Hello, fellow wayfarers … What the new Superman movie ought to show each of us about our own personal kryptonite … Why evangelicals don’t seem to care about African AIDS victims … How to reclaim your attention from your devices … Where you can find help thinking through the AI era … A Louisville slugger of a Desert Island Bookshelf … This is this week’s Moore to the Point.

Why Superman Matters

As I’m writing this, I am preparing to go with my sons to see a one-day-early screening of the new Superman film by James Gunn. I can hardly wait.

No doubt that moviegoers and my fellow Superman fans will argue about the movie—its continuity in the tradition of the classic 1978 Superman with Christopher Reeve, and so forth.

One debate trope I hope does not return, though, is the well-worn argument that “Superman is boring because he’s too powerful and can’t be hurt.” Here’s why that matters.

I do not write this as a neutral observer but as a fan of the character—and of the larger DC universe—since before I was even able to read. The stories from Smallville and Metropolis (and Gotham and Central City and Paradise Island) populated the Fortress of Solitude that was my childhood imagination in ways that, looking back, I think pointed me onward to the writings of Lewis and Tolkien and beyond.

But why did I and millions of others over the past 80 years want to put that red blanket over our shoulders and pretend to fly?

Author Grant Morrison (himself a prolific writer of comic books and graphic novels) has argued that Superman persists because he represents hope and power; he is the pop-culture equivalent of a sun god.

Some psychologists would say that Superman appeals to us because of his power. We long for the grandiosity inherent in the ability to fly, outpace bullets, see through walls, or, as on the cover of that first Action Comics, lift a car over our heads.

Some would say that children especially identify with the phenomenon of the secret identity: “I might seem to be bumbling, bespectacled Clark Kent, but if you could just see me in my Kryptonian battle armor …”

The idea of Superman as the idealization of strength and power would make sense. His name, after all, comes from Friedrich Nietzsche and his idea of the Übermensch in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. But if Nietzschean power were what we longed for, then there would be other characters more powerful than Superman to stand in for hope. The atomic symbol of Watchmen’s Doctor Manhattan, for example, would be far more appropriate than the S-shaped logo of the House of El.

No, what we love about Superman is not his power so much as his vulnerability. In this, playwright David Mamet was right when he wrote in the 1980s that the real draw of Superman is not flight or x-ray vision but kryptonite. “Kryptonite is all that remains of his childhood home,” Mamet wrote. “It is the remnants of that destroyed childhood home, and the fear of those remnants, which rule Superman’s life.” He continues,

Far from being invulnerable, Superman is the most vulnerable of beings, because his childhood home was destroyed. He can never reintegrate himself by returning to that home—it is gone. It is gone and he is living among aliens to whom he cannot even reveal his rightful name.

The Superman mythos, he concludes, is a fable not of strength but of a “cry for help.”

Mamet is partly right. An inexpressibly powerful alien force would not be as beloved, because it wouldn’t seem to ring true in our own lives. Kryptonite is the symbol of brokenness.

More than the literal kryptonite, though, is the metaphorical kryptonite in the background. Superman wears the uniform of a lineage far away and lost forever. Beyond that, he has learned to lose those who welcomed him into the human family—the Kents.

Superman may be the Man of Tomorrow, but he can be hurt; he can even be killed. And even worse, he can lose those he loves. We can identify with this. We don’t all come from Krypton, but we all have kryptonite.

This brokenness, however, leads to purpose and mission. In the Geoff Johns era of Action Comics (one of the best, in my opinion), Jonathan Kent tells his son, “Your greatest power isn’t being able to fly or see through walls. It’s knowing what the right thing to do is.” That’s consistently true of the character over the past 80 years. That’s one of the reasons the incarnation of Superman as a husband and a father is especially inspiring, as he tries to do his best to balance family and work.

One of my favorite Superman scenes is from Scott Snyder and Jorge Jiménez in their run on the Justice League comics series of June 2019. Superman, drained off-world of his power, reignites out of sheer force of will. The scene—expertly drawn by Jiménez—shows Superman charging through the sky between the reflections of his father, Jonathan Kent, and his son, also named Jonathan Kent. The scene sums up a legacy and a future that gives Clark Kent his power and also makes him able to be hurt.

This sense of mission, and the ethical framework undergirding it, is activated not by a yellow sun but by patient parenting. It didn’t come from Krypton but from Kansas. Superman may carry out his adventures with the powers of Kal-El, but all the while, he’s really Clark Kent. Those principles point him back to the joy and hurt of a love that can die but is as strong as death (Song 8:6)—stronger, even.

That’s why the other “boring” charge against Superman—that he’s too much of a Boy Scout—doesn’t work either. In a 2021 piece in Entertainment Weekly, journalist Darren Franich explores why the concept of an “Evil Superman” keeps reappearing, whether it’s the twisted Ultraman version of Earth-Three, the red kryptonite storyline of the Smallville television series of a quarter century ago, or the diabolical Homelander of Amazon Prime’s The Boys. Franich writes:

The arrival of an Evil Superman is meant to connote adulthood and maturity—the kind of stuff you could never ever get away with in kid stuff. Mature content isn’t the same as maturity, though, and it’s notable how often an Evil Superman is also a character without a supporting cast, a proper job, or even any motivation beyond pure lizard-brain violence.

How often is that version of “maturity”—of the Evil Superman kind—seen right now in this era, both in the church and in the world? Hedonism is maturity. Rage is passion. Propaganda is vision. Cruelty is strength. Intuitively we know this isn’t right, and we have to shut down our consciences to pretend it is.

One of the most striking Superman covers of all time would have to be in the J. Michael Straczynski “Grounded” run of 2010–2011, depicting a little boy wearing a Superman-logo T-shirt as he looks upward. He has a black eye. The story—one of the few in which we see a Superman in his right mind and furious at the same time—depicts the little boy asking Superman, who bears a similar mark of injury, “Does your Dad beat you too?”

No, he didn’t. And that’s why the fury-filled Superman goes to find this abusive father. He knows that this isn’t normal, that it isn’t right.

Much has been made of the religious imagery in the Superman mythos, especially the Old Testament echoes of Moses in the basket. Some have suggested that Superman is a Christ figure, a concept implicit throughout the Superman Returns film and elsewhere.

As a Christian, though, I think we identify with Superman not so much because he is godlike but because he is, underneath it all, so very human. We might be thrilled to see a superhero flying upward in the skies above us, but really, we’re looking past him for Someone else.

We all like to be saved from danger by a real or imagined Superman every once in a while. But Supermen have come and gone. This character has persisted for almost a century. That’s not because we think he can save us, but because we know, deep in our hearts, that a Superman needs a savior too.

Note: This is a revised, expanded, and updated version of “Who Will Save Superman?” published on my website on April 17, 2018, on the 80th anniversary of the creation of the character.

Why Evangelicals Don’t Care About PEPFAR

My friend Peter Wehner has a new piece up at The Atlantic on the odd silence of evangelical pastors and leaders on the destruction of the PEPFAR program, a dismantling that could cost millions of innocent lives.

I am quoted in the piece, as are Amy Grant, Michael Keller, and others. Here is Pete’s sobering conclusion:

Evangelicals in America—for a dozen different reasons—have mostly turned their eyes away from what is happening on the African continent. They have other things to do. They have culture wars to fight.

Jesus knew such people in his time. They were religious figures who, when they saw that wounded traveler on the road to Jericho, passed to the other side.

Read the whole thing here.

How to Save Your Attention in a Digital Age

Ever since reading his article “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” way back in what seems a whole other era—2008—I’ve wanted to talk to Nicholas Carr. Now I have, and he was as provocative and fascinating as I expected him to be.

We all talk about “doomscrolling” and “brain rot.” These concepts have become so familiar to us and part of our everyday monotony that they have become jokes.

But Nicholas Carr isn’t laughing.

Carr’s work in tech journalism has given him a front-row seat to watch the shift of culture around technology over the last decade, and his recent book, Superbloom: How Technologies of Connection Tear Us Apart, explores his observations. The news isn’t great. It seems like online platforms and algorithms know us better than our churches, families, or friends do, especially when the product we glanced at for a fleeting moment now fills our timelines and social media feeds.

But we already knew that, right?

Still, we face obstacles to capture our own conscious minds. In our conversation, Carr lays out a mandate for a cultural revolution to reclaim the human experience from the clutches of technology. He explains that what’s at stake is the understanding of community, which finds its roots in the ability to focus to form empathy for others.

Our conversation shines a light on the profound need for deeper connections and the importance of attention in fostering meaningful relationships. We also talk about the mirage of screens as socialization, an AI priest (whose story doesn’t end well), positive outcomes from machines and technology, and how separating from technology might feel an awful lot like excommunication.

Along the way, I quote from Wendell Berry’s poem “The Vacation,” which will linger in your mind after you read it on every vacation you ever take.

If you’re needing to be emboldened to cut your screen time or make a change in the way you use technology for your sake and the sake of future generations, this conversation might be the thing you need.

Listen to it here.

How to Save Your Attention in a Digital Age

The interview with Carr is in podcast form, with another version in the new July/August issue of Christianity Today, which is themed around questions of artificial intelligence and what the future means for Christians.

The issue covers everything from dating apps to transhumanism to how reading Ecclesiastes can make you happier. This might be my favorite issue yet. And the cover art by the legendary John Hendrix is mind-blowingly amazing. Check it out.

And, while you’re thumbing through those pages, our team has cooked up a midyear gift for new subscribers:

Midyear Special (July 9–18)

• Save $10 on a two-year Digital + Print subscription

• Six recent print issues—free. (That’s a $70 bookshelf-worthy bonus.)

The fine print: New US subscribers only; international readers are automatically steered to $20 off a two-year digital plan. Upgrades, renewals, and gifts aren’t included—this one’s just for the newcomers.

If you’ve been meaning to jump in, now’s the moment.

Desert island bookshelf

Every other week, I share a list of books that one of you says you’d want to have on hand if you were stranded on a deserted island. This week’s submission comes from reader Jonathon Crump from my old stomping grounds, Louisville, Kentucky. Jonathon and I have very similar tastes in books, so I would like to sit down with him one day to talk about them.

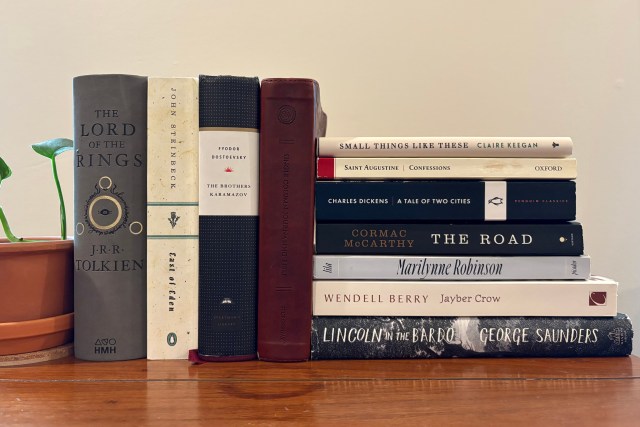

Here’s his list:

- The Bible. Obviously. ESV, single column.

- Lila by Marilynne Robinson: My favorite of the Gilead series. Lila’s slow and awkward entrance into civilization and romance, her fascination with Ezekiel—it’s just wonderful.

- Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan: I’ll read this every December I’m on the island to give me a sense of time and liturgical rhythm. I imagine reading about snow on a desert island is good for the soul.

- East of Eden by John Steinbeck: One of the best American novels. A long book that feels like half of its length with plenty of believable characters, mystery, and themes to chew on.

- The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien (edition with all three books in one): I’ve only read through the trilogy once. With all the time on the desert island, I’ll be able to read it multiple times, I’m sure!

- Shakespeare’s Sonnets by William Shakespeare: I’ll want poetry on the island. I can savor each sonnet and work my way through Shakespeare’s sonnet sequence multiple times over.

- Confessions by Saint Augustine, transl. Henry Chadwick: Chadwick’s classic translation. This book keeps me sane.

- The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky: This is the most demanding book I’ve ever read. Some parts were glorious, other parts were utterly opaque to me. This is obviously a book that rewards and encourages a reread. On the island, I’ll have plenty of time to give this book the reread(s) it deserves.

- Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders: One of my favorite books that has come out during my lifetime. This book has so many characters and voices that I know it will keep me entertained for years and years.

- A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens: Never read it! It seems big and intricate and seems like it will be rewarding to read and reread.

- The Road by Cormac McCarthy: My favorite McCarthy. Very dark but the love between the father and son gives me so much hope.

- Jayber Crow by Wendell Berry: This book has so many scenes, characters, and lines worth mulling over. Berry’s writing has always been dense but rewarding to me. Like reading an encyclopedia written by a poet. Jayber feels like a friend by the end of this novel. When I reread this on the desert island, I want to give as much attention to the other characters.

Thank you, Jonathon!

Readers, what do y’all think? If you were stranded on a desert island for the rest of your life and could have only one playlist or one bookshelf with you, what songs or books would you choose?

- For a Desert Island Playlist, send me a list between 5 and 12 songs, excluding hymns and worship songs. (We’ll cover those later.)

- For a Desert Island Bookshelf, send me a list of up to 12 books, along with a photo of all the books together.

Send your list (or both lists) to questions@russellmoore.com, and include as much or as little explanation of your choices as you would like, along with the city and state from which you’re writing.

Quote of the Moment

“We assume that only children are spoiled and pampered; but they also are made to share adult perspectives. Possibly the household that nurtured me was a distracted and needy one—in severe Depression-shock—which asked me to grow up too early; at some point I acquired an almost unnatural willingness to make allowances for other people, a kind of ready comprehension and forgiveness that amounts to disdain, a good temper won by an inner remove. If I’m nice and good, you’ll leave me alone to read my comic books.”

—John Updike, Self-Consciousness: Memoirs

Currently Reading (or Re-Reading)

- Christopher Hays, ed., The Cambridge Companion to the Book of Isaiah (Cambridge University Press)

- Adam Plunkett, Love and Need: The Life of Robert Frost’s Poetry (Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

- Richard Holmes, Coleridge: Darker Reflections (HarperCollins)

- P. T. Forsyth, Positive Preaching and the Modern Mind (Paternoster)

- James Wood, The Broken Estate: Essays on Literature and Belief (Picador)

Join Us at Christianity Today

Founded by Billy Graham, Christianity Today is on a mission to lift up the sages and storytellers of the global church for the sake of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Subscribe now to get exclusive print and digital content, along with seasonal devotionals, special issues, and access to the full archives. Plus, you’ll be supporting this weekly conversation we have together. Or, you could give a membership to a friend, a pastor, a church member, someone you mentor, or a curious non-Christian neighbor. You can also make a tax-deductible gift that expands CT’s important voice and influence in the world.

Ask a Question or Say Hello

The Russell Moore Show podcast includes a section where we grapple with the questions you might have about life, the gospel, relationships, work, the church, spirituality, the future, a moral dilemma you’re facing, or whatever. You can send your questions to questions@russellmoore.com. I’ll never use your name—unless you tell me to—and will come up with a groan-inducing pun of a pseudonym for you.

And, of course, I would love to hear from you about anything. Send me an email at questions@russellmoore.com if you have any questions or comments about this newsletter, if there are other things you would like to see discussed here, or if you would just like to say hello.

If you have a friend who might like this, please forward it, and if you’ve gotten this from a friend, please subscribe!

Russell Moore

Editor in Chief, Christianity Today

P.S. You can support the continued work of Christianity Today and the Public Theology Project by subscribing to CT magazine.

Moore to the Point

Join Russell Moore in thinking through the important questions of the day, along with book and music recommendations he has found formative.

Delivered free via email to subscribers weekly. Sign up for this newsletter.

You are currently subscribed as no email found. Sign up to more newsletters like this. Manage your email preferences or unsubscribe.

Christianity Today is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

“Christianity Today” and “CT” are the registered trademarks of Christianity Today International.

Copyright ©2025 Christianity Today, PO Box 788, Wheaton, IL 60187-0788

All rights reserved.