition to spring it out of the subcommittee directly to the House floor, where they believe it would pass easily. The discharge petition, however, is a cumbersome procedure that does not usually work.Carl Anderson, an assistant to Senator Helms, said, “We’ll do whatever has to be done to get this thing.Mennonites after SmoketownA Call To Move Beyond The Peace Issue To EvangelismSignals keep coming from Smoketown. This was observable at a recent Mennonite gathering in Berne, Indiana, where some 200 pastors and lay leaders talked and prayed about restoring the Mennonite tradition to a firm evangelical footing.They reaffirmed most of the concerns coming out of the so-called Smoketowr Consultation two years ago (held in Smoketown, Pennsylvania): reaffirmatior of the authority of Scripture, need for renewed evangelistic emphasis, and a reexamination of priorities, with the emphasis on the saving power of the gospel.A five-member convening group (four of them pastors) planned this second inter-Mennonite meeting, or “Consultation or Continuing Concerns,” as a way to spreac the vision of the earlier one, and to share new concerns. The meeting, in the Berne First Mennonite Church, was open to anyone, whereas Smoketown was a small, by-invitation-only gathering of about 20 pastors, educators, and lay leaders.A general feeling underlying both meetings was that Mennonite bodies have overemphasized their historic peace and social emphases at the expense of evangelism and discipleship, among other things. Several well-known Mennonite leaders echoed this in Berne, and touched on the broader issue of secularism. Some spoke to the grassroots criticism that Mennonite colleges have lost accountability to the local churches, and are being affected by liberalism.Albert Epp, Henderson, Nebraska, pastor who, with host pastor and fellow convener Kenneth Bauman of Berne serve the two largest congregations in the 60,000-member General Conference Mennonite church, opened the two-day session with a devotional, pointing out the power of prayer at Pentecost.When people become affluent or educated, warned Epp, one of the first casualties is prayer. “We have not because we ask not. Prayer can rescue the Mennonite brotherhood from shipwreck. The Holy Spirit can do in a minute what you and can’t do in a lifetime.”Theologian Myron S. Augsburger, immediate past president of Eastern Mennonite College and presently a scholar-in-residence at Princeton Theological Seminary, was concerned that “academic and cultural pseudo-sophistication not rob us of the freedom to share Christ.” Later in the meeting, speaker Benjamin Sprunger, past president of Bluffton (Ohio) College, was asked what he sees as the redeeming factor for the Mennonite church. He responded: “The Scripture speaks for ancient times, present times, and future times. Out of that presupposition we must find our way and not let that get diluted by secular and contemporary thought. We cannot ignore psychology, sociology, and science, but we cannot let those replace God’s Word.”In the third major address, moderator Vernon Wiebe of the Mennonite Brethren church praised his denomination for being “unashamedly evangelical and Anabaptist.” He noted, however, that sometimes “we have been afraid to join together in spiritual exercises. We are comfortable with relief sales, but not the study of the Word.”Eugene Witmer of Smoketown chaired the findings committee, which arrived at a list of 15 concerns. Witmer, also a convener of the Berne meeting, cited in an interview “sharp lines” of concern that prompted the meeting—for instance, the desire to address Mennonites “who place so much attention on the peace issue, but are strangely silent on abortion and alcoholism.”Conveners said attendance was about 150 percent better than expected, with many persons coming at their own expense. In many respects, the meeting mirrored developments in other denominations, where conservatives are trying to restore traditional, evangelical emphases.North American SceneParents of John W. Hinckley, Jr., the man charged with the presidential assassination attempt, made a Christian commitment in 1978. Since then they have given heavily to overseas relief and development projects, including those of World Vision. Jack Hinckley is a water resources consultant for World Vision, and reportedly had expressed concern about his son to some of the organization’s staff and requested special prayer for him.Called a devout fundamentalist Christian by acquaintances, Edward Michael Richardson, 22, of New Haven, Connecticut, was indicted last month on two counts of threatening the life of President Reagan. Federal investigators were checking similarities between Richardson’s alleged threats and a letter received by TV evangelist Jimmy Swaggart. He turned over to the FBI a note he received March 25 with the message scrawled on the back of a ministry fund-raising envelope: “Ronald Reagan will be shot to death and this country turned back to the left.”An interfaith forum was organized last month in Jefferson City, Missouri, with some observers calling it a new breakthrough for interfaith relations. Missouri leaders of 11 Protestant denominations, and four Roman Catholic bishops, announced formation of the so-called Missouri Christian Leadership Forum. Its purpose will be dialogue and possible cooperation on mutual concerns, such as issues before the Missouri legislature. The forum includes groups such as the Missouri Baptist Convention, and Catholics. The latter had refused membership in the Missouri Council of Churches, which they saw as too liberal and structured.Groups have a constitutional right to pass out literature at airports without notifying authorities in advance. So ruled the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals last month. The court called unconstitutional a Portland, Oregon, ordinance that required groups to give one day’s notice before picketing or distributing literature at the city’s airport, and to provide names, addresses, and telephone numbers of those sponsoring the distribution. The decision reversed a U.S. District Court ruling upholding the ordinance, which was challenged by Jews for Jesus chairman Moishe Rosen. He had been arrested for violating the ordinance while distributing literature at the Portland terminal.A week of prayer emphasizing a call to national confession of sin and repentance is scheduled May 31 to June 7 as a prelude to this summer’s American Festival of Evangelism in Kansas City, Missouri. Festival spokesman Norval Hadley explained, “We are urging Christians to unite in prayer for America. We want God to help us see our condition as he sees it.” Hadley suggested churches provide opportunities for organized prayer during the week: prayer groups, prayer with sister churches, prayer partners, 24-hour prayer and fasting chains, and so on. The prayer week culminates on Pentecost Sunday, the day designated for the annual prayer effort for world evangelization sponsored by the Lausanne Comittee for World Evangelization.PersonaliaWar hero and sportsman Joe Foss was appointed international chairman of the billion-dollar evangelization campaign, Here’s Life, World, sponsored by Campus Crusade for Christ International. Foss, a Congressional Medal of Honor recipient during World War II and the first commissioner of the old American Football League, succeeds Wallace E. Johnson, cofounder of Holiday Inns, who asked to be relieved after suffering a mild heart attack last fall.Asia missions veteran Samuel H. Moffett, 65, accepted a three-year appointment as professor of ecumenics and mission at Princeton Theological Seminary. Moffett currently is vice-president of Presbyterian Seminary in South Korea, and a long-time missionary there. He has spent the last several years doing research for a book that will chronicle the history of the Christian church in East Asia.Academia: Ronald Youngblood, dean of Wheaton College Graduate School, has resigned and will join the Old Testament department at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Deerfield, Illinois, next fall; James Plueddemann, chairman of the school’s Christian ministries department, was named acting dean effective July 1. Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary profesor David M. Scholer, Wheaton College and Harvard Divinity School trained, was appointed dean at 200-student Northern Baptist Theological Seminary near Chicago, succeeding Gerald Borchert, now at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.World SceneFour out of fifteen Protestant churches in Lyon, France, have been destroyed by arson this year. The latest, a Pentecostal assembly structure that seated more than 500, was set ablaze in the early morning hours of Sunday, March 29. An outdoor baptismal service to have been held on the premises had been publicized for that evening. After the three January burnings, police increased surveillance of the evangelicals’ properties. So far they have no suspects in the acts of destruction, which evidence a common pattern of sabotage.Pope John Paul II will visit World Council of Churches headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, next month. The June 5 visit to Philip Potter, WCC general secretary, and other council officials is the second papal visit. Pope Paul VI paid a visit to the ecumenical center in 1969.The Helsinki follow-up conference in Madrid has failed to inhibit Soviet authorities in oppression of religious believers. Orthodox priest Gleb Yakunin’s appeal of his 10-year sentence has been rejected, and presumably he has been transported from prison to a labor camp. Boris Perchatkin, a spokesman for the Pentecostal emigration movement who contacted foreign journalists in Moscow, has been sentenced to two years of labor. Eight Baptists arrested last June while operating a clandestine printing press have received sentences ranging from three to five years each, and the press has been confiscated. Keston College also reports sentences for five other believers.One in every two refugees in the world today is African. This shift may come as a surprise to many who grew accustomed to associating “refugee” with Southeast Asian “boat people.” Poul Hartling, the United Nations high commissioner for refugees, points out that Africa, with only 12 percent of the world’s population, has almost 50 percent of its refugees—some five million. Four out of five African refugees have found asylum in countries that are themselves among the least developed in the world. Host countries, says Hartling, have responded with traditional African hospitality. “The problem,” he says, “is that their hospitality is being offered from an empty table. Help from outside is crucial.”An official Protestant delegation from China took part in an Asian Christian consultation in Hong Kong last month. It was the first such visit outside the People’s Republic since the Communist takeover 32 years ago. The delegation was headed by Bishop Ding Guanxuan (K. H. Ting), president of the China Christian Council and chairman of the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (CT, Jan. 2, 1981, p. 46). Among Ding’s statements, as reported in the South China Morning Post:Only a minority of Chinese are Communists and the majority are both patriotic and theistic. Even though currently unable to meet the demand, the TSPM will not accept help in making Bibles available. The movement’s long-term policy, he said, is to enable every Protestant to own a copy of the Bible, many of which were burned during the cultural revolution. Religious broadcasts into China not approved by the TSPM would be considered unfriendly.

Sider and North spar over issue at Gordon-Conwell Seminary.Should Christians be pushing civil government to take an active role in the reduction of worldwide poverty? Two Christian scholars met April 6 at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in South Hamilton, Massachusetts, to debate the biblical evidence of civil government’s role in relief of the poor.Ronald J. Sider, author of Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger and professor of theology and ethics at Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Philadelphia, charged that the biblical concept of justice demands that Christians work politically to break down the structural causes of poverty. Gary North, president of the Institute for Christian Economics and a staff member of the Chalcedon Foundation, agreed Christians do have a duty to feed the poor. But he argued that efforts should be made through the church, not civil government.Sider laid out the biblical foundation for the argument that Christians should be concerned for the poor; North agreed with his main point.The two men were far from agreement, however, on the critical question of what all that means to the church today. Sider argued that while charity and volunteerism are necessary, they are not enough in themselves. According to the prophets, he said, it is not just the individual poor person God is concerned with; it is also the social system that contributes to his poverty.The prophets Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Isaiah, and others condemn the rich for either gaining wealth by oppression and treachery or for turning a deaf ear to the cries of the poor, Sider said. God never intended there to be a wide social gap between rich and poor, he contended. The jubilee concept laid down in Leviticus is proof that “God does not want such a disadvantage.” When the Hebrews first occupied the land of Canaan, God divided the land equally, and “he wanted that arrangement to remain and to continue,” said Sider, to be sure every person “had an equal share in and means of providing wealth.” The legal return of land every 50 years to its original owner insured that equality, he noted.The jubilee underlines the biblical basis for an “institutionalized mechanism” for the relief of poverty “rather than haphazard handouts by wealthy philanthropists,” Sider claimed. The Christian’s duty then, he said, is to “demand that civil government design programs” to provide the poorer members of society with the resources they need to earn their fair share of the wealth.But North charged that the state cannot be trusted with the task of reducing poverty. Confessing he held the Puritan view in a four-centuries-old debate between Puritans and Anabaptists on this issue, North cited atrocities in American history as proving foreign aid often “leads to imperialism internationally.” Money sent to help the poor in the fields, he said, is used instead to build up urban complexes 40 stories high and to create large bureaucracies (e.g., the Bureau of Indian Affairs) where government employees end up absorbing the money intended for the poor.When Old Testament prophets came upon nations that had strayed from God’s standard, they directed rulers back to the law. The church today must do likewise, North stated. “Christians are to serve as salt,” and, he said, salt had two purposes in Bible times: it was used for flavoring and for destruction. “If we do our task well,” said North, “we’re going to replace the prevailing civil order.” Then Christians can establish a new government that would be “unquestionably geared to justice.”Meanwhile, the church is to be a model to the nation in working for the relief of the poor and hungry. Christians should tithe a tenth of their income and a portion of that should go to the alleviation of poverty.But Christians need to be freed from the tyranny of taxation so they can give more freely to charity, North continued. “And the Bible has just the solution. 1 Samuel 8 sets a limit on the amount the state can tax its people according to God’s law, at 10 percent; and that is how it should be done today.”North also challenged the idea that redistribution of the wealth would benefit the poor for more than one or two years and charged the motivating force of its proponents is envy. Envy, or “tearing down the rich just to get even,” he said, originated with Satan.Many Christians today feel guilty for having wealth, but if they are tithing, they have no reason to feel guilty, North stated. “If Christians began to tithe, they would change the face of the earth.” God blesses those who follow his law, and his law demands giving 10 percent of one’s earnings to God’s work.But the models North chose to illustrate this point raised a few eyebrows among his audience of 200 seminarians and professors. He praised the Mormons for building churches without going into debt, and Herbert Armstrong’s Worldwide Church of God for its obedience to the required tithe. Of Armstrong’s church, North said, “Look at the blessings God has given to that church. It’s incredible.”In his summary, Sider said Christians should use “reasoned, intelligent analysis” to make social changes “in light of what the Bible says we should be doing.” But North disagreed. He argued the Bible indeed is specific, and that what was good enough for the Old Testament prophets is good enough for him.The Legislative SceneAbortion Factions Skirmish Over Koop AppointmentCongressional supporters of C. Everett Koop are confident they can overcome a legislative roadblock that is threatening his appointment as U.S. surgeon general. Koop, chief surgeon at Philadelphia’s Children’s Hospital, is a well-known evangelical. Those who oppose him are doing so because of his strong stands against abortion and homosexuality, and they have found a technicality to use against him.The technicality is that Koop, 64, is six months over the age limit for the surgeon general’s job, making it necessary to pass a bill exempting him. Sen. Jesse Helms (R-N.C.) attached the legislation onto an unrelated bill (dealing with credit cards), and the Senate passed it. When it got to the House, however, Speaker Thomas P. O’Neill (D-Mass.) found an obscure procedure to strip the amendment and deposit it in the House Health and Environment Subcommittee.The chairman of that subcommittee is Henry Waxman (D-Cal.), one of the sponsors of a national gay rights bill, who differs with Koop’s conservative positions. Waxman called a subcommittee hearing to open a broad-range attack on Koop, and was further annoyed when Koop did not appear to defend himself. Waxman said last month that “Dr. Koop frightens me. He does not have a public health background, he’s dogmatically denounced those who disagree with him, and his intemperate views make me wonder about his and the administration’s judgment.”There was plenty of opposition to Koop at Waxman’s hearing. A spokesman for the American Public Health Association said that although Koop was “a distinguished pediatric surgeon,” he was untrained in public health. A spokesman for the National Gay Health Coalition said, “Koop appears to have strongly held beliefs about homosexuality which are not supported by established medical thought, practice, or science.” A spokesman for a women’s proabortion group also criticized him.Because the House passed the credit-card bill without the age exemption for Koop (as well as five other amendments the Senate added to the bill), a House-Senate conference committee, composed of members of both houses, will meet to reconcile the differences. Koop supporters hope the age exemption will be put back during the conference; if not, they have another strategy. Rep. Henry Hyde (R-Ill.) has introduced the age exemption as a separate bill. Although it has also been sent to Waxman’s subcommittee. Koop partisans hope to use a discharge petition to spring it out of the subcommittee directly to the House floor, where they believe it would pass easily. The discharge petition, however, is a cumbersome procedure that does not usually work.Carl Anderson, an assistant to Senator Helms, said, “We’ll do whatever has to be done to get this thing.Mennonites after SmoketownA Call To Move Beyond The Peace Issue To EvangelismSignals keep coming from Smoketown. This was observable at a recent Mennonite gathering in Berne, Indiana, where some 200 pastors and lay leaders talked and prayed about restoring the Mennonite tradition to a firm evangelical footing.They reaffirmed most of the concerns coming out of the so-called Smoketowr Consultation two years ago (held in Smoketown, Pennsylvania): reaffirmatior of the authority of Scripture, need for renewed evangelistic emphasis, and a reexamination of priorities, with the emphasis on the saving power of the gospel.A five-member convening group (four of them pastors) planned this second inter-Mennonite meeting, or “Consultation or Continuing Concerns,” as a way to spreac the vision of the earlier one, and to share new concerns. The meeting, in the Berne First Mennonite Church, was open to anyone, whereas Smoketown was a small, by-invitation-only gathering of about 20 pastors, educators, and lay leaders.A general feeling underlying both meetings was that Mennonite bodies have overemphasized their historic peace and social emphases at the expense of evangelism and discipleship, among other things. Several well-known Mennonite leaders echoed this in Berne, and touched on the broader issue of secularism. Some spoke to the grassroots criticism that Mennonite colleges have lost accountability to the local churches, and are being affected by liberalism.Albert Epp, Henderson, Nebraska, pastor who, with host pastor and fellow convener Kenneth Bauman of Berne serve the two largest congregations in the 60,000-member General Conference Mennonite church, opened the two-day session with a devotional, pointing out the power of prayer at Pentecost.When people become affluent or educated, warned Epp, one of the first casualties is prayer. “We have not because we ask not. Prayer can rescue the Mennonite brotherhood from shipwreck. The Holy Spirit can do in a minute what you and can’t do in a lifetime.”Theologian Myron S. Augsburger, immediate past president of Eastern Mennonite College and presently a scholar-in-residence at Princeton Theological Seminary, was concerned that “academic and cultural pseudo-sophistication not rob us of the freedom to share Christ.” Later in the meeting, speaker Benjamin Sprunger, past president of Bluffton (Ohio) College, was asked what he sees as the redeeming factor for the Mennonite church. He responded: “The Scripture speaks for ancient times, present times, and future times. Out of that presupposition we must find our way and not let that get diluted by secular and contemporary thought. We cannot ignore psychology, sociology, and science, but we cannot let those replace God’s Word.”In the third major address, moderator Vernon Wiebe of the Mennonite Brethren church praised his denomination for being “unashamedly evangelical and Anabaptist.” He noted, however, that sometimes “we have been afraid to join together in spiritual exercises. We are comfortable with relief sales, but not the study of the Word.”Eugene Witmer of Smoketown chaired the findings committee, which arrived at a list of 15 concerns. Witmer, also a convener of the Berne meeting, cited in an interview “sharp lines” of concern that prompted the meeting—for instance, the desire to address Mennonites “who place so much attention on the peace issue, but are strangely silent on abortion and alcoholism.”Conveners said attendance was about 150 percent better than expected, with many persons coming at their own expense. In many respects, the meeting mirrored developments in other denominations, where conservatives are trying to restore traditional, evangelical emphases.North American SceneParents of John W. Hinckley, Jr., the man charged with the presidential assassination attempt, made a Christian commitment in 1978. Since then they have given heavily to overseas relief and development projects, including those of World Vision. Jack Hinckley is a water resources consultant for World Vision, and reportedly had expressed concern about his son to some of the organization’s staff and requested special prayer for him.Called a devout fundamentalist Christian by acquaintances, Edward Michael Richardson, 22, of New Haven, Connecticut, was indicted last month on two counts of threatening the life of President Reagan. Federal investigators were checking similarities between Richardson’s alleged threats and a letter received by TV evangelist Jimmy Swaggart. He turned over to the FBI a note he received March 25 with the message scrawled on the back of a ministry fund-raising envelope: “Ronald Reagan will be shot to death and this country turned back to the left.”An interfaith forum was organized last month in Jefferson City, Missouri, with some observers calling it a new breakthrough for interfaith relations. Missouri leaders of 11 Protestant denominations, and four Roman Catholic bishops, announced formation of the so-called Missouri Christian Leadership Forum. Its purpose will be dialogue and possible cooperation on mutual concerns, such as issues before the Missouri legislature. The forum includes groups such as the Missouri Baptist Convention, and Catholics. The latter had refused membership in the Missouri Council of Churches, which they saw as too liberal and structured.Groups have a constitutional right to pass out literature at airports without notifying authorities in advance. So ruled the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals last month. The court called unconstitutional a Portland, Oregon, ordinance that required groups to give one day’s notice before picketing or distributing literature at the city’s airport, and to provide names, addresses, and telephone numbers of those sponsoring the distribution. The decision reversed a U.S. District Court ruling upholding the ordinance, which was challenged by Jews for Jesus chairman Moishe Rosen. He had been arrested for violating the ordinance while distributing literature at the Portland terminal.A week of prayer emphasizing a call to national confession of sin and repentance is scheduled May 31 to June 7 as a prelude to this summer’s American Festival of Evangelism in Kansas City, Missouri. Festival spokesman Norval Hadley explained, “We are urging Christians to unite in prayer for America. We want God to help us see our condition as he sees it.” Hadley suggested churches provide opportunities for organized prayer during the week: prayer groups, prayer with sister churches, prayer partners, 24-hour prayer and fasting chains, and so on. The prayer week culminates on Pentecost Sunday, the day designated for the annual prayer effort for world evangelization sponsored by the Lausanne Comittee for World Evangelization.PersonaliaWar hero and sportsman Joe Foss was appointed international chairman of the billion-dollar evangelization campaign, Here’s Life, World, sponsored by Campus Crusade for Christ International. Foss, a Congressional Medal of Honor recipient during World War II and the first commissioner of the old American Football League, succeeds Wallace E. Johnson, cofounder of Holiday Inns, who asked to be relieved after suffering a mild heart attack last fall.Asia missions veteran Samuel H. Moffett, 65, accepted a three-year appointment as professor of ecumenics and mission at Princeton Theological Seminary. Moffett currently is vice-president of Presbyterian Seminary in South Korea, and a long-time missionary there. He has spent the last several years doing research for a book that will chronicle the history of the Christian church in East Asia.Academia: Ronald Youngblood, dean of Wheaton College Graduate School, has resigned and will join the Old Testament department at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Deerfield, Illinois, next fall; James Plueddemann, chairman of the school’s Christian ministries department, was named acting dean effective July 1. Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary profesor David M. Scholer, Wheaton College and Harvard Divinity School trained, was appointed dean at 200-student Northern Baptist Theological Seminary near Chicago, succeeding Gerald Borchert, now at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.World SceneFour out of fifteen Protestant churches in Lyon, France, have been destroyed by arson this year. The latest, a Pentecostal assembly structure that seated more than 500, was set ablaze in the early morning hours of Sunday, March 29. An outdoor baptismal service to have been held on the premises had been publicized for that evening. After the three January burnings, police increased surveillance of the evangelicals’ properties. So far they have no suspects in the acts of destruction, which evidence a common pattern of sabotage.Pope John Paul II will visit World Council of Churches headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, next month. The June 5 visit to Philip Potter, WCC general secretary, and other council officials is the second papal visit. Pope Paul VI paid a visit to the ecumenical center in 1969.The Helsinki follow-up conference in Madrid has failed to inhibit Soviet authorities in oppression of religious believers. Orthodox priest Gleb Yakunin’s appeal of his 10-year sentence has been rejected, and presumably he has been transported from prison to a labor camp. Boris Perchatkin, a spokesman for the Pentecostal emigration movement who contacted foreign journalists in Moscow, has been sentenced to two years of labor. Eight Baptists arrested last June while operating a clandestine printing press have received sentences ranging from three to five years each, and the press has been confiscated. Keston College also reports sentences for five other believers.One in every two refugees in the world today is African. This shift may come as a surprise to many who grew accustomed to associating “refugee” with Southeast Asian “boat people.” Poul Hartling, the United Nations high commissioner for refugees, points out that Africa, with only 12 percent of the world’s population, has almost 50 percent of its refugees—some five million. Four out of five African refugees have found asylum in countries that are themselves among the least developed in the world. Host countries, says Hartling, have responded with traditional African hospitality. “The problem,” he says, “is that their hospitality is being offered from an empty table. Help from outside is crucial.”An official Protestant delegation from China took part in an Asian Christian consultation in Hong Kong last month. It was the first such visit outside the People’s Republic since the Communist takeover 32 years ago. The delegation was headed by Bishop Ding Guanxuan (K. H. Ting), president of the China Christian Council and chairman of the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (CT, Jan. 2, 1981, p. 46). Among Ding’s statements, as reported in the South China Morning Post:Only a minority of Chinese are Communists and the majority are both patriotic and theistic. Even though currently unable to meet the demand, the TSPM will not accept help in making Bibles available. The movement’s long-term policy, he said, is to enable every Protestant to own a copy of the Bible, many of which were burned during the cultural revolution. Religious broadcasts into China not approved by the TSPM would be considered unfriendly.

Most respondents were surveyed between January 21 and February 10, 2020, before COVID-19 disrupted church life and before protests against police brutality became widespread after the death of George Floyd.

Pew also surveyed 4,574 adults who do not identify as black or African American, in order to draw comparisons.

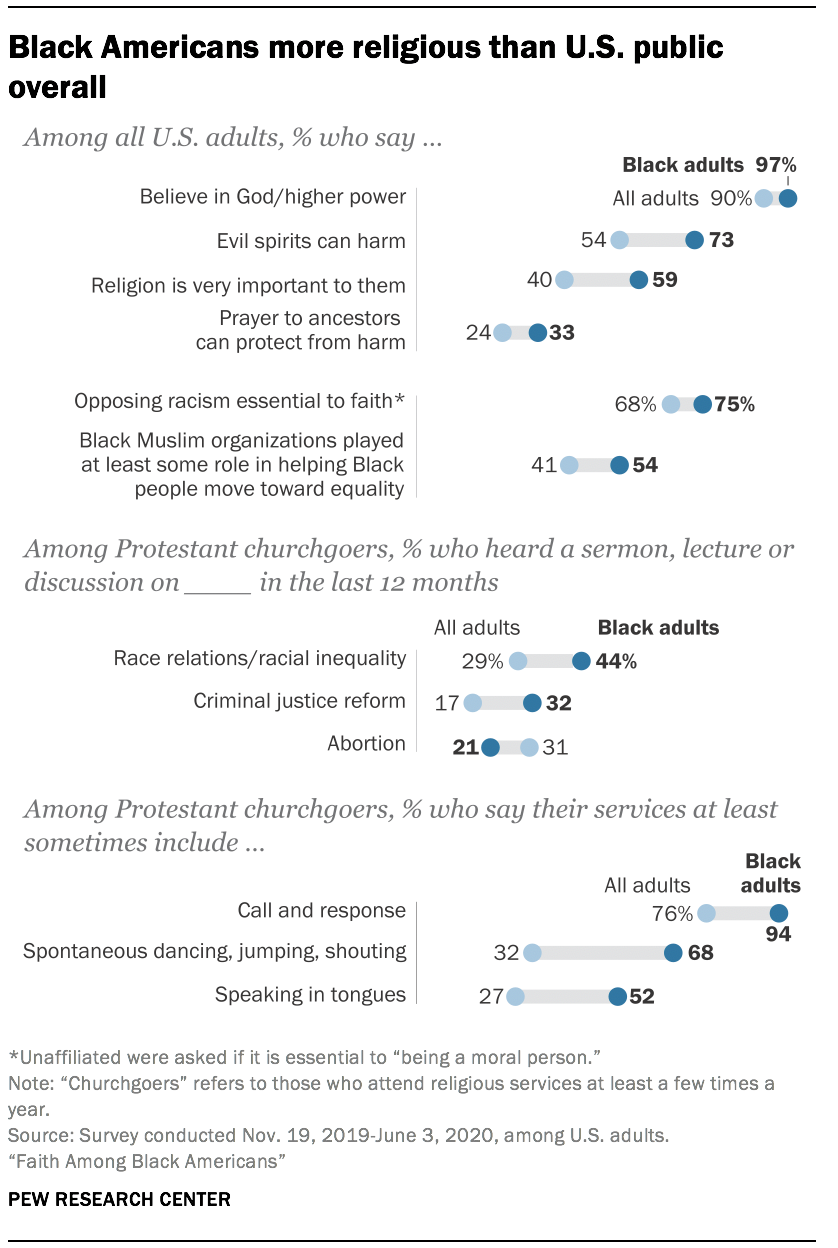

Overall, Pew found that black Americans are more likely than Americans at large to believe in God, attend religious services, say religion is “very important” in their lives, and affiliate with a religion.

Black Americans are:

- More likely to say God talks to them (48% vs. 30%)

- More likely to say they have a duty to convert others (51% vs. 34%)

- More likely to say opposing racism is essential to their faith (75% vs. 68%)

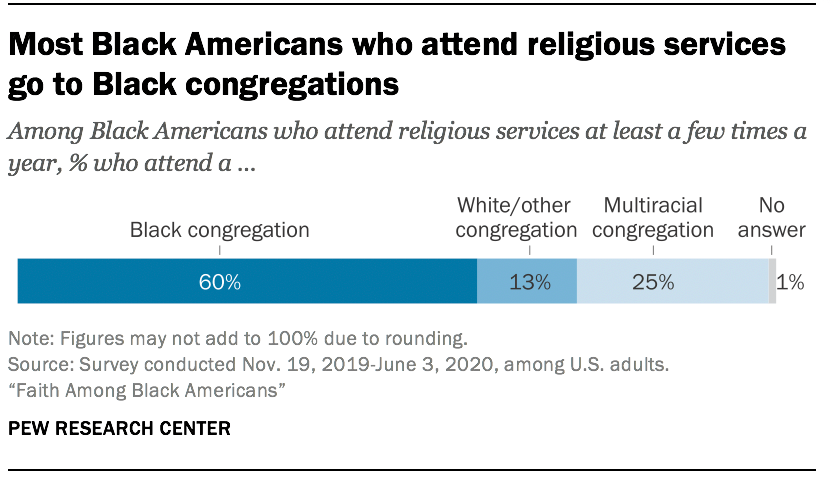

Pew found that 60 percent of black churchgoers attend predominantly black congregations, while 25 percent attend a multiracial congregation and 13 percent attend a predominantly white (or Hispanic or Asian) congregation. Churchgoers who are Protestant were most likely to attend black congregations (67%), vs. those who were Catholic (17%) or of other faiths (29%).

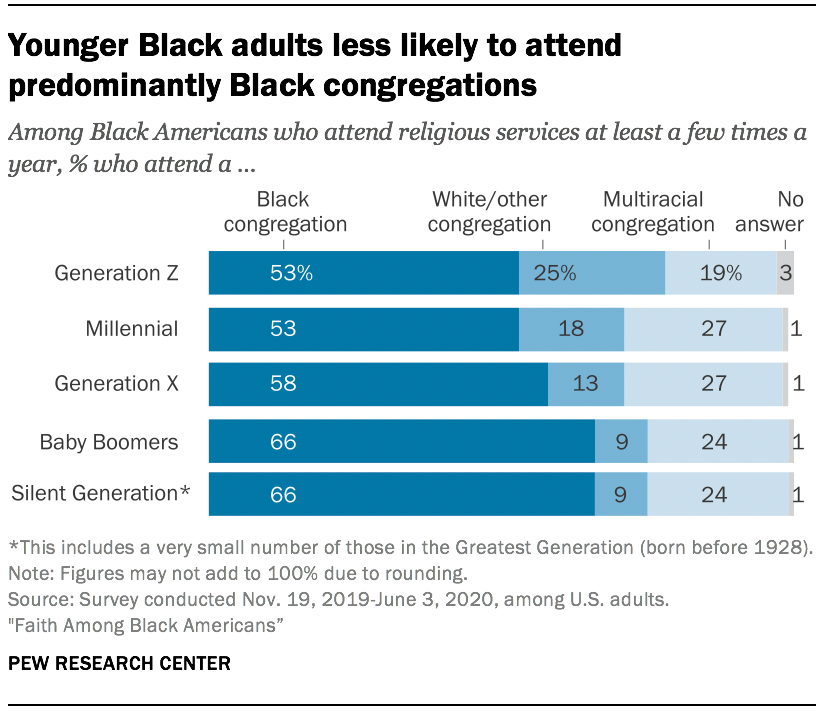

Younger worshipers are less likely to attend black churches than older worshipers. Only half of Gen Z and millennial black worshipers (53%) attend black congregations, vs two-thirds of boomer and older black worshipers (66%). And a full 25 percent of Gen Z black worshipers attend a white (or other) congregation, while only 9 percent of boomers and older black worshipers do likewise.

“One might observe that Black churches have done well with spiritual nurturing the Black community through historic tough times and with fighting social and political injustice but not as well with pursuing an ecclesial vision for racial/ethnic inclusion,” said Antipas Harris, the president of Jakes Divinity School. “As a result, more white-led, multicultural churches are drawing Black millennials and Gen Zers into movements that do not have a clear or full vision for social and political racial conciliation necessary to transform a continued racist society into greater diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

They are well dressed, and most are professional people. These members of a house church in suburban San José, Costa Rica, sang some choruses, then moved into Bible study, and concluded with a sharing of prayer needs. Afterwards, many stayed around to discuss the movie, The Late Great Planet Earth, over sandwiches and chocolate cake in one of the group’s periodic “film forums.”

They are well dressed, and most are professional people. These members of a house church in suburban San José, Costa Rica, sang some choruses, then moved into Bible study, and concluded with a sharing of prayer needs. Afterwards, many stayed around to discuss the movie, The Late Great Planet Earth, over sandwiches and chocolate cake in one of the group’s periodic “film forums.”The attenders look and talk like North American evangelicals, but the group leader explains something that might break that mold. While most come from conservative and Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship backgrounds, he explains, “it might come as a surprise to you that probably all of these people would vote for Marxist candidates in the Costa Rican elections.”

It is becoming increasingly difficult to put Latin American Christians into North American boxes. In fact, most Latin American Christians say one shouldn’t even try.

The frequently heard criticism of the church to the north is that Christians here too often judge and criticize without bothering to listen to their Latino brothers, while at the same time they are painfully ignorant of the Latin American culture and church.

Latin America Biblical Seminary professor Richard Foulkes explains, “Sometimes people from North America will just have to sit back and listen.”

Many Latin American Christians are asking how to live scriptural Christianity in difficult living situations—in countries that may have oppressive governments or thousands of poor with no chance of bettering themselves. The answers they are coming up with sometimes appear radical to those persons who, for instance, believe that the U.S. democratic and capitalist system is God-ordained, and that if it works in the U.S., it has to work in Latin America and anywhere else.

In El Salvador, an estimated 5 percent of the population own 80 percent of the land Even in Costa Rica, the most stable and affluent Central American republic, roughly 65 percent of the wage earners make less than 0 per month. In examining the options for improving such conditions, one prominent U.S. evangelical leader and long-time worker in Latin America commented, “It would be almost impossible for a U.S. missionary to work in Latin America and not become favorable toward socialism.”

Protestants in Latin America form a small minority—perhaps 25 million members. However, the church is growing: a recent survey showed that Protestant memberships in the Central American republics doubled or even tripled during the last decade. (PROCADES, a ministry of the Institute of In-depth Evangelization of Costa Rica, headed by LAM-USA associate Cliff Holland, is finishing an exhaustive study of Protestant membership in Central America. Through World Vision, PROCADES will publish English versions of its profiles of countries, which list Protestant churches, pastors, and organizations in the five Central American Republics, Panama, and Belize.)

There has been an explosion of new church bodies that are completely separate from North America mission ties. A recent survey showed 190 groups in Nicaragua, 41 of which list no U. S. or Canadian links.

At the same time, increasing tension is evident between U.S.-based missions and the churches their missionaries started. Many national churches want greater autonomy, and missionary agencies are not sure how they should (or if they should) relinquish control.

A small ad hoc committee, “Puente” (“Bridge”), composed of Latin American evangelical leaders and U.S. missions officials, functions to work through differences of this sort and to prevent conflicts of the kind that occurred in Costa Rica last January. Southern Baptists there went through a painful and messy split—some churches voting to sever all relationships with the U.S. church, and others choosing to maintain mission ties.

Generally, the grassroots Protestants in Latin America are theologically and politically conservative—explained partly in that 75 to 80 percent of Latin American Protestants are Pentecostal. (Latin Americans frequently use the term “evangelical” to describe any Protestant.) However, theologically conservative does not necessarily mean politically conservative, or vice versa.

Many pastors and churches strive to remain politically neutral, but are finding it increasingly difficult to do so because of pressures from the right and left (see p. 43). Others have felt conditions demanded their direct involvement. Believing violence the only way to halt the Somoza regime, allegedly responsible for widespread atrocities against Nicaraguans, some evangelical pastors there fought alongside the Sandinistas. Others, who did not fight, found themselves having to counsel teen-aged Christian young people who wanted to know if God would approve of them running to the mountains to join the Sandinistas. Most observers agree the revolution would not have succeeded without evangelicals’ support, and attribute the new Marxist-leaning government’s toleration, even support, of evangelical Christianity to that. At the same time, many evangelicals warn this toleration could cease when the Sandinistas no longer “need” the believers.

There are cases in which certain Latino Christians feel participation with Marxists or other non-Christian groups is the only way to present a strong enough force to fight a social or political evil. The house church members in San José, for instance, while knowing pure Marxists to be anti-God, may vote for a Marxist candidate if his election would mean improving conditions for the poor or stopping a corrupt right-winger.

In an address to a meeting of presidents of North American evangelical seminaries last January in San José, Dominican Republic educator J. Alfonso Lockward noted it is “almost impossible to avoid limited cooperation with Marxists in Latin America.” At the same time, he cautioned against evangelicals being “instrumentalized by Marxists without their knowledge.”

Lockward, a former presidential candidate in his own country, mentioned that attitudes toward political involvement among Latin American Christians range from the “ivory tower” approach (no involvement) to militant activity. He also complained that over the years, U.S. missionaries have exercised a double standard—forbidding their parishioners’ political involvement, while ardently supporting the political positions of the U.S. As an example, he cited a U.S. missionary to the Dominican Republic who became a decorated war hero in World War II, but who forbade his church members’ political action against the brutal Trujillo regime, which, Lockward asserted, committed atrocities just as awful as those by Hitler.

U.S.-based missionaries in Latin America also face difficult decisions regarding their own political involvements (or lack of them) and those of their Latino constituents. Earlier this year, at the Institute of the Spanish Language in San José—the chief language school for appointees of evangelical missions in the U.S.—missionaries encountered some of these issues. Two Mennonite college students attending the institute were ordered out of the country by the Costa Rican government; they had violated a little-used law forbidding foreigners’ political involvements by participating in a demonstration against Costa Rican and U.S. involvement in El Salvador.

Also, the murder in Colombia of Wycliffe missionary Chet Bitterman (a student at the institute just two years earlier), impressed the seriousness of the Latin situation upon many students—some of them headed for Colombia, and others, Wycliffe appointees.

The institute’s student government organized a round table discussion on the Christian’s approach to politics. While the consensus was that a missionary’s first task is presenting the gospel, several mentioned the impossibility of living isolated from one’s political context.

The missionaries realized that tough questions now facing some Latin American Christians are: When should a Christian seek to change corrupt systems, not only sinful man? Should expatriate missionaries support the cause of social justice?

Only 1 in 4 black Protestants identify with one of the eight historic denominations that compose the Conference of National Black Churches. Larger shares identify with evangelical or mainline denominations (30%) or offered a vague descriptor such as “just Baptist” or “just Pentecostal” (32%). The remainder said they were nondenominational (15%).

Among churchgoers, black Republicans are less likely than black Democrats to attend a black congregation (43% vs. 64%) and more likely to attend a white congregation (22% vs. 11%).

And while black “nones” are growing—now comprising almost 1 in 5 black adults (18%)—most of the unaffiliated still credit black churches with improving racial equality (66%) and more say that black churches have too little influence in society (35%) than too much influence (19%).

However, 6 in 10 of all black adults agree that “historically Black congregations should diversify” (61%). And those who worship at black (61%), white/other (66%), or multiracial (62%) congregations agree slightly more than those who seldom or never attend (60%).

“It is important to note that ‘multicultural’ generally means ‘monoculture with multicolors’ since most of the churches that fit this description tend to be white-led churches that have attracted blacks and not the other way around,” said Jeff Wright, the CEO of Urban Ministries.

The dominant culture’s “expectation” of “unilateral assimilation,” is something that Jacqueline Dyer, an associate professor of social work at Simmons University, has also noticed.

“I have had conversations with clergy who are noticing that in the wake of COVID-19, George Floyd and political unrest some Black church members in predominantly white churches are leaving to return to the Black Church,” she said. “The departing Black members are feeling disenfranchised.”

A continued one-way migration threatnes the gifts the black church offers not only to the black community, but to the Body of Christ as a whole, says Oneya Okuwobi, a researcher who studies the sociology of organizations, race, and religion.

“If we lose the spiritual heritage of the Black church as people and resources flow to other expressions, we will all be impoverished in the process,” said Okuwobi.

Meanwhile, 6 in 10 of all black adults agree that when church shopping, finding a new congregation where most attendees share their race would be “not too important” or “not at all important” (63%). A majority of those who worship at black congregations agree (58%), though they are less likely to do so than those who attend white/other (75%) or multiracial (69%) congregations or those who seldom or never attend (65%).

Liberation theology is at issue in school’s year of evaluation.President Carmelo Alvarez speaks almost proudly of 1981 as being “our year of evaluation.” At the invitation of the school’s board of directors, a seven-member team of theologians visited Latin America Biblical Seminary in San José, Costa Rica.This commission, selected to represent a broad spectrum of national and theological backgrounds, launched a full inspection in a week’s time. They talked with three former presidents of the school, with faculty who have recently resigned, students, and current school administrators. They are studying the school’s curriculum and facilities.Commission member Garth Rosell, academic dean of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, explained there is no accrediting agency in the Latin American world, such as the Association of Theological Schools. The seminary’s board of directors therefore “is very interested in input.”Yet Rosell would be the first to admit the reasons for the study (the seminary avoids the term “investigation”) go far deeper. The school’s alleged overemphasis on so-called liberation theology has earned it sharp verbal attacks since the middle 1970s. Some observers, even former president Plutarco Bonilla (1975–78), question its academic credibility, as well as its educational slant. The school hit a financial crunch when many conservative churches withdrew their support.When the commission releases its full report next month, the many nonbinding recommendations may appear uncomplimentary to the school. Commission head Cecilio Arrastía, a Hispanic programs official with the United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A., acknowledged “there are problems … theological problems.”Still, even many of the most severe critics assert their concern is to help the school, not hurt it. Established in 1923 by Latin America Mission founders Harry and Susan Strachan under the motto “For Christ and Latin America,” the interdenominational seminary (in Spanish, “Seminario Biblico Latinoamerica,” or SBL) for years held the reputation as providing the finest theological education for Latin American evangelicals. The school took the lead in providing pastoral training, which was taught by Latin Americans, and relevant to the Latin church and culture.But in its creditable efforts to relate theology to the troubled Latin American society, the seminary apparently upset a majority of its conservative, Protestant constituency. These grassroots evangelicals feel the seminary traded its historic emphasis on evangelism and building up the local church for a left-wing, political one.The seminary is small by North American standards—presently there are about 80 students in on-campus bachelor’s and licentiate (master’s) programs in theology, and another 100 or so in the “theological education at a distance” program. Yet its actual, and potential, influence is strong. Students come from practically all Latin American countries. The growing Latin American Protestant church needs trained leaders, and there are not all that many schools to choose from. If Latin America’s evangelical churches can’t send pastoral candidates to SBL, where can they send them?The Central American Mission’s seminary in Guatemala City is highly regarded, although some Latin theologians regard it as too conservative and dispensationalist. The U.S. Southern Baptists have seminaries in Cali, Colombia, and Buenos Aires, Argentina; the Evangelical Alliance Mission and the Evangelical Free Church of America jointly operate one in Maracay, Venezuela. If there is a criticism of these, it is that too few nationals serve on the respective faculties. The interdenominational ISEDET in Buenos Aires has top-flight academicians, but most Latin conservatives would feel uncomfortable there. One evangelical called it “the Union Seminary of Latin America.” Good Baptist, but Portuguese-language, seminaries in Brazil are also cited.But aside from these, many Latin evangelicals see only the separatist and conservative Bible institutes (many of these are tiny Pentecostal or fundamentalist schools) and liberal mainstream denominational schools. Theologian John Stam, who recently resigned from the SBL staff, sees a need for a good “third alternative,” somewhere between these conservative and liberal extremes. In his eyes, such a school would be “radical evangelical”—progressive in its approach to social issues, and evangelical in theology.Whether SBL will assume a leading role remains a question mark. Conservative evangelicals right now are skeptical. (Latin Americans frequently use the term “evangelical” to describe any Protestant.) But many do feel something can be learned by studying events there, which highlight key trends in the developing Latin American theology. A central question is: Can the Latin church address crucial social issues—such as poverty and political unrest—and at the same time be biblically sound and evangelistically active?Some missionaries and educators trace many of the school’s criticisms to North America evangelicals who do not really understand the Latin scene, and who air knee-jerk suspicions when something does not exactly fit their U.S.-formed concept of what a seminary should be and teach. Seminary officials frequently remind others that SBL is not a U.S.-owned or-operated school. It is owned and administered by an association of Latin American Christian leaders, and is responsible for its own financing and personnel.Because many North Americans think the Latin America Mission in the U.S.A. somehow controls the seminary, LAM-USA officials have spent a lot of their time denying responsibility for what goes on there. While LAM-USA missionaries may serve on the school’s faculty, the seminary functions independently of the U.S.-based mission.In 1971, the Latin America Mission was totally restructured and its many departments of ministry, including the seminary, became autonomous. Now, LAM-USA, LAM-Canada, and the seminary are among the some 25 separate entities that are members of the Community of Latin America Evangelical Ministries (CLAME).Independence from U.S.-based controls meant development of programs and ideals not always in line with those with which U.S. missioners feel comfortable. In the case of SBL, U.S. missioners became increasingly unhappy with the school’s drift toward liberation theology. The seminary rumbled through some troubled times in the middle 1970s, with ideological conflicts and numerous faculty changes.Developments to Watch in Today’s Latin ChurchSeveral trends characterize today’s church in Latin America, according to CLAME general secretary and CHRISTIANITY TODAY correspondent Paul Pretiz of San José, Costa Rica:• Continued growth of the charismatic movement, which has brought new vitality to the Roman Catholic church, and a crop of first-time Bible readers. Catholic charismatics often meet in house prayer groups, and, while many are rejected by the Catholic hierarchy, prefer keeping their Catholic identity rather than forming a Protestant one.• Sprouting of the small, grassroots worship communities, or base communities, among Catholics. There are 150,000 to 200,000 of these (an estimated 100,000 in Brazil) in Latin America. The groups have grown spontaneously, without a linking network, and generally are composed of the poor, who are reading the Bible and seeing its social implications.• Consolidation by the Catholic hierarchy, boosted by recent visits to Brazil and Mexico by the conservative Pope John Paul II. They are seeking to reaffirm traditional doctrine and bring offshoot groups “back into the fold.”• New ecumenicity among Protestants. Certain key Latin evangelicals are establishing a continent-wide fraternal body, CONELA (Consultation of Evangelicals in Latin America). They see their group as the conservatives’ alternative to the fledgling Latin American Council of Churches (CLAI) with its World Council of Churches ties. This group formed out of a meeting of 40 Latin Americans attending the 1980 Consultation on World Evangelization in Thailand. Executive secretary Marcelino Ortiz cited CONELA goals, including a transdenominational meeting in early 1982, an information network, and pastors’ retreats.• Development by local congregations of new worship models that are non-Western, and fitted to the Latin context. Experiments in evangelistic programs and theological education by extension also characterize many Protestant groups.Concerns refocused when LAM-USA decided 18 months ago no longer to endorse the seminary publicly. LAM-USA board initiated a year-long study in February 1979 to determine what should be the mission’s continuing relationship with SBL.In the report, issued a year later, LAM-USA noted its freedom to declare any of its theological or ideological differences of conviction or emphasis with the seminary. The mission also said it would continue sponsoring missionaries on the faculty. Finally, LAM-USA declared it “may also choose not to promote the SBL and to exercise its own criteria as it continues to engage in the communication of Latin American realities.”The mission communicated this report to certain key supporters and, as it has worked out in practice, said LAM-USA spokesman John Rasmussen, “we are no longer endorsing the seminary.” The mission no longer endorses the SBL in its publications, or raises funds for the school.Another recent development involves the Association of Costa Rican Bible Churches, which is composed mostly of congregations started by LAM missionaries. The association is starting its own Bible school in order to provide an alternative for the majority of the association’s 56 churches who do not support the seminary, said association administrator and LAM-USA missionary Bill Brown.Also, the resignation of Professor Stam shocked many observers, because Stam had identified so closely with the seminary’s push for a theological slant that more closely identified with the Latin American context.Stam, a professor at the school for 24 years, emphasized in an interview that his resignation was not meant as a statement against the seminary’s theological stance. Rather, he wanted to devote more time to grassroots pastoral work in Costa Rica and Nicaragua, as well as teach religion at the National University in Heredia, Costa Rica.However, he did admit his resignation was intended as an “alarm clock” for those who would allow the seminary to drift farther from its evangelical moorings.He also noted questions about lifestyle, such as standards now allowing students at the seminary to smoke, even though many conservative Latin churches would never accept a pastor who smoked and feel this would be the “kiss of death” to a student’s ministry. Stam’s resignation is one of at least five by faculty members who left during the past year for a variety of reasons.Richard Foulkes, who heads the seminary’s department of Bible and Christian thought, and his wife, Irene, Greek professor and director of the theological education “at a distance” program, are the last LAM-USA missionaries on contract with the seminary. LAM-USA associate Thomas Hanks teaches Old Testament there apart from his duties with a student ministry, but without a contract. He resigned from the faculty six years ago in disgust over a cutback in Bible courses, but stayed on, while working to strengthen and add to those that are offered. Mennonites Laverne and Harriett Rusch-man are the only other North Americans on a full-time staff of 14.Richard Foulkes and Hanks, while they agree certain evangelical doctrines have been neglected at SBL, presently intend to stay at the seminary and see it through its crisis period. They praise the school’s efforts to relate to crucial social issues in Latin America. They would not agree with all the views of certain liberation theologians on the faculty, but affirm the professors are evangelicals.One professor who left, Kenneth Mulholland, cautions North Americans against judging the school through their own filters. “This isn’t the old modernist controversy like we had in the U.S.,” he said.Mulholland, who left SBL last August for Columbia (South Carolina) Graduate School of Bible and Missions, believes all staff members affirm “classical, evangelical theology,” and would not quarrel with such key doctrines as the Virgin Birth. In fact, SBL in 1974 approved a conservative faith statement, “Affirmation of Faith and Commitment,” for its faculty. But what sets certain Latin scholars apart from others, Mulholland says, is their areas of emphasis.At the seminary right now, the main emphasis is social ethics, Mulholland believes. Problems come if an emphasis like this distorts biblical doctrines, such as the nature of man, he said.Liberation theologians with a Marxist slant “view man as inherently good, and corrupted by social structures, while Christians view man as fallen, and with evil proceeding from the inside out. Structures only magnify that evil,” he noted.He believes the seminary could “turn itself around” with renewed commitment to evangelism and the local church. “If those concerns came pressing in, with the school’s biblical evangelical heritage, it could regain the balance it has lost.”Questions about SBL always gravitate back to the so-called liberation theology, since this is the subject on which many believe it has gone off the deep end.Liberation theology works generally from identification with the poor, oppressed, and alleged victims of exploitative societies. Because the term means different things to different people, a better term is said to be “theologies of liberation.” Latin theologians often call it Latin American theology, calling it the first attempt since the early church to develop a systematic theology outside the European context.Evangelicals rebut those liberation theologians who view Christ as a political messiah, and who use Marxist thought as the starting point for their ideology. Most cite as redeeming factors its emphasis on faith practice, and its push to better the plight of the poor.Protestant treatments of liberation theology are found in: J. Andrew Kirk’s Liberation Theology: An Evangelical View from the Third World (John Knox, 1980); Orlando Costas’s The Church and Its Mission: A Shattering Critique from Ihe Third World (Tyndale, 1975); Carl E. Annerding’s Evangelicals and Liberation (Baker, 1977); Robert McAfee Brown’s Theology in a New Key: Responding to Liberation Theologies (Westminster Press, 1978); chapters from Tensions in Contemporary Theology, edited by Stanley Gundry and Alan F. Johnson (Moody Press. 1979); and the W. Dayton Roberts article in ct. Oct. 19. 1979. “Where Has Liberation Theology Gone Wrong?”Seminary professor Hanks, for instance, believes the emphasis on the poor is a key issue that North American evangelicals are ignoring. He says North Americans generally blame poverty on “underdevelopment,” or a person’s laziness or lack of education. However, he cites more than 120 biblical texts naming “oppression” as the cause of poverty. The church’s responsibility is locating those sources of oppression, and then denouncing them in the mode of the biblical prophets, he believes.The central complaint against SBL has been its alleged overemphasis on the left-wing political aspects of liberation theology, and a weak and flawed theological perspective on the subject.George Taylor, who left the seminary last December to accept a teaching post at Northern Baptist Theological Seminary near Chicago, says the seminary is right in teaching liberation theology. Such teaching is needed in the Third World because of its “identification with the poor,” he said. However, Taylor, a Panamanian who taught for 18 years at the seminary and was its interim president in 1974–75, adds that “maybe I was not in agreement with its heavy emphasis on politics.” He believes poverty must be addressed in the political arena, as well as the theological, but that the seminary now gives greater emphasis to the political aspect.Former seminary president Bonilla criticized the trends of the seminary more blatantly. Bonilla, a native of the Canary Islands who resigned last year from the faculty but is teaching a preaching course there without a contract, says the faculty and students are wrapped up in “political sloganism.” The theological course work has been diluted so much that the school lacks academic respectability, he asserts.Bonilla adds: “It seems to me that justification by faith is no longer one of the main themes at the seminary. I’m not saying the faculty don’t believe it, but they take for granted the theology and ignore it. The courses in theology are very weak.”Foulkes sees his continued role at the seminary as “keeping the biblical content high.” He laments the loss of Stam, a skilled New Testament theologian, but he is optimistic about the skills of new faculty members brought in to fill recent vacancies. He relies on Hanks to provide expertise in the Old Testament courses. Hanks complains of a “brain drain” of Latin American scholars; some of the most talented Latin theologians accept teaching posts in the States, such as Taylor, and Orlando Costas (whose resignation from the seminary in the middle 1970s over the liberal drift created tensions that some seminary sources say are still felt).Hanks and Foulkes both agree the seminary should attune students to the political realities of Latin America. Hanks did note problems can result if impressionable students get a one-sided view in the process. He describes a hypothetical SBL student as one who may be a new Christian and “may have read the Book of John and not much else.” The student may attend one class under an outspoken liberation theologian at SBL, and also classes at the University of Costa Rica (as many SBL students do) under a Marxist professor. With no counterbalancing explanations, before long the student “doesn’t know where he’s at,” Hanks notes.SBL president Alvarez, from Puerto Rico and the Disciples of Christ, says, “We want to help students understand what is going on in their own countries,” adding that the seminary can’t tell anyone what to believe.Alvarez, 33, a doctoral candidate in church history who has done graduate study in the U.S., criticizes North American Christians as “playing the church business and not taking seriously what it means to proclaim the kingdom.”People close to the seminary cite the election of a successor to Alvarez—whose three-year term expires in November—as crucial to the seminary’s future, and are hoping for a conservative evangelical. Former president Bonilla said he was asked to seek the post but turned it down because the seminary faculty “don’t show a willingness to change.”The seven-member commission’s report may provide direction to the seminary’s board. The team—not all members being conservative evangelicals by North American definition—has divided the work, each member focusing on a certain aspect of SBL. Besides Arrastia and Rosell, team members include Thomas Liggett, president of Christian Theological Seminary (Disciples of Christ) in Indianapolis; SBL alumni Julia Esquivel of Guatemala and Rodrigo Zapata of Ecuador (with HCJB in Quito); Aníbal Guzmán, a Bolivian Methodist; and Francis Ringer, of Lancaster (Pa.) Theological Seminary (United Church of Christ).When the team reports back to the SBL board with its full report in late June, commission head Arrastia hopes the results will be given a good hearing. The idea was that the report be used for SBL’s long-range planning through the next 10 to 15 years.Hanging in the balance, he says, is whether SBL “stays an evangelical seminary, or takes the full route of liberation theology.”GuatemalaGuatemalan Pastors: Between A Rock And A Hard PlaceThe Guatemalan pastors interviewed by CHRISTIANITY TODAY asked that their names be withheld for their personal safety.“We are trapped between right-wing and left-wing terrorists,” reported Guatemalan pastors recently. “Please ask Christians all over the world to pray for Guatemala, and for the believers here.”Violence has stained this emerald green Central American republic many times in its 160-year history. But rarely did the violence become as savage and sustained as it has during the current right-left battle for domination. Up to 25 violent deaths are reported daily in the national press, and many citizens believe the toll may be greater.Leaders of the Guatemalan evangelical church have tried to maintain a neutral position in the current political shooting match. But neither side seems content with the evangelicals’ neutrality.“First the leftist guerrillas come and want us to give them food and information, or they ask to use our church buildings for political meetings,” said one pastor. “If we refuse, they accuse us of supporting the right-wing terrorists. Then the rightists come and ask us for information or want us to preach against the leftists. If we don’t cooperate with them, they accuse us of defending the leftist guerrillas.”When a church leader does give in to the pressures, he is immediately marked by the other side for harassment, threatening letters and phone calls, or death. One informed source reported that three lay pastors were killed in Huehuetenango in late January. The same source also said that up to 10 local church leaders died violently during the first two months of 1981. Specific figures are hard to secure because some deaths have occurred in isolated indigenous areas, and local people are afraid to report the deaths because of possible reprisals.A climate of violent revenge has moved into some sections of the country and is a factor in many killings. An assassin will eliminate a client’s personal enemy for as little as . Some pastors have received anonymous threatening letters, presumably from disgruntled church members, which alarm them and their families.In other cases, right or left elements engage in “cleaning the record” operations. If any citizen has in the past belonged to or participated in political movements of either stripe, his adversaries may eliminate him for past actions, no matter what his current political attitude may be. Scores of Guatemalans have been shot in such “cleaning” operations. Church leaders who learn that their names are on a cleaning list will often leave the country hastily.Rightist officials are attempting to bring evangelicals into government programs to reunite Guatemala’s people. There is, however, the fear that joining such a program may create a leftist backlash against the evangelical church.Meanwhile, and in spite of the tension, churches are full. One pastor related, “We are seeing a harvest of conversions. The situation has awakened interest in the gospel, and people are coming to Christ.”“Christ is the only solution for Guatemala,” he went on. “As people repent of their hate and fear, and are reconciled by the Lord, they become new creatures.”Evangelist Luis Palau carried out a nationwide mass media crusade in Guatemala during April, using radio, television, newspapers, and thousands of specially prepared booklets.