Hello, fellow wayfarers … How teaching through the Book of Revelation kept me sane in this crazy year … Why our real problem is panic—and where we can find the way out of it … What Charlie Peacock taught me about music and how to pursue one’s calling without burning out or giving up … A Lonestar Desert Island Playlist … This is this week’s Moore to the Point.

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Apocalypse

When times are dark, people often steady themselves with an escape into a book. Sometimes that means retreating into stories of simpler times or happier places. I recently learned there’s even a genre called “cozy mystery.”

With the bleakness of the news these days, I too found myself seeking refuge in the better, calmer world of a book. The weird thing is that the book is Revelation.

When I first considered teaching through Revelation at my church, I had some qualms. People everywhere are already on edge—reeling from a pandemic, divided by politics, staring down an artificial intelligence revolution that might upend everything—and Revelation is, well, apocalyptic.

Its symbology of beasts, dragons, horsemen, and seals can seem confusing and overwhelming to most people. Plus, the Book of Revelation can be terrifying. It opens with the resurrected Christ sternly rebuking churches, and then gets darker.

I love the book, but I wondered if teaching it in this current moment would feel like showing up to a Sex Addicts Anonymous retreat to lead a study on Song of Solomon.

Maybe I should wait for a less chaotic time, I said to myself. But I’m glad I resisted that temptation to quit before I started. Spending time each week in Revelation—meditating on it, preparing to teach it—has calmed me, steadied my nerves, and even made me happier. Here’s why.

Many treat Revelation as a cryptic message meant for someone else. Some think it was for first-century Christians under Roman persecution. Others, especially in the past century of American Christianity, believe it’s a roadmap for the end times: Wormwood is satellite technology, the mark of the Beast is a QR code, Gog and Magog are China and Russia, and so on.

But Revelation, like all Scripture, is Christ speaking to his church in every generation, in every kind of crisis. Those who have paid close attention to the book across history often identify two central themes: unveiling and overcoming. Both speak directly to my temptations toward cynicism and anxiety, and both offer surprising comfort.

Unveiling, the literal meaning of apocalypse, doesn’t mean vindication. In a time when truth is often defined by power or popularity—even by those who once warned against relativism—many measure truth by the “vibe” or the proximity to influence, whether that’s corporate hierarchies or tech algorithms. In this framework, truth becomes whatever wins in the moment.

Social media and entertainment culture have reinforced the illusion that truth is what goes viral. If a church is growing, it must be faithful. If a political movement polls well, it must be right. In personal conflicts, many assume there will eventually be a moment when the truth comes out and finally vindicates them. But that moment rarely arrives.

The unveiling in Revelation is different. It reveals a deeper reality than metrics. Jesus says to the churches, “I know.” “I know where you dwell, where Satan’s throne is. … You did not deny my faith,” he tells one (2:13, ESV throughout). To another: “You have the reputation of being alive, but you are dead” (3:1).

The Roman Empire appeared to be the apex of history, the ultimate civilization. Yet Revelation unmasks it. What looks like a god is a beast (ch. 13), and Babylon, which seems permanent, collapses in an hour (18:10).

The Christians pressured to conform seem like a scattered, feeble minority, but they are actually part of “a great multitude that no one could number” (7:9). The throne that crucifies them is occupied by a beast, but behind the veil sits a “Lamb who was slain” (5:12).

Overcoming, the other dominant theme, answers the question that haunts many of us: “Yes, but what can we do?” Revelation answers, again and again: Overcome. But not in the way we expect.

The overcomers are not the ones who conquer Rome or subvert Babylon. They are those who refuse to bow. They do not triumph by redirecting the same kind of power for “our side” but by resisting those categories for “winning” altogether. “They have conquered him by the blood of the Lamb and by the word of their testimony, for they loved not their lives even unto death” (12:11).

In Revelation, the real threat to the church isn’t persecution—it’s assimilation. “Do not fear what you are about to suffer” (2:10), Jesus says to one church. The danger is not what the empire can do to Christians, but what Christians will become to avoid suffering.

Jesus downplays external threats, urging endurance. But he warns severely against internal compromise. To lose your life is bearable. To lose your lampstand is not. To be without a head is temporary. To be without Jesus is hell.

When we ask, “What can we do?” in the face of overwhelming evil, we often want a strategy. Sometimes that’s possible and necessary. But more often, the problems are too vast to solve by technique.

You can’t fix “the church.” You can’t save “the world.” But you can call cruelty what it is. You can see idolatry clearly. You can refuse to become a Beast yourself. And Revelation shows us that what stands against the Beast is not a bigger, stronger beast—but a Lamb that is slain.

The unveiling in Revelation is a call to wisdom. “He who has an ear, let him hear what the Spirit says to the churches” (3:6). And the theme of overcoming in Revelation is a call to endurance. It is better to be beheaded than to become a beheader.

Yes, the times are perilous. They always are. Maybe there’s war, famine, or tyranny on the horizon. But behind the veil, the table is being set for a wedding feast. That should strengthen us to stand without fear or despair. It should remind us of the way back to the Tree of Life.

Apocalyptic questions demand apocalyptic answers: Stay awake. Strengthen what remains. Learn to say, “Come, Lord Jesus.” Overcome.

And when you feel anxious or afraid, read something calming and reassuring—like the Book of Revelation.

On the Problem of Panic

The May/June issue of Christianity Today is out this week, and I would encourage you to subscribe to see all of it plus other amazing stuff. Here’s part of what I had to say in the issue in an essay called “The Problem of Panic”:

A decade ago, I led a van full of American Christians on a tour of the biblical sites in Israel and Palestine. I couldn’t wait to show them one of my favorite places there: the mountains of what was once known as Caesarea Philippi. There, Jesus said to Peter, “On this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it” (Matt. 16:18).

As I walked with my tour, I noticed a small group of Europeans dressed in all black, huddled together and murmuring as they looked at the ground. “Are they praying?” I asked our Israeli tour guide.

He laughed and rolled his eyes. “Well, kind of,” he said. “Sometimes Neopagans want to come here because, you know, this used to be a special place for that kind of thing. This is where they once worshiped the god Pan.”

Secularization isn’t evaporating spirituality but rather is rechanneling it, as cultural observers such as Tara Isabella Burton have documented. People, like the Pan worshipers, are finding new spiritual tribes and self-styled rituals and practices, with some seeking to reclaim the “old gods” of ancient paganism.

Part of the attraction is that these spiritualities appear ancient but are also free from any traceable organizational history. Much of the disillusionment with institutions today is due to those organizations’ failures to live up to their own ideals. These spiritualities, on the other hand, have ideals without having to show historically how they impacted structures and communities.

The tour guide made fun of the modern-day Pan worshipers. “It’s all just made up, you know,” he said. “There are no real pagans left. Pan has been dead a long time, and he isn’t coming back.”

The European pop-pagans may have been piecing together a “made-up” spirituality, but they weren’t wrong about part of the meaning of that location. The place is known to Christians as Caesarea Philippi, but its modern name is Banias, an Arabic version of Panias, after the god Pan. The significance of the varied meanings of this place was highlighted in 2020 when an archaeological dig uncovered an ancient Christian church beneath the site dating to the AD 400s.

This is not surprising. After all, it would make sense to build a church where Jesus promised to do so—upon the rock. But the archaeologists found underneath that church yet another structure of worship, this one dating back to about 20 BC: a temple to the god Pan. A scholar explained to the press that the worship of Pan had happened in that place since at least 300 years before Christ.

When Jesus spoke to Peter in Matthew 16, he did so over this ancient site of Pan. Perhaps no chapter in the Bible is more evocative of our current crisis—and not for the reasons many Christians think.

Handwringing believers will cap off some expression of panic with the words from verse 18, saying, “But we know that Jesus said the gates of hell will not prevail against the church.” This is usually spoken as a kind of forced hopefulness, similar to telling a grieving widow at a funeral, “Well, at least your husband’s not in pain anymore.” But in so doing, we do to these words what we have too often done to other majestic passages: turn them into decontextualized slogans and thus empty the words of their power.

The truth is that what Jesus said matters as much as where he said it. When Jesus stood in Caesarea Philippi and spoke in Matthew 16:13–28, he knew this was a place of panic, of devotion to the god of the pulsing libido and the raging fist. He also knew that this place now belonged to the house of Herod, whose son Philip named it after himself and the Roman emperor. The place represented what again seem to be opposite poles—the chaos of natural wildness and the control of political power, the panic of nature and the panic of history.

But Jesus recognized that human power and natural wildness are not separate things. They are one. The power of Caesar that crucified Christ is represented later throughout the Book of Revelation as humanity aspiring to ultimate, godlike power and control. But in so doing, the truth of Caesar is revealed to be wild and animalistic—in fact, a beast.

Jesus revealed his own power at Caesarea Philippi. But his power is starkly different from both the way of Caesar and the way of Pan.

Here’s a gift link to read the whole essay. While you’re at it, you can join up with us and subscribe here.

Humble as a Peacock

Is God’s will for your life more of a dot or a circle?

That’s one of the questions I explored this week over on the podcast with Grammy Award–winning producer and artist Charlie Peacock, whose new memoir Roots & Rhythm explores what it means to find one’s calling in life, how to heal from the past, and how to give up the quest for holding on to power.

Our conversation reveals at least one middle-school-era debate over what counts as “Christian music” (spoiler: there was almost a fistfight over Amy Grant, and it wasn’t Charlie in the conflict). We also talk about fame, ambition, and why some people burn out while others grow deeper in their callings with time. I also, for a brief moment, psychoanalyze Charlie’s choice of “Peacock” as a stage name.

Charlie discloses a lot of stories behind producing music for Amy Grant, Switchfoot, and The Civil Wars—and what he’s learned from the visible economies of success and the hidden “great economy” about which Wendell Berry wrote.

You’ll hear thoughtful conversation on everything from Zen Buddhism and Jack Kerouac to artificial intelligence and the future of music. Along the way, Charlie reflects on a note found after his mother’s death, a formative encounter with Kierkegaard, and what it means to live with grace as an antidote to karma. We also talk about Frederick Buechner and Merle Haggard, as well as fatherhood, how to find a “circle of affirmation,” and why failing is as important as succeeding.

I loved this conversation and would have liked to have talked for hours more.

If peacock means pride and performance, Charlie is poorly self-named—at least the grown-up version of Charlie now. But if peacock means, as it did in some traditions, resurrection and new life, then it fits just fine.

You can listen to our conversation here.

Desert island bookshelf

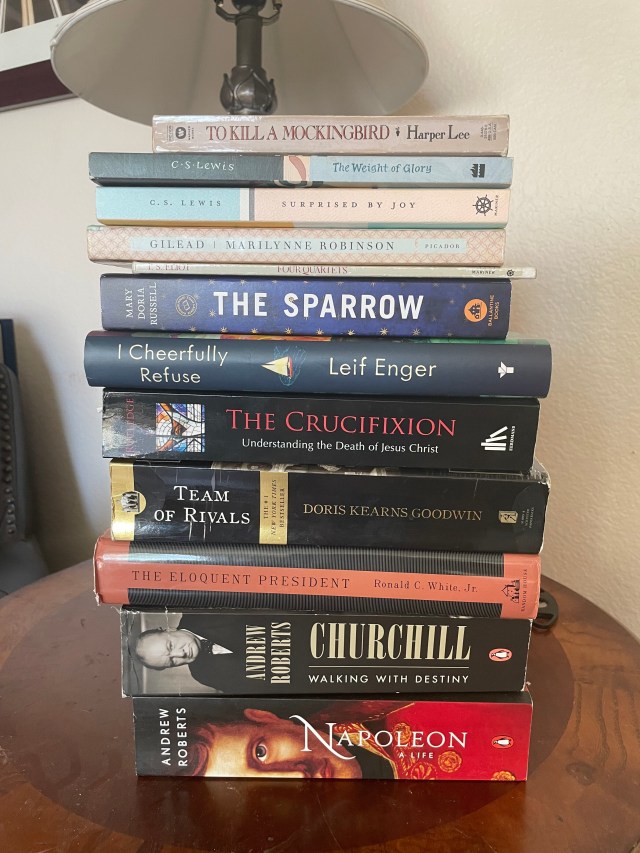

Every other week, I share a list of books that one of you says you’d want to have on hand if you were stranded on a deserted island. This week’s submission comes from reader Clayton Ransom from McKinney, Texas:

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee: This is my favorite book of all time. It has only become more meaningful as I have become a father.

- The Weight of Glory by C. S. Lewis: Some of Lewis’s best thoughts in one volume and deep enough to reward rereading.

- Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life by C. S. Lewis: This book can be summed up by the lyrics of The Gray Havens’ song “Far Kingdom”: “Still there is more gladness / Longing for the sight / Than to behold or be filled, by anything.”

- Gilead by Marilynne Robinson: I find John Ames gives voice to many of the thoughts I can’t put words to. So rich and moving.

- Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot: “… distracted by distraction from distraction …”

- The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell: Job meets Interstellar. At once a theodicy and an intense sci-fi story.

- I Cheerfully Refuse by Leif Enger: I have not read anything that has made me so sad and yet so hopeful at the same time, except maybe the Bible.

- The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ by Fleming Rutledge: Someone recently said on here that it would take a lifetime to unpack this book and the event of the death of Christ. Seems like a worthy endeavor on an island all alone.

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln by Doris Kearns Goodwin: Lincoln is a favorite of mine, and this book captures so many of the facets of the man. Also, even though I knew the ending, I cried when he died. That’s just good writing.

- The Eloquent President: A Portrait of Lincoln Through His Words by Ronald C. White Jr.: Phrases like “the silent artillery of time” and “mystic chords of memory” fill Lincoln’s most famous speeches. I will want words like that on the island.

- Churchill: Walking with Destiny by Andrew Roberts: My favorite volume on another man who had a way with words.

- Napoleon by Andrew Roberts: Not just interesting but he found his way off of one island only to die on another. Figure he will be good company.

Thank you, Clayton!

Readers, what do y’all think? If you were stranded on a desert island for the rest of your life and could have only one playlist or one bookshelf with you, what songs or books would you choose?

- For a Desert Island Playlist, send me a list between 5 and 12 songs, excluding hymns and worship songs. (We’ll cover those later.)

- For a Desert Island Bookshelf, send me a list of up to 12 books, along with a photo of all the books together.

Send your list (or both lists) to questions@russellmoore.com, and include as much or as little explanation of your choices as you would like, along with the city and state from which you’re writing.

Quote of the Moment

“The Sons and Daughters of Adam and Eve were brought out of their own strange world into Narnia only at times when Narnia was stirred and upset, but she mustn’t think it was always like that.”

—C. S. Lewis, The Last Battle

Currently Reading (or Re-Reading)

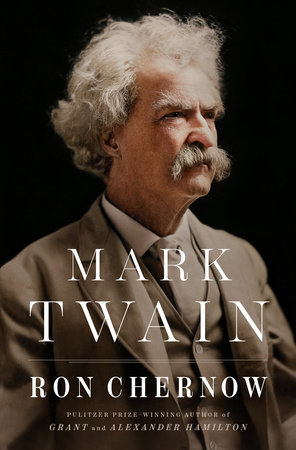

- Ron Chernow, Mark Twain (Penguin)

- Laurence Rees, The Nazi Mind: Twelve Warnings from History (PublicAffairs)

- Joseph L. Mangina and David Ney, eds., Figural Reading and the Fleshly God: The Theology of Ephraim Radner (Baylor University Press)

- Amy Lemco, Wading In: Desegregation on the Mississippi Gulf Coast (University Press of Mississippi)

Join Us at Christianity Today

Founded by Billy Graham, Christianity Today is on a mission to lift up the sages and storytellers of the global church for the sake of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Subscribe now to get exclusive print and digital content, along with seasonal devotionals, special issues, and access to the full archives. Plus, you’ll be supporting this weekly conversation we have together. Or, you could give a membership to a friend, a pastor, a church member, someone you mentor, or a curious non-Christian neighbor. You can also make a tax-deductible gift that expands CT’s important voice and influence in the world.

Ask a Question or Say Hello

The Russell Moore Show podcast includes a section where we grapple with the questions you might have about life, the gospel, relationships, work, the church, spirituality, the future, a moral dilemma you’re facing, or whatever. You can send your questions to questions@russellmoore.com. I’ll never use your name—unless you tell me to—and will come up with a groan-inducing pun of a pseudonym for you.

And, of course, I would love to hear from you about anything. Send me an email at questions@russellmoore.com if you have any questions or comments about this newsletter, if there are other things you would like to see discussed here, or if you would just like to say hello.

If you have a friend who might like this, please forward it, and if you’ve gotten this from a friend, please subscribe!

Russell Moore

Editor in Chief, Christianity Today

P.S. You can support the continued work of Christianity Today and the Public Theology Project by subscribing to CT magazine.

Moore to the Point

Join Russell Moore in thinking through the important questions of the day, along with book and music recommendations he has found formative.

Delivered free via email to subscribers weekly. Sign up for this newsletter.

You are currently subscribed as no email found. Sign up to more newsletters like this. Manage your email preferences or unsubscribe.

Christianity Today is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

“Christianity Today” and “CT” are the registered trademarks of Christianity Today International.

Copyright ©2025 Christianity Today, PO Box 788, Wheaton, IL 60187-0788

All rights reserved.