Sami DiPasquale runs Abara , a ministry that works on both sides of the border in El Paso, Texas, and Juárez, Mexico. The ministry has served the surge of asylum seekers, a fraction of whom are now being bused and flown to New York; Washington, DC; Chicago; and Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts. Some migrants are glad for the free ticket ; others allege they were deceived about their destination. About 11,000 migrants have arrived in New York City since May, with the mayor saying that the city’s shelter system is reaching a “breaking point.” But for ministries at the border, this is business as usual.

Thousands of migrants cross the southwestern border each day, and the surge in crossings has led to a record number of arrests this year. About half of migrants arriving are allowed to stay in the United States and pursue asylum claims. The surges in crossings go up and down. Most of those seeking asylum now are Venezuelans, among the millions fleeing a socialist regime. Christian immigration experts and lawmakers from both parties have said that the border shows a need for more judicial resources to process migrants’ cases.

How should Christians think about the thousands of migrants at the border?

Through media and social media, it gets painted like most people are at one crazy extreme or another on immigration, when I think most people are trying to grapple with what they feel is ethically right and compassionate.

What’s our posture? It’s easy for us in the US, at least for those that have been in a stable environment for a few generations, to be thinking about it as “How does God tell us what we do for people that are arriving?” But in so much of the Bible, especially the Old Testament … The Israelites, they were the people on the move. It wasn’t just about receiving people. All of us have our own migration journeys—God with us on the move and then God with us in stability.

What are your staff and ministry partners in Mexico seeing?

They’ve been very busy ever since “Remain in Mexico” [the Trump administration policy that required asylum seekers to await the outcome of their cases in Mexico] went into effect, and then we layered it with Title 42 [a Trump and Biden administration policy to turn migrants away at the border based on COVID-19 being a public health emergency].

Basically, there’s various layers blocking people from accessing the US border. That did not decrease people leaving Central America—it stopped us seeing that crisis on US soil. It piled up on the southern side of the border into Juárez and other Mexican cities to the north.

It’s very dangerous for migrants there. For me to go across as a US citizen, there’s hardly any danger at all. I am not the target. Those who are most vulnerable are those who have the least resources, who have maybe made a terrible trek and are then getting extorted even more.

Three or four years ago, migrants were almost exclusively those from Central America, and then more came from other parts of Mexico, fleeing similar root causes, a lot of it gang violence. And then we saw more from Haiti, and now more and more from Venezuela.

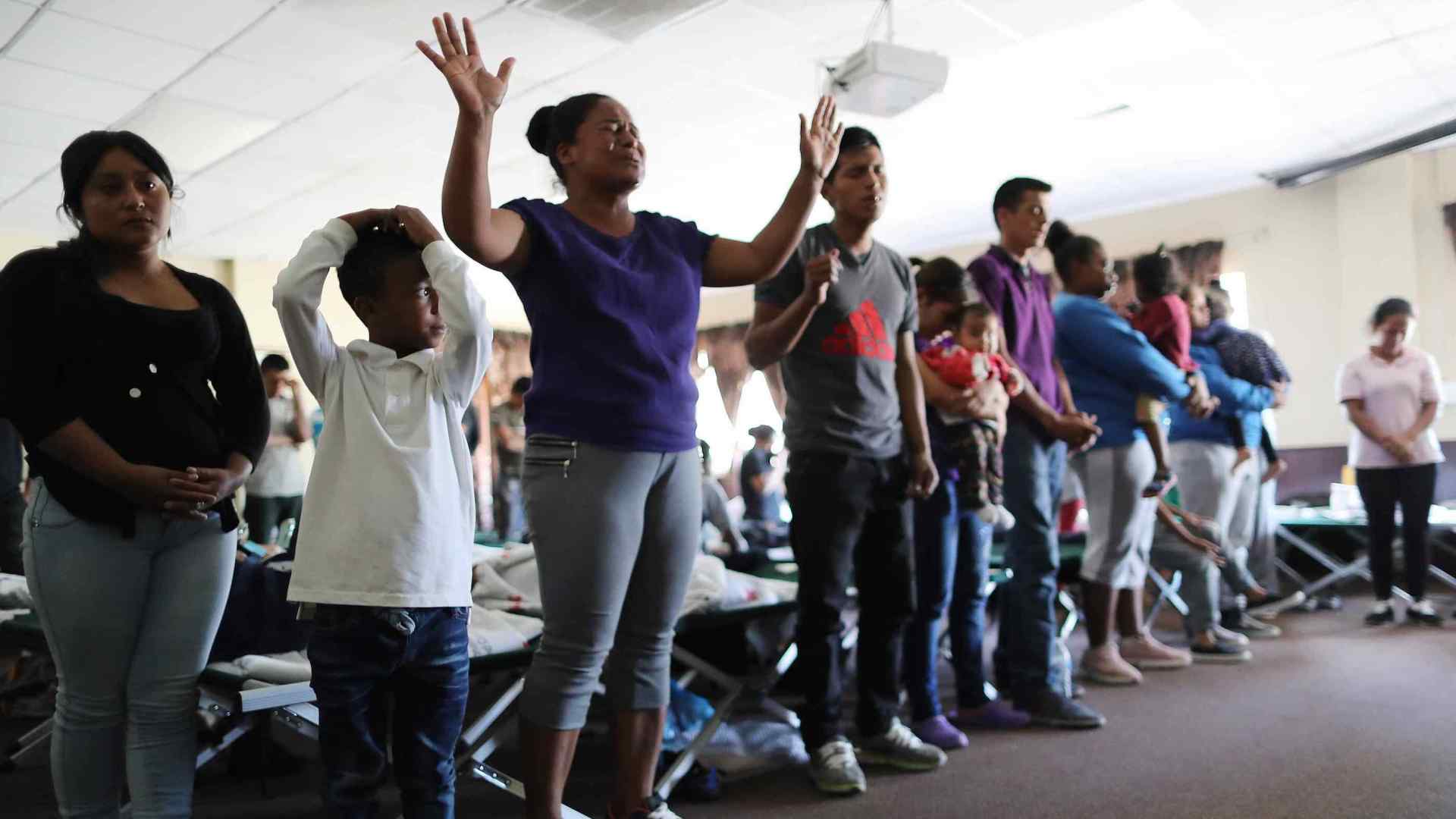

These shelters in Mexico, almost all of them are evangelical churches that have opened their doors. And it wasn’t because they have this in their mission statement or they have all this extra space. It’s because they saw the need and they felt like this is what Jesus would want them to do. It’s a great sacrifice. People have come in and often stayed in a church sanctuary for months.

What do migrants arriving in the US think about these buses to other cities?

In other parts of Texas, some of the people were put on buses to destinations where they had no interest in going. It seems that there’s motivations other than helping people get to a sponsor family.

But the city of El Paso has been chartering some buses, and at least the stated intention is to facilitate distributing people from temporary shelter at the border to places that are closer to where they want to end up with their sponsor family.

Most people have a sponsor family that they can live with, whether they’re in New York, Chicago, Memphis—every state, practically. They have a destination and someone who’s agreed to host them while they go through the asylum process. That’s not the case necessarily with Venezuelans now. That’s becoming a challenge.

Why do Venezuelans need support in particular?

Most people don’t realize that you’re not allowed to legally work in the US while you’re pursuing your asylum case, at least for six months. So how are you supposed to support yourself? That’s where the sponsor family comes in. But then, if someone doesn’t have a sponsor family—which a lot of Venezuelans don’t—then what are they supposed to do?

Then you might ask, “If we have low unemployment and we have all these jobs that need to be filled, why not make it legal to have temporary work visas?” And I think that’s a very good question.

New York, where I live, is prepared for immigrants coming to the city, but maybe not for thousands showing up at once like happens daily in El Paso. What can churches around the country do if migrants arrive in their communities?

A lot of people that are arriving, probably all they need is one or two days of help. US churches can provide hospitality for up to 48 hours, sometimes even less—a shower or a change of clothes and then food. And then somewhere to sleep overnight. That’s pretty much the time that it takes for someone to get in contact with their sponsor family and get a ticket, whether a bus ticket or a flight for where they need to go. Typically the burden of the transportation is on the sponsor family.

Here, one church within the El Paso Baptist Association had space but not enough volunteers and resources to open their space locally as a hospitality center. Then the whole El Paso Baptist Association for the city [78 churches] took on recruiting volunteers and having a point person and providing donated items, like a travel bag or toiletries. So you have a whole network surrounding this one physical hospitality center.

What’s it been like in El Paso?

The last month was critical because there were too many people within the Border Patrol detention facilities. They were warning, “We’re going to have to release people onto the streets if there’s not enough shelter capacity.” A bunch of people opened up shelters, but there were still releases on the street. Now it’s not happening anymore. Whether it happens again in the future, I’m not sure. At Abara’s guesthouse, we hosted groups of about 15 at three different points.

You have the contacts to get texts about migrants needing shelter. How do churches in the rest of the country get in that phone tree?

Any of the groups involved in refugee resettlement are also working with asylum seekers who are arriving. So wherever a church is, if there’s a World Relief, a Catholic Charities, a Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, or Jewish Family Services, look for them.

If churches were interested in helping relieve, for instance, the pressure in El Paso and offer another site, then they could get in touch with Abara. There’s also more openness to creativity right now than any time that I’ve seen. I think ICE [the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement] would be willing potentially to say, “If there’s a church in Indianapolis that would like to receive 30 people, we’ll get them there.” I’m not promising that that could happen. But I think they’re willing to explore. It’s a tangible way for interested churches from around the country to get involved in ways that they haven’t been able to in the past.

So any church could potentially be a host of asylum seekers.

It’s cliché, but every church that hosts feels like they ended up being more blessed by the situation. So many of those who are arriving at our borders have such a deep faith and have had to rely on their faith in ways that the average person in the US hasn’t had to. Almost always when we’re in dialogue, unprompted they’ll say, “I could never have done this if God wasn’t with me on this journey.” And even through the atrocities, murder, sexual assault, brutality, the loss of kids, and all of that, they talk about their faith in God and love for God. God being present with them in the midst of hardship is so clear.

You’ve mentioned root causes of migration. How does the church think about this globally?

There are groups on the ground, in countries all around Latin America, doing incredible work and needing support. There’s a whole network that’s growing of evangelical churches in Colombia who are working with [some of the 2.5 million] Venezuelan refugees there.

A church in New York can support a church in Guatemala that’s doing work in their communities. And maybe they can help two or four or ten families stabilize and be in a situation where they don’t feel like they have to leave.