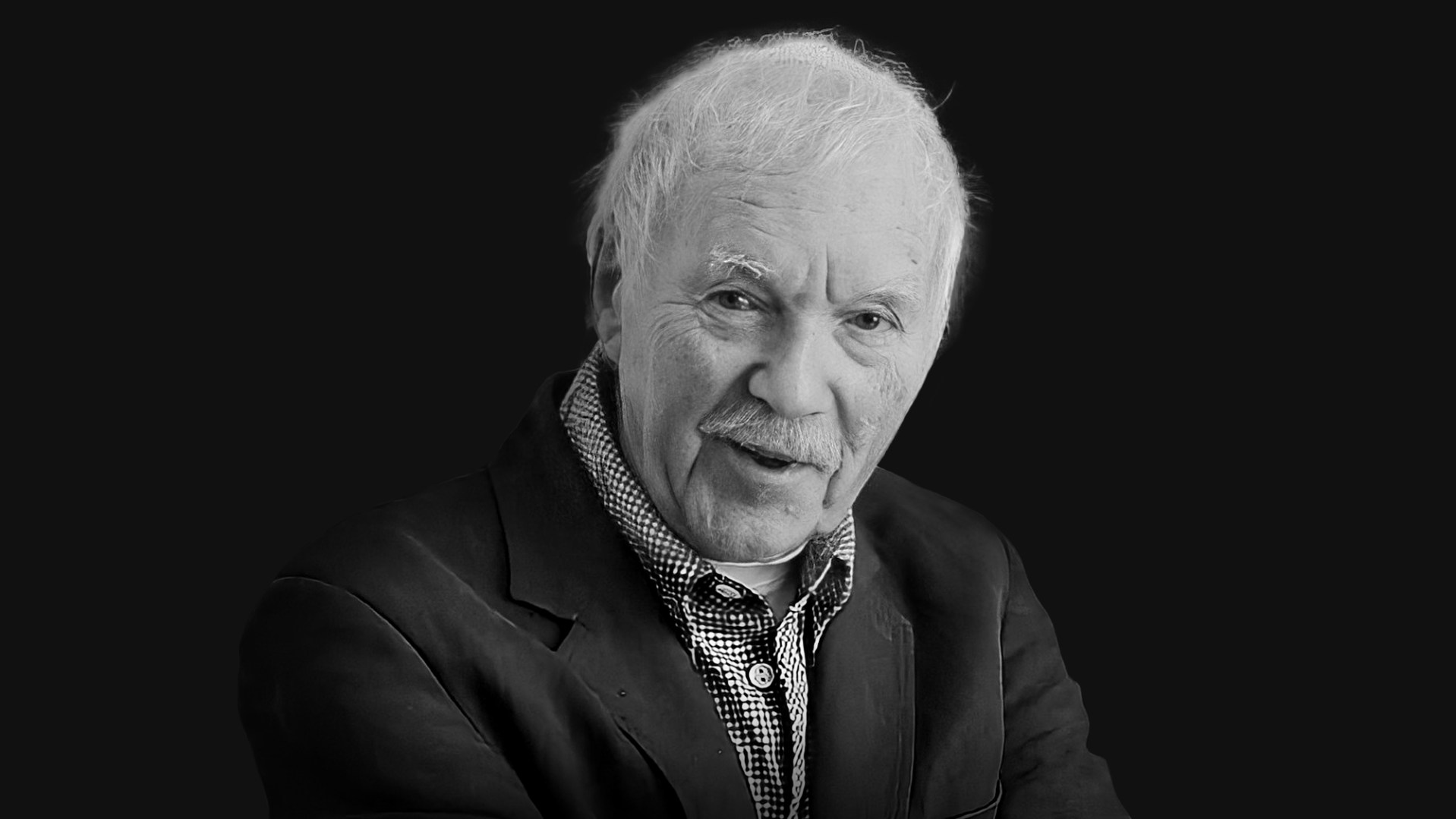

Kees de Kort, an artist who gave generations of Dutch and German children their first indelible impressions of Bible stories, has died at home in the Netherlands. He was 87.

De Kort sold more than 33 million children’s Bibles worldwide and became so popular in the Netherlands and Germany that “De Kort” is sometimes understood as a synonym for “children’s Bible.” For many modern Europeans, “the biblical cosmos of images is unthinkable” without his work, according to the German national newspaper Die Zeit.

De Kort’s depictions of Bible stories were bold and simple enough to capture the imagination. His figures solid enough to seem real and relatable. As De Kort himself once explained, he wanted to paint a Christ who could ride a bike—who could live and move plausibly in the same modern world that Dutch children knew from their everyday lives.

Journalist Lodewijk Dros said that as those children grew up, they found that “Kees de Kort’s children’s Bible is one of a few that stays with you.”

As news of De Kort’s death on August 19 circulated on social media, fans shared their favorite images online. A number recalled one in particular: a portrait of Bartimaeus, the blind man who receives sight on the road to Jericho in Mark 10:46–52.

“I still see that image before me: that man shouting with his mouth wide open,” said Hanna van Dorssen, a theologian with the Protestant Church in the Netherlands. “So evocative.”

Lisbeth van Es, curator at the Icon Museum in Kampen, said the portrait has all the essential elements of De Kort’s style.

“Simple colors and not too many details. You can see at a glance what the essence of what he wants to express is. … That is truly an iconic image,” she said. “You hear from everyone who grew up with De Kort’s drawings: They always stay with you.”

De Kort was born December 2, 1934, in Nijkerk, about 60 kilometers east of Amsterdam. His parents were devout Catholics, but it was a Protestant area. As an adult, he felt comfortable in Catholic and Protestant spaces.

“I’m a practicing Christian,” he said in 2020. “I pray twice a day, morning and evening. But I’m not fundamentalist. I go to Calvinist, Reformed, and Lutheran churches just the same as Catholic ones.”

He began his career at 27 in the secular world of technical drafting. But by 30, he found he was bored by the work and dreaming of something more. A colleague pointed him to a competition organized by the Dutch-Flemish Bible Society for a proposed series of picture books for children with intellectual disabilities.

De Kort waited until the last possible minute and then submitted a single painting: Mary and Joseph arriving in Bethlehem. The judges for the contest—Protestant pastors, Catholic priests, and Jewish rabbis, as well as children’s psychiatrists and psychologists—chose him.

When he won the commission, De Kort set out to establish a distinct style for his Bible illustrations. He studied children’s art and asked his two sons, aged four and seven, to explain their paintings to him. Children, he noticed, composed images on a clear horizontal line, with human figures at the center, generally seen slightly from below. They used bright colors and simple shapes but added more detail to emphasize emotions. He adopted all those elements into his own work.

Some observers connected De Kort’s illustrations to a movement within modern art that valued older, simpler forms, such as Pablo Picasso’s “primitivism” or HAP Grieshaber’s resurrection of woodcuts. His work was most frequently compared to Marc Chagall’s fairy tale-like Jewish art.

De Kort thought those comparisons were overblown. “Chagall?” he asked Die Zeit. “Another universe.”

His work, he said, was inspired by the Bible. He loved the stories.

“All kinds of things take place in the Bible, events that we also experience today: war, hunger, disease, corruption, oppression, slavery,” he said. “They are stories of friendship, comfort, and that nothing can separate us from the love of God.”

The first volume of What the Bible Tells Us was published in 1967. It was a small book, about five inches by five inches. Over the subsequent decades, De Kort produced 27 more, with the Bible society selecting the stories but giving him artistic freedom to illustrate how he chose.

One volume won an award for best schoolbook at an international book fair in Leipzig in 1977. Another won children’s book of the year in 1988.

The simple text, authored anonymously by Bible society staff, was translated into 90 languages. All 28 volumes of What the Bible Tells Us were combined into a single 348-page volume in Dutch in 1992. A German version, titled It Began in Paradise, was published in 1995.

De Kort was also commissioned to produce art for churches. He did a series of 10 pieces that were turned into stained glass windows in Mühltal, Germany; another for a church in Assen, Netherlands; and a series of 10 drawings for the Vatican in 2017.

His art has been displayed in more than a dozen art galleries and museums, frequently drawing critical acclaim. In 2019, the Icon Museum in Klampen paired his art with historic Catholic and Eastern Orthodox icons, making the case that De Kort’s work was iconic not just in the sense of being memorable, but also in the sense that it connects viewers to a spiritual reality.

“An icon is the real representation of the sacred,” said Van Es. “His works carry the essence of the Bible stories with them. … I consider his work a Bible translation. In a lot of religious art, there is an interpretation, an explanation, an illustration. Steps have been taken between the biblical story and the art itself. Not for De Kort.”

De Kort, for his part, said he learned a lot about visual narrative from Catholic icons, but he also saw his figures as more earthy and grounded—“tough Protestants.”

Toward the end of his life, De Kort took on another earthy art project and started painting pigs. He said he’d been thinking about how to depict them since he illustrated the story of the Prodigal Son in the 1970s. Also, they reminded him of his childhood.

“We lived next to farmers who kept lots of pigs,” he said. “They have always fascinated me. Pigs are wonderful animals.”

The Bijbels Museum in Amsterdam is planning an exhibit of De Kort’s work in December.