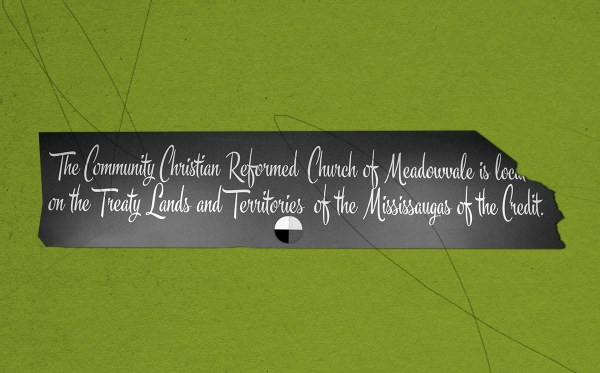

Visitors to a suburban Toronto congregation are greeted in the foyer or from the stage with the following: “The Community Christian Reformed Church of Meadowvale is located on the Treaty lands and traditional Territories of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation.”

The statement names the indigenous community that once stewarded the land where the Canadian church stands. But a visitor to one of Meadowvale’s hundreds of fellow American congregations across the border will likely find the practice of such “land acknowledgements” to be wholly unfamiliar.

The discrepancy is part of a larger divergence within the Christian Reformed Church in North America (CRCNA) as the denomination’s 1,000-plus congregations—with one quarter in Canada and three-quarters in the United States—seek to serve amid neighboring cultures and governments moving at very different paces on addressing injustices done to their indigenous peoples.

In Canada, where the native community is known as First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples, the abuse that many indigenous students suffered at residential schools was the subject of a national, years-long reckoning through a federally backed Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). In contrast, though many Native Americans in the United States experienced similar trauma, the schools’ aftermath has only recently gained mainstream attention.

“Because of the [TRC] and the things that the government has done, the Canadian church has been encouraged to continue doing the work,” said Viviana Cornejo, the CRCNA’s racial curriculum and instruction specialist. “The United States as a whole is having a hard time dealing with the past. If the country is not able to do that, the CRC is not going to do that either.”

The remains of Canada’s residential schools

In May, dozens of First Nations families had their worst fears confirmed. The remains of 215 students were discovered in unmarked graves on the grounds of a closed residential school in Kamloops, British Columbia. Weeks later, an estimated 600–751 unmarked graves were located at a former school in Marieval, Saskatchewan. And by the end of June, another 182 unmarked graves were found at a former school outside Cranbrook, British Columbia.

The findings provoked intense emotion. More than a dozen Canadian churches were destroyed or damaged by fires. Dozens more were vandalized. Though the attacks appeared connected to the revelation of the graves (given that the Canadian federal government had tapped Christian denominations to run the schools), many of the impacted congregations primarily serve immigrants.

Several cities canceled Canada Day celebrations planned for July 1. People placed teddy bears and shoes at memorials nationwide, creating visual representations of the lost children.

“In an era of reconciliation these precious 215 children should not be a brief emotional blip in the news cycle,” affirmed a statement signed by nine CRCNA leaders, including the denomination’s executive director. “Each one was a precious child and an image bearer of God. As the church—children of the reconciling Christ—tears of sorrow, prayer, and action are critical for the integrity of our reconciliation efforts.”

The statement came with nine suggested action steps, along with a prayer to be read by indigenous and nonindigenous Christians. (Almost two-thirds of Canada’s indigenous population identifies as Christian, according to the 2011 National Household Survey.)

The CRCNA never operated a residential school in Canada. However Roman Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian, and United churches did. Beginning in the 1980s, hundreds of residential school survivors began to file lawsuits against the Canadian government, ultimately becoming the country’s largest class-action lawsuit. The ensuing settlement agreement, approved in 2006, included payouts to survivors from the denominations and the federal government. Funds from these bodies also paid for the TRC, which ran from 2008 to 2015, allowing survivors to share their stories across the country.

The TRC initiative also culminated in 94 calls to action. The Canadian CRC congregations committed to several, including one that asked faith communities to affirm the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as a framework for reconciliation. The others called for equity in education for indigenous people and for churches to teach their communities about this history. On the ground, that means Canadian leaders have lobbied on behalf of educational justice issues and have also intentionally educated and resourced CRC congregations on the effects of colonization and residential schools.

“The results of the residential schools created the opportunity for settler acquisition of land and resources in this country,” said Mike Hogeterp, who leads the Centre for Public Dialogue, the denomination’s Canadian public policy arm. “Even though the CRC didn’t run a residential school, we are beneficiaries of the colonial system that the residential schools represented.”

This gesture was far from the denomination’s first touch point with First Nations communities. While the first CRC churches in Canada opened in the early 20th century, the denomination organized and matured in the years following World War II. When many First Nations people began moving off their reservations and into urban areas, the CRCNA starting in the 1980s opened ministry centers in Regina, Winnipeg, and Edmonton.

Some CRC congregations have initiated relationships on their own. The Toronto Blessing, a charismatic revival that began in 1994, spurred the Meadowvale church to learn the history of its land as part of a “spiritual-mapping exercise” of the city. Several years later, when Meadowvale organized a March for Jesus, the church invited members of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation after learning that the tribe had a significant Christian presence on its reserve. (In the early 1800s, Methodist circuit riders spread the gospel to the Mississaugas, a faith which endured.) Church leaders from both Reformed and Wesleyan communities began to pray with each other.

In 2000, Meadowvale organized a conference where members repented for past wrongs toward the Mississaugas. This gesture has deepened into two decades of friendship and partnership. Many church members attended TRC events and organized a community art project to highlight the commission’s findings. A Mississauga chief has now twice invited delegates at CRC events to acknowledge the tribe’s traditional territory. The church erected a sign with the land acknowledgement in 2017.

“By God’s grace, we were able to acknowledge the host peoples of the land before we were acknowledging the land itself,” said Sam Cooper, Meadowvale’s pastor. “For us, it was the relationship that was most important. A land acknowledgement can be a sign of a relationship, but we wanted the substance of that.”

While Meadowvale’s relationship has been somewhat unique among Canadian CRC churches, there is far greater awareness among Canadians of the hardship of indigenous people than when the church first began the work. A 2016 survey found that two-thirds of nonaboriginal Canadians had read or heard about residential schools, compared with only half in 2008.

The Evangelical Fellowship of Canada (EFC) has intentionally sought relationships with the indigenous community since 1994, when it and leaders from World Vision met with more than 30 First Nations and Métis Christians. The following year, the EFC formed an aboriginal task force to strengthen ties and to create relevant educational material for churches.

In the aftermath of the TRC, the EFC announced it was exploring “what it means for us as a broad evangelical community to embrace and enact the principles outlined in the UN Declaration as a framework for reconciliation” and committed to ongoing learning and reconciliation. In 2020, a committee of indigenous and nonindigenous Canadian evangelicals recommended seven specific reconciliation goals, which the EFC accepted.

“It is challenging, often difficult to fathom, especially as a Christian trying to come to terms with what was done in the name of the Christian faith and rationalized within the public square,” wrote EFC president Bruce J. Clemenger in the aftermath of the grave findings. “To come alongside Indigenous sisters and brothers is to listen and ask questions. When we own the shame of what was done in this land to our neighbours and their ancestors, we will be motivated to pray and seek healing for our country.”

In the wake of the TRC, Canadian schools—including private ones—now teach about the history of residential schools. Andrew Beunk, who pastors New Westminster Christian Reformed Church in Burnaby, British Columbia, says his wife serves as a vice principal at a CRC school and that the curriculum additions have been well received.

Though he attended a TRC session and was moved by the stories of survivors, he has felt less comfortable introducing land acknowledgements as part of his church service.

“Since we have no people in the congregation who are part of the indigenous community, we felt in some way that was a bit inauthentic,” said Beunk of the discussion. “Since we don’t have meaningful connections, to just jump on board it felt a little bit disingenuous.”

He also has theological apprehensions.

“As Christians, all the land belongs to God,” he said. “To accent historical and in some cases political differences in a worship service—I have some issue about doing that.”

America’s lack of acknowledgement

Whereas few indigenous leaders hold CRC leadership positions in Canada, Navajo and Zuni pastors can be found in the American Southwest. The denomination’s first missionaries to Native Americans arrived in Arizona in 1896 before pivoting to Gallup, New Mexico, where local CRC congregations today are concentrated. Part of their ministry involved opening a residential school, with a history that often mirrored its Canadian contemporaries.

As Rehoboth Christian School’s website explains:

Although many families were introduced to the Gospel through Rehoboth in its early boarding school days, there were components of the methodology used to present Christ that Rehoboth now laments. Becoming a Christ follower sometimes appeared to be confused with becoming more like a white American. Many aspects of Navajo culture were prohibited, including the speaking of the Navajo language. The boarding school experience for some children resulted in trauma as they lived away from that which was familiar, especially their families.

Still in operation, Rehoboth exists today as a day school. During its centennial in 2003, leaders of the school and of Christian Reformed Home Missions repented for disrespecting the culture and people the institutions had sought to reach. In turn, the head of the Red Mesa classis, the CRC term for a group of neighboring churches, asked forgiveness for his indigenous community’s bitterness toward their Anglo brethren.

In 2012, the CRCNA launched a task force to research the effects of the Doctrine of Discovery on indigenous people in the US and Canada. In 2016, the denomination rejected as heresy this theological framework, which had allowed European Christians to justify taking and ruling over land that was already inhabited by indigenous people. (The Evangelical Covenant Church issued a similar repudiation last month.)

The CRCNA also stated that it recognized “the gospel motivation in response to the Great Commission, as well as the love and grace extended over many years by missionaries sent out by the CRCNA to the Indigenous peoples of Canada and the United States. For this we give God thanks, and honor their dedication.”

The two declarations showcased a tension among US-based CRC congregations. Two New Mexico–based churches serving indigenous communities criticized the task force’s report for selecting “some of the ugliest moments of that past in order to make their accusations against these early missionaries stick.” But others felt that the desire to protect the missionaries came at the expense of telling the stories of those who had suffered as a result of the denomination’s initiatives.

“For my work with the Navajo, the CRC has still not done the right work yet,” said Cornejo, who is based in Michigan. “They need to recognize what they did, recognize how they started, and that they followed the pattern of all the other boarding schools.”

Cornejo’s team has educated various American congregations, often by teaching the Blanket Project, an interactive storytelling tool used on both sides of the border to viscerally illustrate the indigenous experience. After 2016, her team heard from many churches eager to bring it to their communities.

But broad awareness remains a challenge. Far fewer Americans know the full extent of their country’s past and present treatment of Native Americans, and unlike in Canada, land acknowledgements have yet to be normalized. An official apology to Native Americans in 2009 introduced by then Kansas senator Sam Brownback was buried in a defense appropriations bill. (This month, Brownback and Yuchi pastor Negiel Bigpond launched an effort to revive the apology.)

The lack of American awareness could change. In the aftermath of the discovery of the Kamloops graves, US Interior Secretary Deb Haaland announced an investigation into past oversight of Native American boarding schools in order to “uncover the truth about the loss of human life and the lasting consequences” of the institutions, which across the decades forced hundreds of thousands of children from their families and communities.

The resulting report may provide nonindigenous CRC churches the opportunity to engage their congregations around indigenous issues.

“Land acknowledgements are starting points for conversations,” said Shannon Perez, who comes from the Sayisi Dene community and serves as the justice and reconciliation mobilizer for the CRCNA’s Canadian Indigenous Ministry Committee. “Why is it important to understand the land you’re on? The Doctrine of Discovery has engrained on us that indigenous people weren’t on this land before and this land is for the taking. It was free for development without regard for the people that made their life there.

“In doing a land acknowledgement,” she said, “it changes, it disrupts, it challenges that narrative.”

Yet Jose Rayas doesn’t feel like a land acknowledgement would make sense at the Hispanic congregation he leads in El Paso at the Texas border with Mexico.

“It would almost seem like they’re blaming themselves,” said the CRC pastor. “A lot of the mindset that comes out here around the border is ‘Are we really responsible for something that we didn’t do?’

“If you’re talking to people of Hispanic descent,” said Rayas, “they are going to be questioning, ‘What responsibility do I have for something from 500 years ago? I’m still on the land that was taken from my people where my people are living. It doesn’t make sense.’”

Overall, churches who currently don’t have any personal relationships with indigenous peoples shouldn’t be wary of incorporating land acknowledgements, says Carol Bremer-Bennett, who is of Navajo descent and leads World Renew, the CRCNA international relief and development agency.

“Word may get to indigenous people in the area who will hear this is a space that is welcoming,” she said. “They may have visited the church or wanted to connect to it but didn’t see themselves as being an important part or included in the community. You never know where that could go.”

Bremer-Bennett says a land acknowledgement, when “done properly,” recognizes that indigenous peoples remain. “Too often, we’re treated as if we were a people of the past and we no longer … have a significant role in what’s going on today,” she said. “It makes me feel seen.”

The last several months have been hard for many Canadians. In the wake of the discovery of the unmarked graves at former residential schools, dozens of churches have been vandalized or burned to the ground. “These churches represent places of worship for community members as well as gathering spaces for many for various celebrations and times of loss,” the Lower Similkameen Indian Band said in a statement. “It will be felt deeply for those that sought comfort and solace in the Church.”

And yet, Perez considers that even when indigenous people were confronted by news of the graves, their primary response to the injustice was to invite the nonindigenous to grieve alongside them. (As the national chief of the Assembly of First Nations told Canadian media, “To burn things down is not our way. Our way is to build relationships and come together.”)

“In the midst of what could be righteous anger and demand for the extreme because of this injustice, that wasn’t the direction indigenous people took,” said Perez. “From that, we can say that the question of land and restitution is a conversation, but it doesn’t have to be one done in fear. Where do we put our faith? Do we put our faith in the land of wealth, or in the land of God?”