Hello, fellow wayfarers … Why rethinking the way we talk about humanity as the image of God is necessary as we enter the age of AI … What a proto-punk rock song about Jesus taught me this week … Where you can get a little post–Labor Day surprise … What Philip Yancey would say differently—and what he would say the same—about disappointment with God … This is this week’s Moore to the Point.

To Prepare for an Era of AI, We Need to Pay Attention to Our Image of God

I once took an artificially intelligent cyborg to vacation Bible school.

Nearly 20 years ago now, students in my Christian ethics class at Southern Seminary confronted the question of artificial intelligence in their final exam. I asked them to imagine their future great-grandson, “Joshua,” as a minister within what used to be called the Southern Baptist Convention (but is now the “Galactic Immersionist Federation”).

In this imagined future, Pastor Joshua sits across the desk from Aiden, a little boy going to the church’s summer outreach program. Aiden wants to know how he can become a Christian. He wants to repent of his sins, put his faith in Jesus, and go to heaven when he dies.

The catch: Aiden is manufactured, a Frankenstein’s creation of cloned human body parts with a generative AI mind. The question my students faced was “What would you advise Pastor Joshua to do?” Should he walk Aiden through the answer to the ancient query “What must I do to be saved?” (Acts 16:30). Does the “whosoever” in John 3:16 apply to him—or, should I say, to it?

The point of that final exam was to dislodge students from their tendency to treat ethical dilemmas like a world-view concordance of right answers to premade questions. I wanted to see not so much their answers as how they arrived at their answers—how they integrated the Bible and the gospel into a situation for which they probably didn’t have preexisting slogans.

Today, those students are still far from having great-grandchildren, yet here we all are. We’re on the cusp of what some are calling an “axial decade,” in which advances in artificial intelligence may spur on the contemporary equivalent of the Axial Age (when the emergence of literacy transformed the way human beings exist in the world).

Pastor Joshua might not be born yet, but Aiden is here. And the church is not ready. Indeed, to talk seriously about AI is to risk causing the same reaction that many of my students had to their final—categorizing it as futuristic science fiction. But the root of our unreadiness is not that we don’t adequately understand what a chatbot is. It’s that we don’t sufficiently understand what a human being is.

The crisis of our age is a radical reducing of human life to a flow of data and information, so much so that some tech pioneers suggest eternal life can be achieved by uploading our minds to a digital cloud. Douglas Rushkoff describes this mindset as “the belief that we can code our way out of this mess,” presuming that in a world of code, “anything that isn’t yet code can eventually be converted to a digital format as easily as a vinyl record can be translated to a streaming file.”

Christians, of course, have a distinctive view of the human person as imago Dei—made in the image and likeness of God (Gen. 1:27). The problem is that modern Christians often unintentionally speak of this distinctiveness in terms just as machinelike as those used by the world around us.

We try to identify what “part” of us bears the image. We are morally accountable, we say, unlike other animals—and that’s true, but the Bible tells us there are other morally accountable beings in the universe (1 Cor. 6:3). Or we point to our ability for relationship—and that’s true also, but what does that say when people fall in love with their chatbots?

Perhaps most problematically, we speak of the imago Dei as our rationality, our ability to think and to reason. But intelligence has never been exclusive to human beings. The Serpent of Eden is described as “crafty” or “cunning” (Gen. 3:1; 2 Cor. 11:3), and the apostle Paul spoke of the “schemes” of the Devil (Eph. 6:11, ESV throughout).

After Genesis, though, the Bible doesn’t further define the concept of the image of God until the New Testament. Even then, it defines that image not as a what or a how but a who.

Jesus, Paul wrote, is “the image of the invisible God” (Col. 1:15). The Incarnation means that Jesus joined us in flesh and blood, in our suffering and creatureliness, in order to free us from our captivity to the power of death (Heb. 2:14–15). All creation is meant, somehow, to recognize humanity as signifying the reign of God (Rom. 8:19). And in the flesh-and-blood person of Jesus, it does. Even the molecular structures of fish and bread obey him and multiply. In strikingly personal terms, Jesus says, “Peace! Be still!” to the wind and waves, and they respond (Mark 4:39).

Paul speaks of creation as revealing the “invisible attributes” of God (Rom. 1:20) in ways that mirror the concept of the image of God. This is not the potential to trace philosophical arguments from the order of the world back to God; the Bible says this revelation to humanity is “plain to them, because God has shown it to them” (v. 19). Something in our being is meant to resonate with the awe and mystery of the world, triggering us to recognize something—someone—behind the veil of what we

can see.

The church in the AI age must recognize that to be human is not about “stuff” that can be weighed or quantified. We must understand that there’s a mystery to life that cannot be uploaded or downloaded or manipulated by technique. Simply recognizing this in an age of smart machines is a good start.

The world has always asked what the meaning of human life is. It is about to start asking what it means to be human at all. That’s a final examination question for us all.

A robot can give an answer, but that’s not enough. We should point to a Person. And in an age of artificial intelligence, as always, that will be strange enough to save.

Note: This is an adaptation of my column in the July/August issue of Christianity Today.

A Song About Jesus That Changed My Week

On Labor Day, I was walking some trails with my friend Ian Cron—whom many of you know for his writings on psychology, personality, religion, addiction, and other topics—when he mentioned a song by Lou Reed, called simply “Jesus.” I had never heard of this because I am, as you know, much more George Jones than The Velvet Underground. (My dogs were/are named Waylon and Willie, not … well, I don’t know enough people in that genre to even name them for comparison’s sake.)

Ian got my attention when he mentioned that Glen Campbell had covered the song—so I listened to that version. The simple line that’s repeated over and over again in this song really struck me: “Jesus, help me find my proper place.” It seems that is a version of a prayer often articulated in Scripture, like when King David sang, “You have set my feet in a broad place” (Ps. 31:8).

As I listened to the song, I thought about all the people I’ve talked to this week who were wrestling with that very prayer. One person was trying to decide on his life’s calling. Another was seeking to know whether a potential spouse was the right one for her. Yet another was scared of dying. It’s all a version of “Jesus, help me find my proper place.”

And that’s a prayer that is, at best, only partially answered in this life. The one who finds a home must lose it, after all (Heb. 11:13–16; 13:12–14). Still, the prayer is partially answered. One of my favorite passages in recent years is from Isaiah 30:19–21:

He will surely be gracious to you at the sound of your cry. As soon as he hears it, he answers you. And though the Lord give you the bread of adversity and the water of affliction, yet your Teacher will not hide himself anymore, but your eyes shall see your Teacher. And your ears shall hear a word behind you, saying, “This is the way, walk in it,” when you turn to the right or when you turn to the left.

That seems to be a kind of answer to the plea that Lou Reed was making in that song.

By the way, Glenn Campbell also did a cover of Green Day’s “Good Riddance (Time of Your Life)” that is better than the original and transforms it just by the way he sings the meaning of it, kind of like what Johnny Cash did to Nine Inch Nails’s “Hurt.”

Post–Labor Day Surprise

I don’t normally put my column for the magazine here, but I decided to this week because CT is offering a special Labor Day–week sale on subscriptions. My column is the least interesting article in every issue, so if you like it, you will like the rest more.

The sale is for 25 percent off both print and digital subscriptions and gives access to almost 70 years’ worth of good stuff online. Here’s the catch: that ends tomorrow, September 4, so go ahead and do it now that you’re thinking about it!

You can subscribe here.

Philip Yancey Is Not Disappointed with God

When I was a high-schooler, I would read Philip Yancey’s columns and quickly moved on to reading his books as well. At a time when I was confused about what was real, I learned to trust Yancey’s authentic, literate, and joy-filled vibe. (I wouldn’t have called it that back then, but you know what I mean.)

You might have read his best-selling books, such as What’s So Amazing About Grace?, Where Is God When It Hurts?, and The Jesus I Never Knew.

This week he comes back on the show to talk about suffering, lament, and pain. I wanted to check in with him to see if the very real suffering he’s experienced in recent years—dealing with cancer and Parkinson’s disease—has changed anything about the way he once talked about disappointment with God and the problem of pain.

Along the way, we talk about what the Book of Job says—and doesn’t say—about suffering, and why Jesus didn’t “solve” pain during his earthly ministry. Plus, he talks about how you know if you’re offering people clichés and fake reassurance or real comfort.

You can listen to it here.

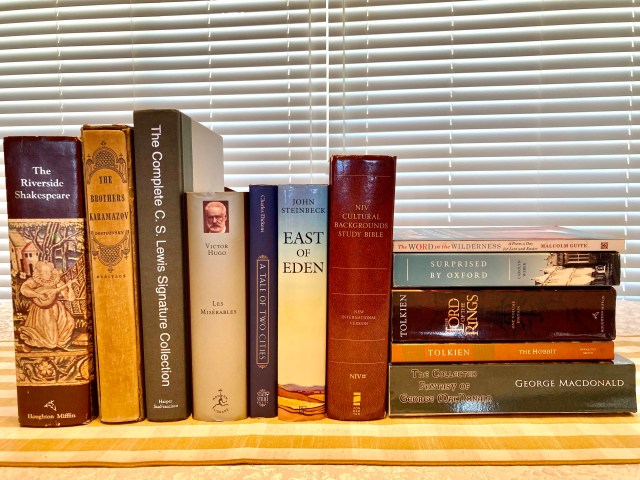

Desert island bookshelf

Every other week, I share a list of books that one of you says you’d want to have on hand if you were stranded on a deserted island. This week’s submission comes from reader Cheryl Arnold, a teacher in Ocala, Florida. Cheryl says that she plans to visit us here at Immanuel Church when she comes to Nashville for a concert later this fall, so I will look forward to meeting her in person.

Here’s her shelf:

- Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible (NIV) ed. by Craig S. Keener and John H. Walton: I have quite a few Bibles in different versions, but since I will not have other commentaries with me, this one provides helpful insights into the culture and customs of ancient times.

- The Riverside Shakespeare ed. by G. Blakemore Evans: I loved the Shakespeare elective courses I took in both high school and college, and this collection of his complete works was my college textbook. It includes his comedies, histories, tragedies, romances, and poems, along with annotations and commentary. There is a play or poem to suit any mood.

- The Collected Fantasy of George MacDonald: I have the complete works of George MacDonald on my Kindle—18,755 pages in all. My favorite works of his are his fantasies, so I would bring this collection, which includes Phantastes, The Light Princess, The Princess and the Goblin, The Princess and Curdie, Lilith, and more.

- The Complete C. S. Lewis Signature Classics: While tempted to bring Till We Have Faces or a volume or two from The Chronicles of Narnia, I chose this anthology, which includes Mere Christianity, The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, The Problem of Pain, Miracles, A Grief Observed, and The Abolition of Man. This way, I could read some nonfiction and also pair Phantastes with The Great Divorce, since Phantastes and MacDonald are important in that story.

- The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien: This volume contains all three books of the trilogy. I listened to The Lord of the Rings on an audiobook voiced and sung by a royal Shakespearean actor, so on the desert island I could read and savor the print version.

- The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien: If I am going to bring The Lord of the Rings, then I need to bring The Hobbit too.

- Les Misérables by Victor Hugo: I have seen the musical several times, but the book is still in my “someday” pile. I would love to finally read it.

- East of Eden by John Steinbeck: I read this as a young adult, and I would like to revisit this classic and its biblical themes now that several decades have passed.

- A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens: I loved this book when I read it in a high school British lit class, and it is another classic with biblical themes that I would like to revisit.

- The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoyevsky: This is another book I read while in high school. I skimmed through parts of it and did not have enough life experience to fully appreciate the depth and themes of this story, although parts of it have stayed with me over the years. I have seen it referenced many times this past year, and each time I am reminded that I want to revisit this book and dive into its richness now that I have more life experience.

- Surprised by Oxford by Carolyn Weber: I love reading memoirs, and this is one of my favorites. Weber’s story of coming to faith at Oxford has some parallels to that of C. S. Lewis, and it is also a love letter to Romantic literature and poetry, with many literary excerpts sprinkled throughout the book. This memoir reignited my interest in both C. S. Lewis and poetry.

- The Word in the Wilderness by Malcolm Guite: After reading Surprised by Oxford, I began reading more poetry and building a collection of poetry books. It was difficult to choose just one volume to take to the desert island, but I selected this one because it focuses on the Cross. It includes some beloved classics by Herbert, Donne, Dante, Lewis, and Hopkins, as well as some of Guite’s own sonnets, along with his devotional commentary on all of the poems.

Thank you, Cheryl!

Readers, what do y’all think? If you were stranded on a desert island for the rest of your life and could have only one playlist or one bookshelf with you, what songs or books would you choose?

- For a Desert Island Playlist, send me a list between 5 and 12 songs, excluding hymns and worship songs. (We’ll cover those later.)

- For a Desert Island Bookshelf, send me a list of up to 12 books, along with a photo of all the books together.

Send your list (or both lists) to questions@russellmoore.com, and include as much or as little explanation of your choices as you would like, along with the city and state from which you’re writing.

Quote of the Moment

“But it would be very dangerous to have no worries—or rather no occasions of worry. I have been feeling that very much lately: that cheerful insecurity is what our Lord asks of us.”

—C. S. Lewis in Yours, Jack

Currently Reading (or Re-Reading)

- Paul Kingsnorth, Against the Machine: On the Unmaking of Humanity (Thesis)

- Daniel J. Flynn, The Man Who Invented Conservatism: The Unlikely Life of Frank S. Meyer (Encounter)

- Thomas Mann, Mario the Magician and Other Stories, trans. H. T. Lowe-Porter (Minerva)

- George M. Marsden, The Soul of the American University: From Protestant Establishment to Established Nonbelief (Oxford University Press)

Join Us at Christianity Today

Founded by Billy Graham, Christianity Today is on a mission to lift up the sages and storytellers of the global church for the sake of the gospel of Jesus Christ. For a limited time, you can subscribe and get 25 percent off both print and digital subscriptions, along with seasonal devotionals, special issues, and access to the full archives. Plus, you’ll be supporting this weekly conversation we have together. Or, you could give a membership to a friend, a pastor, a church member, someone you mentor, or a curious non-Christian neighbor. You can also make a tax-deductible gift that expands CT’s important voice and influence in the world.

Ask a Question or Say Hello

The Russell Moore Show podcast includes a section where we grapple with the questions you might have about life, the gospel, relationships, work, the church, spirituality, the future, a moral dilemma you’re facing, or whatever. You can send your questions to questions@russellmoore.com. I’ll never use your name—unless you tell me to—and will come up with a groan-inducing pun of a pseudonym for you.

And, of course, I would love to hear from you about anything. Send me an email at questions@russellmoore.com if you have any questions or comments about this newsletter, if there are other things you would like to see discussed here, or if you would just like to say hello.

If you have a friend who might like this, please forward it, and if you’ve gotten this from a friend, please subscribe!

Russell Moore

Editor in Chief, Christianity Today

P.S. You can support the continued work of Christianity Today and the Public Theology Project by subscribing to CT magazine.

Moore to the Point

Join Russell Moore in thinking through the important questions of the day, along with book and music recommendations he has found formative.

Delivered free via email to subscribers weekly. Sign up for this newsletter.

You are currently subscribed as no email found. Sign up to more newsletters like this. Manage your email preferences or unsubscribe.

Christianity Today is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

“Christianity Today” and “CT” are the registered trademarks of Christianity Today International.

Copyright ©2025 Christianity Today, PO Box 788, Wheaton, IL 60187-0788

All rights reserved.