Nestled in the Ozark Mountains of Missouri, Evangel University will no longer evoke the Middle East—or the Middle Ages.

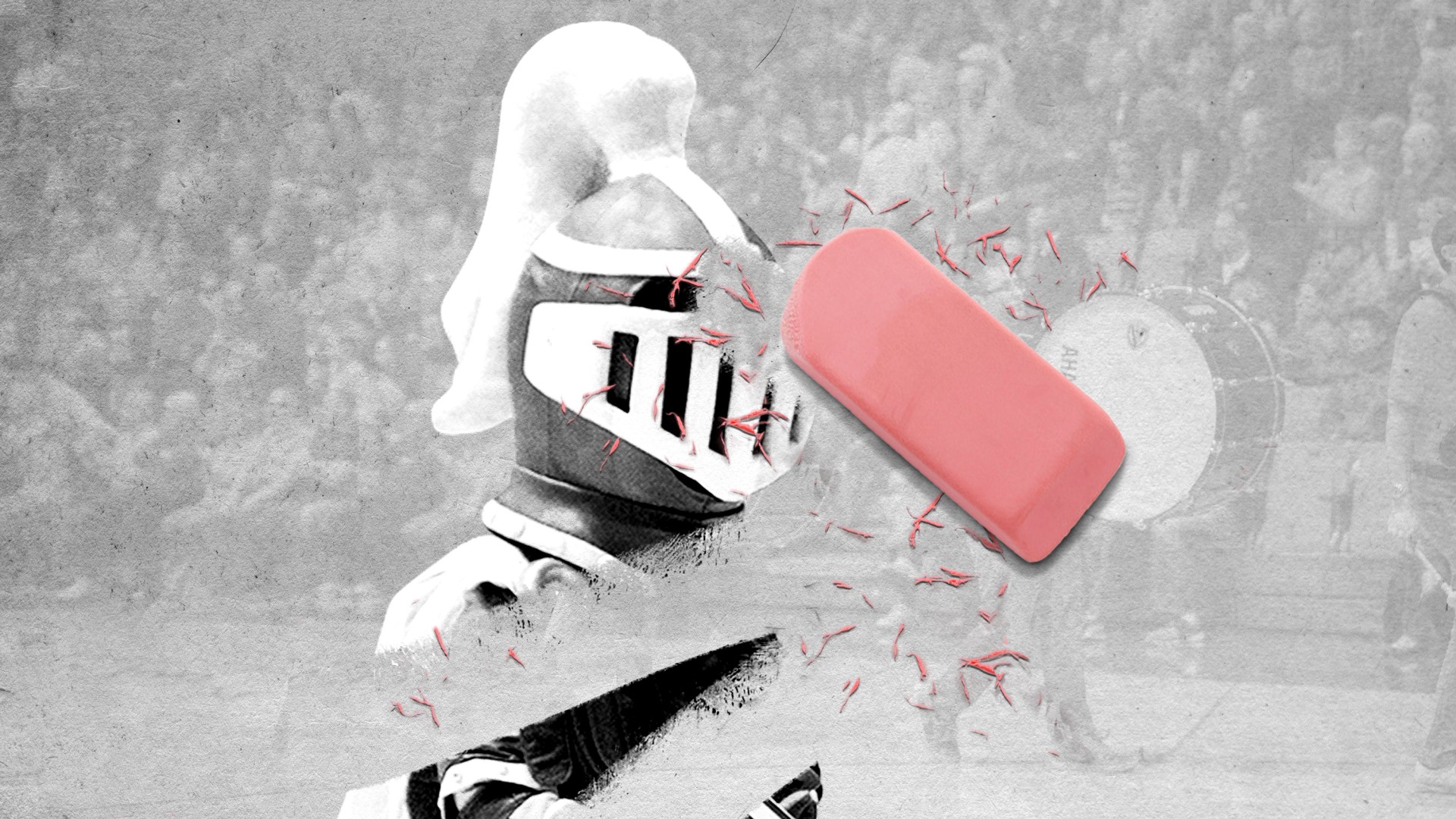

Since 1955, the flagship Assemblies of God institution has cheered on its Crusaders, replete with helmeted knight and steed. Now the knight is gone, and Evangel will root for Valor, represented by a horse.

“The evolution from a Crusader riding a horse to the horse itself was an intentional shift,” the university announced September 22. “The horse is a vehicle used to share a message, just as God inspires Evangel students to share the good news of Christ.”

The university considered almost 300 submitted suggestions—including 77 animal names, 69 military names, and 38 biblical names. The change was made in light of the school’s 55,000 alumni serving internationally.

“The world has changed significantly since the 1950s, when the Evangel community, intending to depict strength, honor, and commitment to the faith, first identified a Crusader as the school’s mascot,” stated interim president George O. Wood in March, when the decision was made to drop the name.

“Today, we recognize that the Crusader often inhibits the ability of students and alumni to proudly represent the university in their areas of global work and ministry.”

For some alumni, the change is a long time coming. The review process first began in 2007.

“When you want to share the love of Christ, you don’t want to identify with something that shuts down conversation,” said Emily Greene, class of 2008. “It is the equivalent of saying ‘jihadist’ to a US Christian, evoking a cruel persona.”

Greene grew up as a history-loving missionary kid in Muslim-majority Kazakhstan. But her father sat her down when she first encountered the Crusades, and told her plainly: We don’t use that word here.

As she studied more deeply, Greene discovered that the Crusaders were not necessarily the good guys. But at Evangel, the imagery was everywhere. The campus newspaper was called The Lance. The cafeteria was “The Joust.”

In her senior year, Greene signed a petition against the Crusader name.

But the distaste came not only from her unique upbringing. Her American, non-Christian family members have also chafed at the university mascot.

Not as severely as many Muslims, of course.

“One thing about history here, they never forget,” said an American Christian worker with ties to Evangel, who requested anonymity for the sake of his ministry in Turkey.

“Many believe missionaries are the modern Crusaders.”

He described posters urging parents take caution against such foreigners throwing their babies off a cliff. Common is the sentiment that Christian workers are also spies.

“I believe Evangel is doing the right thing,” he said. “We are extremely careful to not bring up that [Crusaders] name in any sort of context.”

One month before Evangel, Valparaiso University, a Lutheran institution in Indiana, announced in February it was dropping its own Crusaders nickname. Last month, the school rechristened its sports teams the Beacons.

“We are beacons of knowledge for our students’ academic, social and spiritual growth,” said university president José Padilla, connecting the new name with a school motto: In Thy Light, We See Light.

“Above all, we are beacons of God’s light around the world. We light the way for our students, so that once they graduate, they shine their light for others.”

But contrary to Evangel, the school popularly known as “Valpo” enrolls a sizable Muslim community. While centering its Lutheran heritage and mandating the study of theology, the school does not require a statement of Christian faith for students.

“As a Muslim, I was embarrassed to come to Valpo because the school’s mascot was a Crusader, even though my mom and older siblings went here before me,” said Jenna Rifai, class of 2021.

“It’s like, in their minds do they accept me? Are they anti-Muslim? I know it seems like a small little image, but symbols hold power.”

But Rifai also became well known on campus for her TEDx talk at Valparaiso, where she described how winsome interactions with students during a feared class on “Trump’s America” helped her find peace.

The class was taught by Heath Carter, now associate professor of American Christianity at Princeton Theological Seminary.

“There has been a lot more scrutiny of names and mascots in recent years, and it represents a critical turn in how we view our history,” he said.

“As a Christian, I think it can be very faithful to reassess what we lift up as our examples and models. There is a reckoning happening, and it is possible to see Valpo as part of this movement.”

Evangel, however, was quick to distance itself from any wider societal movements. Its FAQ page emphasizes the mascot change is not a “cancel culture reaction,” but one required by the school’s “Christ-centered focus.”

It is somewhat of a trend among Christian institutions, however. Wheaton College dropped its Crusaders nickname in 2000, followed by the University of the Incarnate Word in 2004, Northwest Christian (now Bushnell) University in 2008, Eastern Nazarene College in 2009, and Alvernia University and Northwest Nazarene University in 2017.

But according to mascotdb.com, which lists hundreds of high schools and higher ed institutions that have held the moniker, about a dozen colleges still use it, including the College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts.

“The literal definition of the word, ‘one who is marked by the cross of Christ,’ was appropriate for our institution’s Jesuit and Catholic intellectual and spiritual tradition,” stated president Philip Boroughs in 2018, when the college decided to keep the name.

“We are crusaders for human rights, social justice, and care for the environment; for respect for different perspectives, cultures, traditions, and identities; and for service in the world, especially to the underserved and vulnerable.”

But the image still caused consternation. One month later, Holy Cross dropped its knight as the university mascot, to be phased out entirely from the school’s symbolism and branding.

Will it make a difference?

From across the ocean, Middle East evangelicals demur. Whether the anti-Crusader spirit is a consequence of US domestic politics or concern for the gospel around the world, their issues are far greater than fluffy mascots.

“Americans are sensitive and try to accommodate everything and everyone,” said Wageeh Mikhail, the Egyptian engagement director for ScholarLeaders. “But I don’t think it makes any sense to Muslims or Christians in the Middle East.

“It is irrelevant.”

Instead, he focuses on the modern mistranslation of Crusades into Arabic. An expert in historical Muslim-Christian relations, he said that contemporaneous Muslims, Christians, and Jews all referred to the Middle Ages conflict as “the Wars of the Franks.”

It was not until about the 18th century, Mikhail said, that Muslim polemicists began translating the conflict as “the Wars of the Cross-bearers.” But today, this is the term that has universal usage in Arabic.

Imad Shehadeh, president of Jordan Evangelical Theological Seminary, made a similar point, emphasizing that most Middle Eastern Christians stood with the Muslims against the Crusaders.

But given the misuse of a perfectly good word—crusade—he resonated with the College of the Holy Cross.

“It would be better to give the true intention of the word rather than fall for the unfair and damaging way it has been portrayed,” he said. “We cannot keep changing our vocabulary just because some group uses it, not literally, but with a nuance intended to harm.”

Martin Accad, however, resonated with Jenna Rifai. Symbols do hold power.

“Christian students can sit in their dorm at Valparaiso and read about the fact that Jesus taught us to love and to be peacemakers all they want,” said the associate professor of Islamic studies at Arab Baptist Theological Seminary, in Beirut.

“But then they go out to watch a football game and to cheer for the team, and the Crusader mascot has more impact on their subconscious than all the books they’ve just read.”

Meanwhile, Muslims have their own issues, he said.

Mosque preachers are also adept at stirring up a crowd. Even when their complaint is political, theologically tinged rhetoric often predominates.

Accad highlighted the term kafir as especially problematic. Translated as “unbeliever” or “infidel,” moderate Muslim scholars often fail to admit the real harm such classical language causes for contemporary interfaith relations.

“Christians and Muslims both have a lot of work to do in terms of revising elements of their religious language that poison everyday relations,” Accad said.

“We have to create new symbols.”

Hussein Shahine, a Shiite Muslim, thinks Beacons works just fine.

“It will help Valpo’s identity of the school rest on something stronger: its academic reputation,” said the 2017–18 student body president. “Crusaders didn’t offend me, but I understand how the history might make people uncomfortable.”

It does for him—but with a twist.

Born in Dearborn, Michigan, Shahine spent time growing up in one of the Christian villages of the Shiite-majority Baalbek region in Lebanon. He heard church bells every Sunday and never considered that his religion made him different from other Lebanese.

Until studying the Crusades.

“Sunni Muslims destroyed the Shiite caliphate of Egypt, and the Syrian mujahideen treated us like scum,” he said of Saladin’s 1169 occupation, before the sultan launched his campaign against the Crusaders.

“There were massacres on all sides, and nothing good came of it.”

His older brother applied to Valparaiso on a football scholarship, and their father chuckled when learning of the then-mascot. But as student body president, Shahine never heard Muslims complain.

And years later, his family is still proud of their association with the school.

“Valpo really is a place of light, and made us good men of character,” Shahine said. “I am proud to call myself a Crusader.”

It is a fitting tribute to Christian education. But names still matter—deeply.

“Evangel was a very good school, and it shaped me,” said Greene.

“But I would never call myself a Crusader.”

Editor’s note: This article was updated September 22 to include the selection of Valor as Evangel’s new mascot.