Hello, fellow wayfarers … Why we always want to “just ask questions” about “the least of these” … What teaching the next generation with music can remind us about the meaning of reality … How I was an idiot (at least once) in last week’s newsletter … A special Bulletin tie-in Desert Island Bookshelf … This is this week’s Moore to the Point.

The “Least of These” and the Quest for a Post-Christian Conscience

Every few years, someone makes the point that, “actually,” the “least of these” passage from the Gospel of Matthew doesn’t really have anything to do with how we treat the poor or the stranger or the hungry.

The “brothers” to which Jesus refers, the argument goes, are the messengers he sent out—meaning that the way one responds to the bearers of Jesus’ word signifies the way one responds to him. It’s not about the poor, the argument goes, but about mistreated fellow Christians.

A friend told me last week that some social media controversy dusted up for a bit over just this question. He needn’t tell me who posted it, because it doesn’t matter in this ephemeral medium—the players always change and the game remains the same.

Anybody who’s ever been a youth pastor knows that there’s a certain kind of question—like “How far is too far?” or “Actually, Jesus wasn’t talking about the kind of sex I want to have”—that’s less about “just asking questions” of the text than about doing what one wants to do.

The text in question here, of course, is a familiar one to those who’ve been in the orbit of the Bible for any time at all. After a series of parables about the kingdom of God, Jesus portrays for his disciples a haunting description of Judgment Day, in which the nations are gathered before Christ the shepherd, who divides the sheep of the redeemed from the goats of the damned.

To both groups, Jesus notes that he had been among them—as hungry, thirsty, naked, imprisoned, a stranger. The sheep, Jesus said, had fed him, given him water and clothing, welcomed him in, visited him in his distress. The goats, Jesus said, had ignored him. Both groups are shocked and ask, “When did we do this?” Jesus responds, “Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me” (Matt. 25:40, ESV throughout).

Even those who believe that “brothers” refers to those whom Jesus sent out with the gospel are quick to say that the point of his teaching is hardly “Which vulnerable people can we safely ignore?” As a matter of fact, under any reading of Jesus’ words, the application is the exact opposite, and it’s hard to imagine how Jesus could have worded it to make the point any stronger.

Suppose, for a moment, that the “brothers” here are, in fact, those whom Jesus sent out. The scene is of the gathering of all the nations—very few of whom would have encountered this relatively small group of people. As a matter of fact, all of those originally sent out are now dead. Are the nations of people outside that small circle now exempt? Of course not.

More to the point, the entire teaching centers on the surprise of both groups—sheep and goats—as to when, in fact, they ever encountered Jesus. The sheep do not respond, “Yes, we know. That’s why we did it. We had the chart telling us which strangers to welcome and which to ignore.” The goats could not have said, “If we’d known they were with you, we, of course, would have given them some porridge!”

The question is about conformity to Jesus himself. This is the one charged, repeatedly, with eating and drinking with those outside the approved definition of “brothers” (Matt. 9:9–13; Luke 19:1–10; John 4:5–26). This is the Jesus who told us that the “friend/enemy” distinction—love those who are “with” you, and hate those who aren’t—is contrary to the kingdom he is announcing. “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy,’” he said. “But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” (Matt. 5:43–44).

The question raised by these sorts of “actually” arguments, about parsing out who fits in the “least of these” and who does not, is not a new one. It is, quite literally, the question Jesus answered from a lawyer seeking to parse out how he was within the bounds of “love God and love your neighbor” with the question, “Who is my neighbor?” (Luke 10:29). One can almost hear the equivocating “Actually, neighbor in the context of the Torah refers to those within the household of Israel, so …”

Jesus deconstructs all of that with a story, choosing the most hated possible example of negative identity politics—a Samaritan—to make the point that the question is not about figuring out how to categorize “neighbor” but about how to be a neighbor, by showing mercy and compassion (vv. 36–37).

The entire canon makes the case that our response to the poor does indeed tell us something about our response to God. “Whoever is generous to the poor lends to the Lord, and he will repay him for his deed,” and “whoever closes his ear to the cry of the poor will himself call out and not be answered,” the Bible says (Prov. 19:17; 21:13).

The Psalms repeatedly argue that the fatherless, the widows, the strangers, those deemed too powerless to matter, have a God who knows and hears them and who will plead their case (Ps. 68:5). The prophets make the point that the ill treatment of the vulnerable—the poor, orphans, widows—makes worship noxious in the presence of God (Isa.1:14–17).

Jesus’ own brother, James of Jerusalem, likewise argues that landowners robbing their workers of wages is an offense to God because “the cries of the harvesters have reached the ears of the Lord of hosts” (James 5:4).

Why else have Christians—from the first century—cared for unwanted children and opposed abortion and infanticide? Our treatment of the vulnerable reveals what we think about God, for the vulnerable are made in his image too. The idea that some people are disposable because of their lack of value by the world’s categories of power and wisdom is directly opposed to Christ and the meaning of the Cross. An assault on human dignity is an assault on the image of God (James 3:9).

And the image of God is no abstraction. The exact image of the radiance of God has a name: Jesus of Nazareth (Col. 1:15; Heb. 1:3). As we do to those who bear that image—even the “least” of them—we have done unto him.

Does that resolve all of our prudential arguments about how best to care for the poor when it comes to governmental systems and policies? Of course not. It does not answer every question about how best for you, personally, to address the needs of those around you. It does mean, however, that when you confront the need of a vulnerable person in need of help, your response is not to ask for their papers. Those who welcome strangers have, at times, entertained angels unaware, the Bible tells us (Heb. 13:2). And the key word there is unaware.

If one is embarrassed by the miracles or morality of Jesus, one can always demythologize him with all the fervor of a 19th-century German scholar. If one is embarrassed by the compassion or empathy of Jesus, one can demythologize him there too, with all the frenzy of a 20th-century German soldier. None of that will change, not one iota, that Jesus is ultimately seated on the throne. Before him, “Has God really said?” is a terrible question to ask. So is “Who is my neighbor?”

And when confronted with the suffering of human beings around you, making the point that those who are suffering are less than the “least of these” is no argument at all.

Why Music Matters for Children

A couple weeks ago, I had dinner in Wheaton, Illinois, with writer, filmmaker, and podcaster Phil Vischer—cohost of The Holy Post and creator of VeggieTales. It was the night of the vice-presidential debate and I was trying to watch the last bit of it in the Uber on the way back to my hotel. The signal wasn’t good enough, so I gave up and started answering text messages instead. As I did, I noticed that I was humming. Only after a few seconds did I realize the tune: “God is bigger than the boogeyman / He’s bigger than Godzilla and those monsters on TV …”

Without ever even thinking about VeggieTales, my subconscious mind had somehow put together Phil with his creation and prompted me to hum along to a song I haven’t heard in decades. It’s not even a Proust-with-the-madeleine sort of reversion to childhood. VeggieTales didn’t yet exist when I was a child. Instead, somewhere in the whirl of rearing our own children back in the busiest time of our lives, we played and heard that song—and, now, even without thinking about it, it’s embedded somewhere in there. This is one of those aspects of God’s creation of human beings that never fails to fill me with awe.

That’s one of the reasons I wanted to talk to my friend Randall Goodgame this week on the podcast. Randall, the creator of the Slugs & Bugs songs, albums, and shows, just released a new project, Scripture Hymnal, which puts passages of the Bible to song for children. We talk about why music works this way and how we can do a better job with allowing it to channel our psyches toward Scripture as persons, as families, and as churches.

You will also hear a bit about the time I made my acting debut with a puppet slug.

You can listen to it here.

I’m an Idiot

Less than an hour after the newsletter went out last week, one Canadian reader let me know by Instagram reply that I am an idiot. This is not, of course, the way the reader put it. The note instead just pointed out that, for some inexplicable reason, I noted for last week’s Desert Island Playlist that the creator of it was from Winnipeg, Ontario. This reader politely noted that this would be like someone speaking of “Biloxi, Georgia” since Winnipeg is, in fact, in Manitoba.

Mea culpa. I don’t know how that happened. Someone please also tell Michael Scott that a concierge is not, in fact, “a Winnipeg equivalent of a geisha” and that he doesn’t need to exchange all that currency at the airport.

Desert island bookshelf

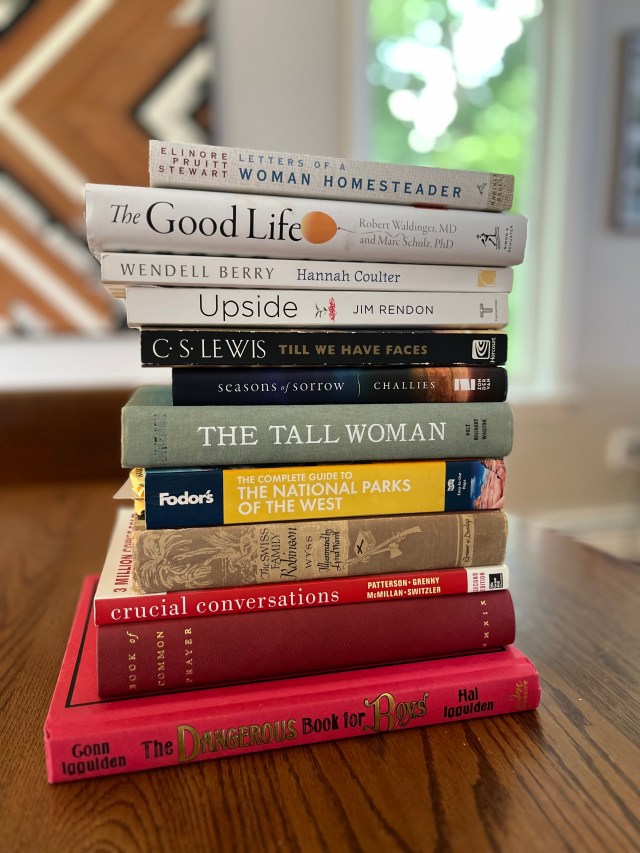

Every other week, I share a list of books that one of you says you’d want to have on hand if you were stranded on a deserted island. This week’s submission comes from reader Clarissa Moll of Boston, Massachusetts, who also happens to be the producer and cohost (along with Mike Cosper and me) of The Bulletin, our weekly news analysis show. She is also the author, along with her daughter Fiona Moll, of the just-released book Hurt Help Hope: A Real Conversation About Teen Grief and Life After Loss (Wander).

Here’s Clarissa’s list:

- Letters of a Woman Homesteader by Elinore Pruitt Stewart: First published in 1913, this classic true story on starting over offers humorous, encouraging companionship to the desert islander who finds herself in a strange new world.

- The Good Life by Robert Waldinger and Marc Schulz: Based on the longest scientific study of happiness, this book will remind you of why relationships matter and why it’s still worth sending those messages in a bottle back home.

- Hannah Coulter by Wendell Berry: Desert life offers lots of time for reflection, and who better to guide you in that contemplation than the wise and winsome Hannah Coulter?

- Upside by Jim Rendon: Lest you be discouraged while marooned alone, journalist Jim Rendon will remind you that resilience after traumatic events isn’t just a possibility; if you work for it, it’s a probability. You can flourish even here!

- Till We Have Faces by C. S. Lewis: No doubt, desert life leaves your heart longing for more. Let Lewis’s allegory draw your heart toward divine love that offers intimacy and companionship beyond compare.

- Seasons of Sorrow by Tim Challies: However you arrived at your desert island, you’re probably grieving something you’ve had to let go. Tim Challies’s honest journey through loss reminds you that even in life’s darkest moments, God is present in our pain.

- The Tall Woman by Wilma Dykeman: This classic Appalachian novel will inspire you to live off the desert land and embrace it as your new home. You can learn to love the place you live.

- Fodor’s The Complete Guide to the National Parks of the West: If your island life inspires wanderlust, there’s no better book for planning a trip!

- The Swiss Family Robinson by Johann David Wyss: If they could do it, you can too! Reach back to your childhood days to gain inspiration for the desert life that lies before you.

- Crucial Conversations by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, Emily Gregory, and Al Switzler. Use your alone time well. Learn to defuse conflict, increase understanding, and become a conversation pro. When you get back to the mainland, your friends and family will thank you.

- The Book of Common Prayer: Sometimes, even on a desert island, life will leave you at a loss for words. These ancient words (with the Psalter included) offer exhortation and consolation that stand the tests of time and place.

- The Dangerous Book for Boys by Hal Iggulden: Before you head to the island, grab this book from your son’s bookshelf. Whether you need to learn to make a bow and arrow or you’ve got some downtime to learn about the game of chess, you’ll find it a practical guide to surviving and staying sane.

Thank you, Clarissa!

Readers, what do y’all think? If you were stranded on a desert island for the rest of your life and could have only one playlist or one bookshelf with you, what songs or books would you choose?

- For a Desert Island Playlist, send me a list between 5 and 12 songs, excluding hymns and worship songs. (We’ll cover those later.)

- For a Desert Island Bookshelf, send me a list of up to 12 books, along with a photo of all the books together.

Send your list (or both lists) to questions@russellmoore.com, and include as much or as little explanation of your choices as you would like, along with the city and state from which you’re writing.

Quote of the Moment

“They tried to pierce your heart with a Morgul-knife which remains in the wound. If they had succeeded, you would have become like they are, only weaker and under their command.”

—Gandalf to Frodo, The Fellowship of the Ring by J. R. R. Tolkien

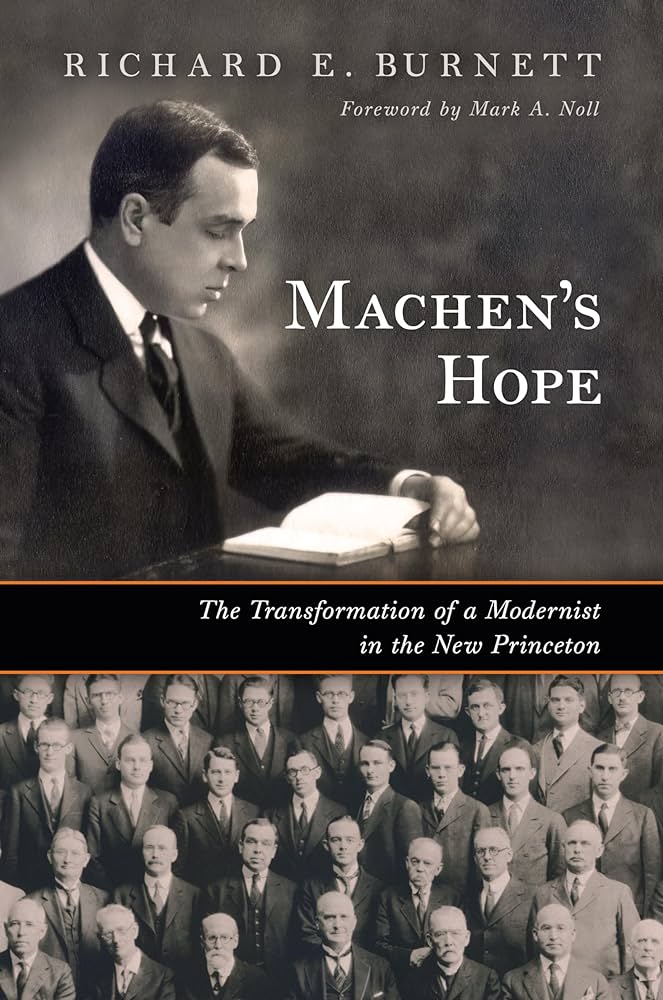

Currently Reading (or Re-Reading)

- Richard E. Burnett, Machen’s Hope: The Transformation of a Modernist in the New Princeton (Eerdmans)

- Thomas Howard, Pondering the Permanent Things: Reflections on Faith, Art, and Culture (Ignatius)

- Peggy Noonan, A Certain Idea of America: Selected Writings (Penguin Portfolio)

Join Us at Christianity Today

Founded by Billy Graham, Christianity Today is on a mission to lift up the sages and storytellers of the global church for the sake of the gospel of Jesus Christ. For a limited time, you can subscribe and get two years for the price of one. You’ll get exclusive print and digital content, along with seasonal devotionals, special issues, and access to the full archives. Plus, you’ll be supporting this weekly conversation we have together. Or, you could give a membership to a friend, a pastor, a church member, someone you mentor, or a curious non-Christian neighbor. You can also make a tax-deductible gift that expands CT’s important voice and influence in the world.

Ask a Question or Say Hello

The Russell Moore Show podcast includes a section where we grapple with the questions you might have about life, the gospel, relationships, work, the church, spirituality, the future, a moral dilemma you’re facing, or whatever. You can send your questions to questions@russellmoore.com. I’ll never use your name—unless you tell me to—and will come up with a groan-inducing pun of a pseudonym for you.

And, of course, I would love to hear from you about anything. Send me an email at questions@russellmoore.com if you have any questions or comments about this newsletter, if there are other things you would like to see discussed here, or if you would just like to say hello.

If you have a friend who might like this, please forward it, and if you’ve gotten this from a friend, please subscribe!

Russell Moore

Editor in Chief, Christianity Today

P.S. You can support the continued work of Christianity Today and the Public Theology Project by subscribing to CT magazine.

Moore to the Point

Join Russell Moore in thinking through the important questions of the day, along with book and music recommendations he has found formative.

Delivered free via email to subscribers weekly. Sign up for this newsletter.

You are currently subscribed as no email found. Sign up to more newsletters like this. Manage your email preferences or unsubscribe.

Christianity Today is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

“Christianity Today” and “CT” are the registered trademarks of Christianity Today International.

Copyright ©2024 Christianity Today, PO Box 788, Wheaton, IL 60187-0788

All rights reserved.