Hello, fellow wayfarers … How a YouTube atheist convinced me of my own cynicism … Whether we should say please and thank you to robots … Where David Brooks thinks we should look to combat nihilism … A Garden State Desert Island Bookshelf … This is this week’s Moore to the Point.

Cynicism Is Killing Us. Maybe a YouTube Atheist Can Help.

When a Christian friend texted me an interview with Alex O’Connor, I expected my reaction to be an eye-rolling “Can you believe this guy?”

O’Connor—whether technically atheist or agnostic—is one of the most prolific YouTube/podcast skeptics of religion today. More than once, the algorithms have fed me video clips of the 26-year-old cynically dismissing the “superstitions” of Christians and the Bible. So I expected more cynicism, but then was surprised to realize that I was actually the cynical one. The clip moved me and prompted me to examine my own heart.

O’Connor, host of the Within Reason podcast, with over a million subscribers, was in conversation with host André Duqum on the Know Thyself podcast, which seems to be on the New Age side of the “spiritual but not religious” spectrum.

In the clip—excerpted from a much longer conversation—O’Connor displayed a kind of vulnerability quite rare for a person who has built his platform on confidence and rationalism. He confessed a pull toward cynicism, and said he didn’t like where it had taken him:

The person who looks at everything with a sharp edge and tries to debunk and criticize everything—it’s easy and it’s doable and I’ve certainly been there. I know in my family, when I was living at home, it was sort of constant. And you can always fall back on this idea of “I’m just trying to get to the truth. You said something I don’t think is true, and I’m just asking you a question. I’m just trying to understand your view.”

“But sometimes it is just inappropriate to do that,” O’Connor continued. “The intellect is like a knife or a chisel that you can use to tear away at false stuff, but you’re supposed to do it in the service of creating sculpture. You’re supposed to be bringing something out of whatever you’re chiseling away at.”

“If you take that chisel and just knock it all the way down through,” he said, “then you end up with nothing. … It’s like somebody trying to understand the Mona Lisa by looking through a microscope at the paint strokes.”

O’Connor then pointed to the famous philosophical thought experiment of a patient named Mary, who has lived all her life in a completely black-and-white environment, having seen no color at all. She’s been given voluminous factual information on the color blue, “about the wave length, about the effect it has on the consciousness—everything that could be even known and written down onto paper about blue.”

“The question is, when she steps outside of that room and looks at something blue, has she learned anything?” O’Connor asked. “And intuitively the answer is yes. Surely there is something that you can know that is not reducible to words on paper.”

O’Connor confessed that thinking this way—recognizing forms of knowledge that are non-propositional—is not easy for him, trained as he is in syllogisms and argument. But he recognized that there’s more to truth than what can be quantified and measured:

I think C. S. Lewis once wrote about how he realized that the problem with his worldview before he became a theist was that he was being asked to take the things that are most unnatural to him—numbers, abstraction—and say that’s the true thing, the thing that’s really there: the math, the syllogism. Whereas the thing that was most real to him—the narrative, the feeling, the experience—that’s the thing that’s wrong and fake and we should be suspect of. It seems like it was kind of the other way around.

This certainly isn’t any kind of conversion story. O’Connor will no doubt be back at the syllogisms this week in cyberspace. He is not at all backing down on his vision of a world without God. But consider the courage it took for him to say what he said—knowing that someone like me would say, “Aha! See! I caught you!”

Yet to do that would take cynicism on my end too. It flattens O’Connor to a collection of arguments rather than seeing him as a human who can image back the mystery of a personal God, a complicated person who can remind me of the things that matter most. Perhaps O’Connor had been cynically trapped in his syllogisms, but my first expectation of him was cynically trapped in somebody’s algorithms.

That’s the problem with so many of our public debates about God and the meaning of life—for Christians as well as for non-Christians. Most of the time, we are just giving Mary another set of facts about the wavelengths of blue.

To some degree, that’s what we must do. Paul debated the skeptics at the Areopagus and in the court of Agrippa. We are dealing, after all, with matters of a God who entered history in space and in time in the person of Jesus, and this “has not been done in a corner” (Acts 26:26, ESV throughout).

At the same time, God is not reducible to syllogisms and testing. If “in him we live and move and have our being” (17:28), then to examine him the way we would quarks or quasars would require godlike perspective, the ability to stand outside of and thus be able to interrogate the one who says, “I am who I am” (Ex. 3:14). The perplexity before a mystery we cannot comprehend is not an obstacle to our discerning the ultimate but rather a necessary first step.

That’s why the vision of God revealed in the Scriptures is quite different from the way we debate God as just another political or philosophical or cultural dispute in order to find who’s the winner and loser of the argument.

The message is to “taste and see that the Lord is good” (Ps. 34:8). When we ask, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” the message doesn’t give us statistics but instead says simply, “Come and see” (John 1:46). We can’t do that standing from the outside, examining good tidings of great joy the way one would a thing or a concept.

As Christians, we lose sight of this. We become cynical, and that cynicism is easy. In a time like this, it can be mistaken for a sign of intelligence. If I assume that everyone is fake, everything is a scam, then I will turn out to be right much of the time. And I will protect myself from the kind of vulnerability in which a Christian can sometimes admit doubting and an atheist can sometimes admit wondering. That leads us to joylessness, to a lack of wonder and awe, without which we cannot remove the veil that shields us from the glory of God (2 Cor 3:18).

Sometimes we get a little glimpse of how hardened we’ve become, how little we expect the Spirit to move in us or in others. Every once in a while, though, someone reminds us. Sometimes, at least once for me, that’s an atheist on YouTube.

How My Amazon Echo Discipled Me

My wife and I disagree very rarely and about very little. But one of those things about which we are irreconcilable is over the Amazon Echo device named Alexa.

Maria wonders why on earth I would willingly put a kind of surveillance device in our house. But I’ve become dependent on the alarm function of it. “Alexa, wake me at six,” I can say at night, and then, the next morning, I can just say to the alarm, “Alexa, stop!”

As a matter of fact, I set the alarm all day: “Alexa, set an alarm for 1:57,” I will say to remind me of a 2 p.m. meeting. When the alarm goes off, I say, again and again all day, “Alexa, stop!”

I set this alarm a few weeks ago to remind me to start a recording on the podcast. I remembered it without the alarm, though, and logged on, forgetting all about it. While chatting with our team, I heard the buzz from the Echo and, being across the room from it, I yelled, “ALEXA, STOP!”

I momentarily didn’t think about the fact that one of our production team members is, in fact, named Alexa, and that she was at that moment talking.

I immediately had to clarify—“Oh, I wasn’t telling you to shut up! I’m talking to a machine!” But I blushed, and then have cringed every time I think of it.

I thought of both Alexas this week as I read Seth Godin—who is much more utopian about artificial intelligence than I am—on whether we should say thank you to Claude or ChatGPT.

He says we should. Yes, we have a problem with people anthropomorphizing AI—see all the people falling in love with chatbots. A lot of it feels chillingly close to Isaiah’s ridicule of idols, when he speaks of the man who chops down a tree, uses it for a fire to bake bread, and then takes the rest of the wood and constructs a god to which he prays (Isa. 44:13–17). As the prophet Jeremiah pointed out, “The idols are like scarecrows in a cucumber field, and they cannot speak; they have to be carried, for they cannot walk” (Jer. 10:5).

But the opposite is a danger too. Godin argues that the way we treat these machines—given their appearance of “personality”—can train us for cruelty or callousness.

Godin gives the example of the way costumed characters at Disneyland and Disney World need security guards now, because people who would never pinch or harass a “real” human being think of the people beneath the suits as just cartoons. The issue, he contends, is not that Claude “knows” whether or not it’s being thanked but that Godin himself can be trained, by the way he speaks to these tools, to simply bark out orders.

“Sometimes, I say please and thank you to Claude,” Godin writes. “Not because I think it can tell, but because I can.”

Should you say thank you to a device? I don’t know.

Should you ask how the way you use your tools shapes the kind of habits you develop, and thus the kind of person you are? Yes.

David Brooks on How to Reclaim Moral Courage

What happens when a movement built on moral seriousness gives way to one powered by cruelty, resentment, and nihilism?

I resonated intensely with my friend David Brooks’s much-discussed essay in The Atlantic, “I Should Have Seen This Coming.” David discussed what happened to the conservative movement and its descent into personality-driven nihilism, from Burkean virtue aspiration to clickbait outrage, from conserving civic institutions to “own the libs” performance art.

I’ve seen the exact same sort of collapse of the moral center, as you know, in the American evangelical movement. So I wanted to talk to him about it in a way that you could listen in our conversation. That’s what this week’s episode of the podcast is about.

David, of course, is a New York Times columnist and the author of many books, including How to Know a Person. In this episode, we moved from diagnosis to a “How then do we live?” pondering of cultural repair and spiritual renewal.

Is there any indication of a coming revival? How would we know if there were? In the meantime, how do we recover a moral vision clear enough to see us through this present darkness? And what role could Christians play in offering a better way?

Along the way, we talk about the legacy of Tim Keller, how we can engage with our unbelieving friends in conversations on spiritual matters, how President Donald Trump’s White House culture is different from past presidents, and whether AI is really going to change American life as much as I think it will. (Spoiler alert: He doesn’t think so.)

If you’re interested in thinking through how to cultivate the kind of moral courage needed to hold fast to what’s good when the center doesn’t hold, you will like this conversation.

You can listen here.

Desert island bookshelf

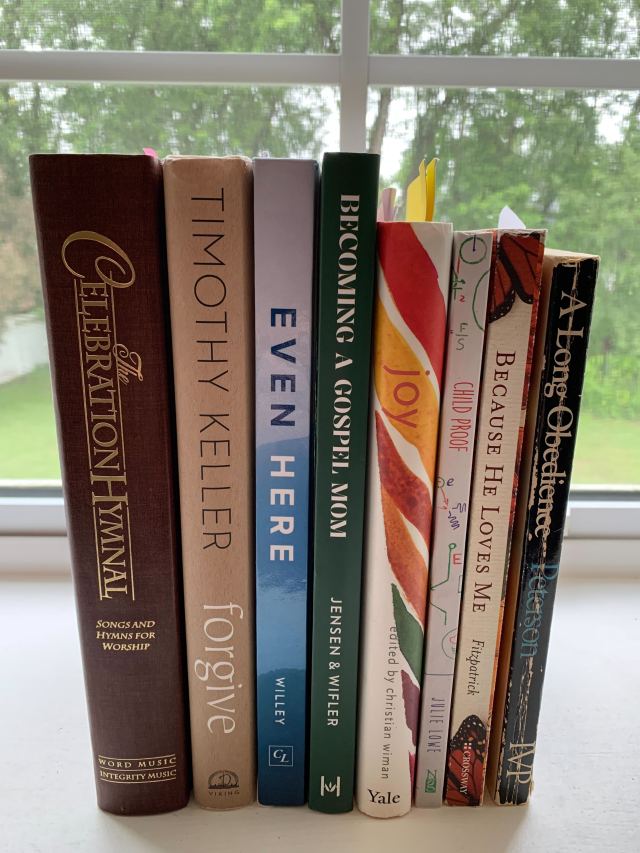

Every other week, I share a list of books that one of you says you’d want to have on hand if you were stranded on a deserted island. This week’s submission comes from reader Kristen Sheppard of Marlton, New Jersey, who wrote that she prefers to imagine her desert island as a Swiss Family Robinson situation, so she chose books her family could enjoy too. She notes that not all books are pictured because she’s “a big fan of the library.”

Here’s her list:

- A Long Obedience in the Same Direction by Eugene H. Peterson: I make it a point to reread this book once every several years.

- Because He Loves Me: How Christ Transforms Our Daily Life by Elyse M. Fitzpatrick: Learning how to apply the gospel to my daily situations has been transformative. I’ll need this framework for island life too!

- Child Proof: Parenting by Faith Not Formula by Julie Lowe

- Becoming a Gospel Mom: A Workbook for Intentional Growth and Reflection by Emily A. Jensen and Laura Wifler

- Waiting Is Not Easy!, an Elephant and Piggie book by Mo Willems

- Even Here: Finding God in Mental and Emotional Suffering, a true gift to the church by Ben Willey.

- Forgive: Why Should I and How Can I?: my favorite book by Tim Keller.

- The Celebration Hymnal

- Evidence Not Seen: A Woman’s Miraculous Faith in the Jungles of World War II by Darlene Deibler Rose: Here’s a story of how God met a woman during a lengthy time of incredible suffering. I heard the “banana story” as a kid in Sunday school and was thrilled to stumble across it in this book a few months ago!

- Joy: 100 Poems edited by Christian Wiman: I’ve recently learned how poetry helps me notice and hold on to those small, transcendent moments of joy in daily life.

- Little Women by Louisa May Alcott: This book is like wrapping yourself in a warm blanket. The whole idea that each of us has strengths and weaknesses and the capacity for growth is a timeless message. (I thought my covetousness was due to social media, but nope, this is a human struggle that has existed long before the internet.)

- The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese: This epic transported me to a community in a different time and place with brilliantly developed characters. I want to read it again!

Thank you, Kristen!

Readers, what do y’all think? If you were stranded on a desert island for the rest of your life and could have only one playlist or one bookshelf with you, what songs or books would you choose?

- For a Desert Island Playlist, send me a list between 5 and 12 songs, excluding hymns and worship songs. (We’ll cover those later.)

- For a Desert Island Bookshelf, send me a list of up to 12 books, along with a photo of all the books together.

Send your list (or both lists) to questions@russellmoore.com, and include as much or as little explanation of your choices as you would like, along with the city and state from which you’re writing.

Quote of the Moment

“The two hemispheres of my mind were in the sharpest contrast. On the one side a many-islanded sea of poetry and myth; on the other a glib and shallow ‘rationalism.’ Nearly all that I loved I believed to be imaginary; nearly all that I believed to be real I thought grim and meaningless.”

—C. S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy

Currently Reading (or Re-Reading)

- Graham Tomlin, Blaise Pascal: The Man Who Made the Modern World (Hodder & Stoughton)

- John Behr, In Accordance with the Scriptures: The Shape of Christian Theology (Cascade)

- Rebecca West, Radio Treason: The Trials of Lord Haw-Haw, the British Voice of Nazi Germany (McNally Editions)

- David Rosenberg, ed., Congregation: Contemporary Writers Read the Jewish Bible (Harcourt Brace)

- Charles Williams, All Hallows’ Eve (Regent College Publishing)

Join Us at Christianity Today

Founded by Billy Graham, Christianity Today is on a mission to lift up the sages and storytellers of the global church for the sake of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Subscribe now to get exclusive print and digital content, along with seasonal devotionals, special issues, and access to the full archives. Plus, you’ll be supporting this weekly conversation we have together. Or, you could give a membership to a friend, a pastor, a church member, someone you mentor, or a curious non-Christian neighbor. You can also make a tax-deductible gift that expands CT’s important voice and influence in the world.

Ask a Question or Say Hello

The Russell Moore Show podcast includes a section where we grapple with the questions you might have about life, the gospel, relationships, work, the church, spirituality, the future, a moral dilemma you’re facing, or whatever. You can send your questions to questions@russellmoore.com. I’ll never use your name—unless you tell me to—and will come up with a groan-inducing pun of a pseudonym for you.

And, of course, I would love to hear from you about anything. Send me an email at questions@russellmoore.com if you have any questions or comments about this newsletter, if there are other things you would like to see discussed here, or if you would just like to say hello.

If you have a friend who might like this, please forward it, and if you’ve gotten this from a friend, please subscribe!

Russell Moore

Editor in Chief, Christianity Today

P.S. You can support the continued work of Christianity Today and the Public Theology Project by subscribing to CT magazine.

Moore to the Point

Join Russell Moore in thinking through the important questions of the day, along with book and music recommendations he has found formative.

Delivered free via email to subscribers weekly. Sign up for this newsletter.

You are currently subscribed as no email found. Sign up to more newsletters like this. Manage your email preferences or unsubscribe.

Christianity Today is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

“Christianity Today” and “CT” are the registered trademarks of Christianity Today International.

Copyright ©2025 Christianity Today, PO Box 788, Wheaton, IL 60187-0788

All rights reserved.