Hello, fellow wayfarers … How a piece of art showed me I wasn’t thinking big enough about the church … Why Stanley Hauerwas told me that recovering a Christian vocabulary is the most important question of the age … A Massachusetts Desert Island Bookshelf … This is this week’s Moore to the Point.

The Glory of the Church Is Between Three Birds

If you wanted to convey to someone in a single image the idea that the church is glorious, holy, and ultimately triumphant, how would you do it?

I suppose you might start with a marketing plan and choose, like any other institution, something to signify trust, strength, and power. Nations, corporations, and even middle school basketball teams adopt symbols such as bears or eagles or rising suns. What you probably wouldn’t choose, however, is the face of a turncoat sobbing with shame.

That’s why I was reluctant to say yes when a colleague pitched a representation of Peter hearing the rooster crow for Christianity Today’s March/April issue cover art. “That’s too negative,” I said. “We want the picture of a bride coming down out of heaven adorned for her husband (Rev. 21:2) or an army awesome with banners (Song 6:10).” Not a shame-faced man after his denial of the Son of God.

It wasn’t until I actually saw the artwork that I realized how wrong I was. Illustrator Aedan Peterson did not soften the agony of the jarringly beautiful scene. One can feel in the posture and visage of the fallen disciple what it would be like to live out Jesus’ words, “Truly, I tell you, this very night, before the rooster crows twice, you will deny me three times” (Mark 14:30). The art prompts the body to feel Peter’s involuntary loss of control at that moment: “And he broke down and wept” (v. 72).

What I missed at first is that this scene really isn’t about the pathos of Peter. It’s about what’s going on in the background behind him: a bird in flight, representative of a struggle that starts at the beginning of the biblical canon and continues all the way to the end.

One bird is never pictured with the scene of Peter’s denial but shows up elsewhere in Scripture: the raven. Ravens are sometimes depicted positively in the Bible, such as in carrying food to the starving prophet Elijah to sustain him in his desert escape from Ahab and Jezebel (1 Kings 17:4–6).

But there’s a reason Edgar Allan Poe chose a raven to deliver the ominous line “Nevermore” in his unnerving poem. In Scripture, ravens are pronounced unclean, and the people of Israel are forbidden to eat them (Deut. 14:14), because the birds are carrion eaters. To see a raven, as to see a vulture, is to see a sign of the presence of death.

After the Flood, the first bird that Noah sent out as an intelligence-gathering operation was a raven, which went, Genesis tells us, “to and fro until the waters were dried up from the earth” (8:7). The raven could survive capably in such a situation—with corpses everywhere on which to feed.

Peter did not see a literal raven in his moment by the fire, but he did see the omen of death. One of the indignities and horrors of crucifixion in the Roman world was that those left on the crosses would often be eaten by scavenging birds. In the arrest of Jesus, Peter could see such a future for himself.

Literary scholar Erich Auerbach once described this scene as revolutionary and unprecedented in the literature of the time: the depiction of the emotional anguish not of a hero or king or god but of a common fisherman. The Eastern Orthodox theologian David Bentley Hart wrote too that this scene must have “seemed to its first readers to be an aesthetic mistake; for Peter, as a rustic, could not possibly have been a worthy object of a well-bred man’s sympathy, nor could his grief possibly have possessed the sort of tragic dignity necessary to make it worthy of anyone’s notice.”

Peter’s anguish and hopelessness in the face of death—that of his rabbi and likely his own—is crucial to his story of denial, included in all four Gospels. After all, when told of Jesus’ impending crucifixion, Peter’s first response was to rattle his swords. “Far be it from you, Lord! This shall never happen to you,” Peter said (Matt. 16:22). Peter saw the defeat of the Messiah by Rome to be a hindrance to the plan of the dawning of the kingdom of God, on earth as it is in heaven.

But Jesus said that Peter’s bravado was actually the hindrance—that it was carnal, even satanic (v. 23). Jesus continued, “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it” (vv. 24–25).

When Jesus is arrested, Peter’s first response is violence—to follow the way of the raven toward the death of his enemies, cutting off the ear of the servant of the high priest, earning once again a rebuke from Jesus: “Put your sword back into its place. For all who take the sword will perish by the sword” (26:52).

Crouched over the charcoal fire, Peter later tries to hide his Galilean background and his affiliation with the teacher out of a sense of self-protection. He doesn’t want to die. And that’s when he hears the call of another bird.

The crowing of the rooster is about more than just one man, even a man as significant as the apostle Peter, who was the first to confess Jesus as “the Christ, the Son of the living God” (16:16). Jesus gave him a name that meant “rock” to convey stability, fortitude, and dependability, saying, “Upon this rock I will build my church and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it” (v. 18).

With a name like that, we might wish to see a heroic, stalwart Peter as a model for us that we too can hold fast as the people of God. But if that’s what Jesus had shown us, we could not survive the shaking of the church. We would lose heart. We might even doubt that the church could withstand a time of secularization, dechurching, repetitive scandal, and scary global threats.

Where are the rock-like pillars of stability who can take us there? All we have are weak, fumbling Christians like us, who know how many times we have said to the outside world with our thoughts or actions or fear, with our lack of love or faith or hope, “I do not know the man” (26:74). We are not heroes, and we have none around us.

The cry of the rooster was one of the most familiar sounds in the life cycle of a first-century person, as common as the sound of an iPhone alarm is to us. It would probably have had the same effect then as it does now, causing the person hearing it to initially grumble.

We want to stay asleep, but the rooster’s cry is to wake us up. And part of what Peter had to hear is that he is not as strong as he thought he was. Neither are we. That’s why the sound of the rooster’s crowing—as painful as it is to hear—is actually grace.

The reason Peter wept when he heard that chicken’s call is that Jesus had told him ahead of time that this sound would coincide with Peter having denied him three times. If we get what’s really happening here, it can change everything.

If Jesus had simply nodded at all of Peter’s vows of commitment to the death, Peter would have had reason, after he had fallen into what he said he would never do, to despair. He would have thought that Jesus’ commitment to him was based on Peter’s own performance, on his own heroism. He would have believed that Jesus had simply thought him to be stronger or more faithful than he actually was.

But Jesus knew what would happen before the rooster crowed. And even knowing Peter’s fragility and flaw, Jesus said to him, in the same scene, “I have prayed for you that your faith may not fail. And when you have turned again, strengthen your brothers” (Luke 22:32).

That’s, of course, exactly what Peter does. Jesus meets Peter after his resurrection—at the very same setting of a charcoal fire—not to rebuke him but to reaffirm his love.

The rooster is there, representing all the ways we fumble and fall and fail, but the rooster’s crow is not the final sound. If you look closer at the March/April cover, you will see another bird. On the pillar behind the scene is the shadow of a dove. The raven had followed Peter all his life—“Satan demanded to have you, that he might sift you like wheat” (v. 31)—but so had the dove.

The dove, remember, was the second bird that Noah sent from the ark. The dove first brought back a branch—a sign of life on the other side—and then it didn’t return at all, having found a place to rest beyond the wreckage of judgment.

At Jesus’ baptism, which is his sign of solidarity with us sinners in the judgment we deserve, the Bible tells us that he saw “the Spirit of God descending like a dove and coming to rest on him; and behold, a voice from heaven said, ‘This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased’” (Matt. 3:16–17).

That dove of the Spirit would descend once more after Jesus’ resurrection: on the disciples gathered in Jerusalem at Pentecost, giving birth to the church (Acts 2:1–21). The dove—like the one Noah once sent out from the ark—returns with signs of life, holding a branch from the Tree of Life in the new creation, beyond all we can see or imagine.

Crucially, this Spirit is not a reward for good behavior or heroic deeds. At Pentecost, it fell on a church filled not with geniuses and strategists but with fishermen and peasant women. And who was standing there announcing that a new day had dawned? Who was the first recorded to bear witness that day? Simon Peter, not one bit afraid to say the word Jesus over and over and over again (vv. 14–41).

That’s why we remain confident that the church we love will triumph. The raven broods and the rooster struts, but the dove descends.

The raven is an omen of the death and destruction around us. The rooster is an announcement of the dawn of another day, the day after we have failed yet again to live up to all our bluster.

The dove is less visible, less noticeable, except to the eyes of faith. But in its mouth, there’s a branch that shows there’s a new world on the other side of it all.

Stanley Hauerwas Still Thinks Jesus Changes Everything

Years ago, one of my fellow evangelicals told me they were going to invite Stanley Hauerwas to speak at their (very conservative) institution. He needed some advice on how to keep the notoriously iconoclastic theologian/ethicist from doing one thing: cussing.

He knew that his constituency wouldn’t mind having a different viewpoint represented—even that of a pacifist like Hauerwas—but they wouldn’t stand for hearing a speaker do what Hauerwas had done in countless venues as well as in print: let loose with a salty word or two.

At that time, I had never met Stanley Hauerwas (and wouldn’t for another almost quarter century), but I had read him for years and felt I could give this advice: “Invite him or don’t invite him, but I think if you tell him what not to say, it’s likely to make him want to say it.”

I can’t remember whether he cussed at that event, but either way, they all survived. And I think my assessment of Hauerwas’s refusal to be censored still stands.

On this week’s episode of the podcast, professor Hauerwas joins me. He doesn’t cuss, but he does tell me where he thinks I’m wrong on the justness and necessity of some wars (such as World War II). We also agree on a lot of other things—that the church should be a colony of the kingdom, that believers should be “resident aliens,” that the Christian story makes sense of the world, and that a Christian vocabulary “works.”

You can listen to our conversation here.

Desert island bookshelf

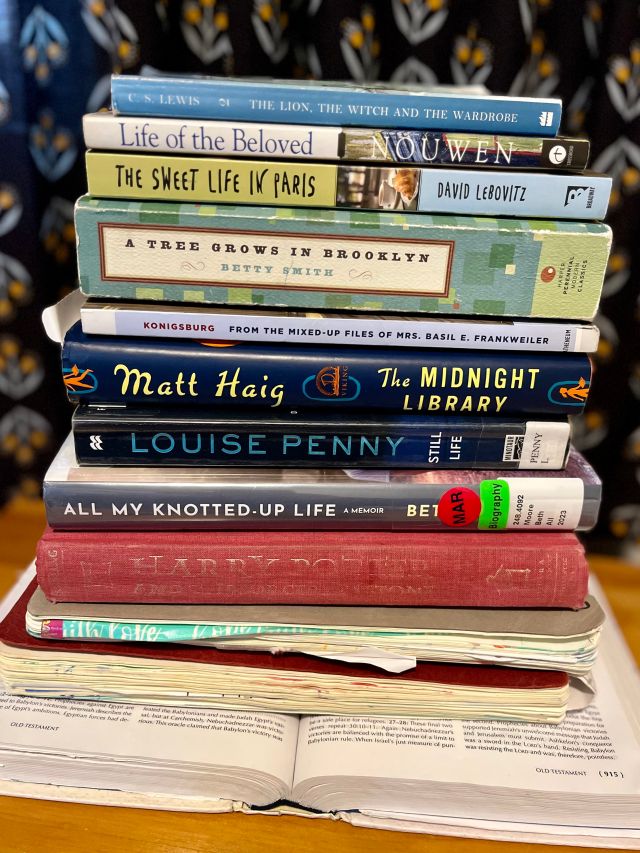

Every other week, I share a list of books that one of you says you’d want to have on hand if you were stranded on a deserted island. This week’s submission comes from reader Andrea Marshall, a spiritual director from Natick, Massachusetts.

Andrea writes:

Your invitation to send in the Desert Island Bookshelf grabbed my attention and became a beautiful task for this dreary day. I have misplaced a few of my well-worn copies, so I had to improvise and use the local library for two of my picks. I am a huge fan of libraries, so no harm there.

Andrea says that she would be “lost without this collection,” and she’s even titled it with a quote: “The world was hers for the reading” (Betty Smith). Here’s Andrea’s bookshelf, with which she included a quote from each one:

- A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith: “‘Dear God,’ she prayed, ‘Let me be something every hour of my life.’”

- From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E. L. Konigsburg: “Therefore, she decided that her leaving home would not be just running from somewhere but would be running to somewhere.”

- Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J. K. Rowling: “Harry found that he had fewer nightmares when he was tired after working out.”

- Still Life by Louise Penny: “‘There are four things that lead to wisdom. You ready for them?’ She nodded, wondering when the police work would begin. ‘They are four sentences we learn to say, and mean.’ Gamache held up his hand as a fist and raised a finger with each point. ‘I don’t know. I need help. I’m sorry. I was wrong.’”

- Life of the Beloved by Henri Nouwen: “The real ‘work’ of prayer is to become silent and listen to the voice that says good things about me. To gently push aside and silence the many voices that question my goodness and to trust that I will hear the voice of blessing—that demands real effort.”

- The “Mom” Book, volumes 1 and 2, by Holly and Benjamin Lukas: Collections of poems, drawings, letters given to me since the day they were born. After my children themselves, this would be the first grab in a house fire.

- The Bible, New Living Translation: “Those who live in the shelter of the Most High will find rest in the shadow of the Almighty. This I declare about the Lord: He alone is my refuge, my place of safety; he is my God, and I trust him” (Psalm 91:1–2).

- All My Knotted-Up Life: A Memoir by Beth Moore: “Jesus is the only outsider who truly knows the insider our skin keeps veiled.”

- The Sweet Life in Paris by David Lebovitz: “Paris has a way of making even the simplest of things feel extraordinary.”

- The Midnight Library by Matt Haig: “Love and laughter and fear and pain are universal currencies.”

- The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe by C. S. Lewis: “‘Safe?’ said Mr. Beaver. ‘Don’t you hear what Mrs. Beaver tells you? Who said anything about safe? ’Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.’”

Thank you, Andrea!

Readers, what do y’all think? If you were stranded on a desert island for the rest of your life and could have only one playlist or one bookshelf with you, what songs or books would you choose?

- For a Desert Island Playlist, send me a list between 5 and 12 songs, excluding hymns and worship songs. (We’ll cover those later.)

- For a Desert Island Bookshelf, send me a list of up to 12 books, along with a photo of all the books together.

Send your list (or both lists) to questions@russellmoore.com, and include as much or as little explanation of your choices as you would like, along with the city and state from which you’re writing.

Quote of the Moment

“I grew up irreligious and argumentative and materially minded and then something, in my forties, went to work on me. I said earlier that I sometimes feel I am being called. Now that I’ve written myself through this thing, whatever it is, that feeling is even clearer. But what does it mean? I don’t know. What could be calling me? I don’t know. What I do know is that when you give your words permission to access that boiling lake, to dig down beneath the shores of reason, to look out at the terrible madness and beauty of the universe or into the Gorgon’s eyes or down into the abyss, then you are in danger of unleashing something you can’t control. It’s like playing with a Ouija board, or visiting a cabin in the woods with your teenage friends in an American horror film. You muck about with these things at your peril. If you open those doors, you have to know how to close them again.”

—Paul Kingsnorth (2019)

Currently Reading (or Re-Reading)

- Albert Camus, Resistance, Rebellion, and Death: Essays, trans. Justin O’Brien (Random House)

- Timothy Paul Jones, Did the Resurrection Really Happen? (Crossway)

- Paul Kingsnorth, Savage Gods (Two Dollar Radio)

- Ryan P. Burge, The American Religious Landscape: Facts, Trends, and the Future (Oxford University Press)

Join Us at Christianity Today

Founded by Billy Graham, Christianity Today is on a mission to lift up the sages and storytellers of the global church for the sake of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Subscribe now to get exclusive print and digital content, along with seasonal devotionals, special issues, and access to the full archives. Plus, you’ll be supporting this weekly conversation we have together. Or, you could give a membership to a friend, a pastor, a church member, someone you mentor, or a curious non-Christian neighbor. You can also make a tax-deductible gift that expands CT’s important voice and influence in the world.

Ask a Question or Say Hello

The Russell Moore Show podcast includes a section where we grapple with the questions you might have about life, the gospel, relationships, work, the church, spirituality, the future, a moral dilemma you’re facing, or whatever. You can send your questions to questions@russellmoore.com. I’ll never use your name—unless you tell me to—and will come up with a groan-inducing pun of a pseudonym for you.

And, of course, I would love to hear from you about anything. Send me an email at questions@russellmoore.com if you have any questions or comments about this newsletter, if there are other things you would like to see discussed here, or if you would just like to say hello.

If you have a friend who might like this, please forward it, and if you’ve gotten this from a friend, please subscribe!

Russell Moore

Editor in Chief, Christianity Today

P.S. You can support the continued work of Christianity Today and the Public Theology Project by subscribing to CT magazine.

Moore to the Point

Join Russell Moore in thinking through the important questions of the day, along with book and music recommendations he has found formative.

Delivered free via email to subscribers weekly. Sign up for this newsletter.

You are currently subscribed as no email found. Sign up to more newsletters like this. Manage your email preferences or unsubscribe.

Christianity Today is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

“Christianity Today” and “CT” are the registered trademarks of Christianity Today International.

Copyright ©2025 Christianity Today, PO Box 788, Wheaton, IL 60187-0788

All rights reserved.