Four biblical perspectives

In an election year, preachers are forced to decide how, and if, they will address the controversial issues raised by campaigns. That is a daunting task, particularly when people within the church differ on how biblical teaching applies politically. Brian Lowery, managing editor of PreachingToday.com, asked four pastors how they approach the task of preaching in a season of heightened political awareness without wandering off course. He discovered four distinctly different views.

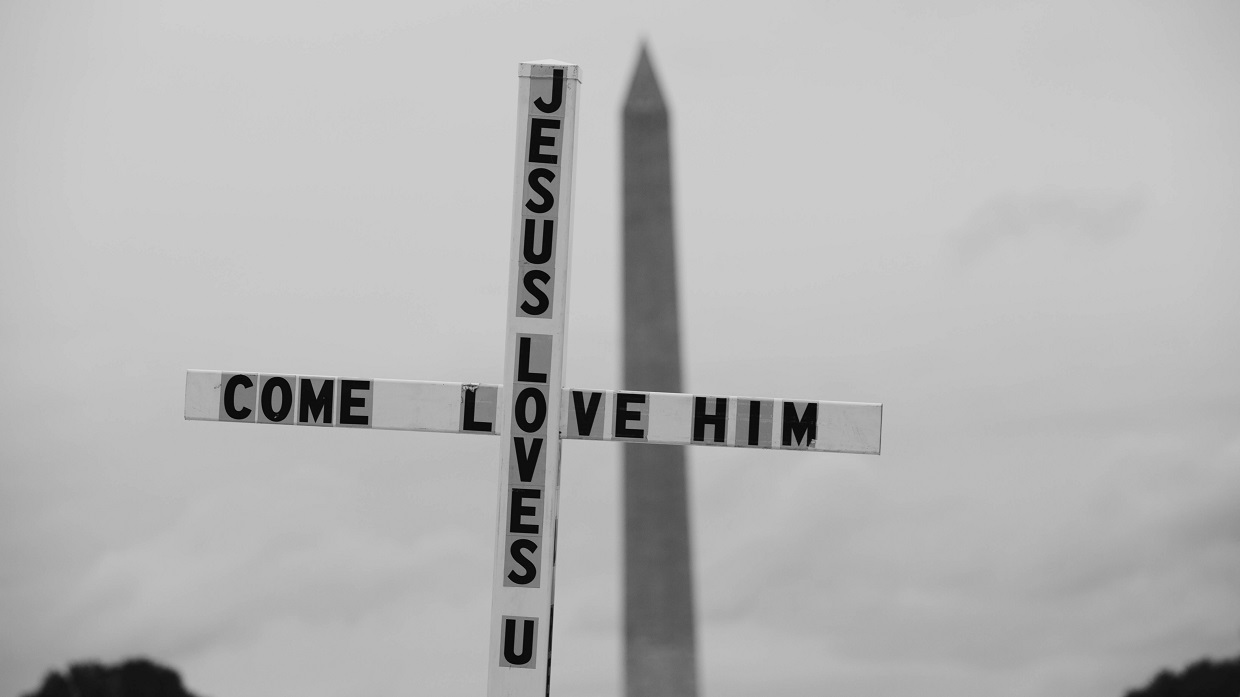

Keep the Gospel Clear and Distinct

Mark Dever pastor of Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington, D.C. and author of Twelve Challenges Churches Face (Crossway, 2008).

Jesus told Pilate that his kingdom is not of this world, so I don't want to confuse my role as a preacher with the role of politicians and government servants. I don't act fundamentally as a counselor in political matters. I expound Scripture and the truth about the gospel, letting the political parties do what they will.

One party may increasingly identify itself with something I think is clearly sinful in Scripture—like same-sex marriage—while the other doesn't support it at all. But I can't allow myself to be duped into believing that either party is acting out of obedience or disobedience to Scripture. While one party may be more consistent with Scripture on one particular issue than on others, both parties operate primarily with secular mindsets.

We must not confuse the gospel with other passing matters. Ours is not a Christian country. We are Christian stewards of the votes the Lord commits to us, but we can't presume that we are creating morality for a nation of regenerate people. As much as we hope to persuade our fellow citizens that it is in their best interest to act in accordance with the morality we see in Scripture, I have no reason to presume in a fallen world that we'll always be able to persuade sinners to live according to what God has revealed of himself.

Preaching is the exposition of the Word of God, not trying to prooftext a particular political issue.

Too many Christians today are trying to improve on the gospel. The gospel is what it is: the Cross of Christ. Christians on both the political right and the left are downplaying the effects of the Fall, and instead buying into a secular myth of progress through market economics or socialism. That is not something a Christian preacher should adopt.

A Christian preacher should be critical of any temptation toward earthly Utopianism. The answer to the world's ills is not even something as good as outlawing abortion. I certainly would like for us to have such laws, but even more, I'd like people not to want to kill unborn babies. There's only so much outward conformity that laws can build into a people who are not in agreement with the heart issues.

It serves us well to understand the difference between the gospel and the implications of the gospel. Too many evangelicals are concerned about the latter at the expense of the former.

I recently had an interesting conversation with a friend who works in the federal government. He said, "I'm around people all day long who work alongside me toward better labor laws or a reduction in Third World debt. They're with me on all the larger social goals, but they're non-Christians. Do I have anything left to say to them?"

My response: "Yes! You have the gospel! They are sinners alienated from God, and they need a Savior."

When preachers start talking about a larger vision for the gospel, their political views often get mingled in. People who disagree with those political views, then, are seen as opponents of the gospel.

Conversely, when I have people who agree with me on political and social ends, I find that since we're cobelligerents in that area, I'm tempted to assume we are cobelligerents for the gospel. But we're often not! We both may want the people in Mauritania to be fed, but my cobelligerent may be an atheist and essentially an enemy of God, while I'm reconciled to God.

The freedom we have to preach the gospel in America is unusual when compared to many of our brothers and sisters around the world (or even in the history of the church). We must take advantage of this rich gift to preach the gospel. Do not make American freedoms or laws or customs or even human rights the center of your message.

Do not be distracted by thinking the reform of drunk driving laws is what your ministry is about. The center of your message is the Cross of Christ.

Clarity in Shades of Gray

Adam Hamilton pastor of United Methodist Church of the Resurrection in Leawood, Kansas, and author of Seeing Gray in a World of Black and White: Thoughts on Religion, Morality, and Politics (Abingdon, 2008).

In theology and politics, the terms "conservative" and "liberal" designate two poles—thesis and antithesis, and the world is often painted in black-and-white terms. The culture wars of the late twentieth century played this out over issues like abortion, human sexuality, welfare reform, immigration, and many other issues.

At the end of the day, this is not a Republican or Democratic issue. This is a kingdom issue.

Too often it was the church and her leaders that fueled the polarization. Instead of acting as peacemakers, loving one's enemies, or being "quick to listen and slow to speak," Christian leaders helped foster deep division in our country.

I found I did not fit on either side of the theological or ideological divide. Instead of the polarizing rhetoric and the black-or-white way the issues are often painted, I sought to find what is best and right and true on both sides, forging a new synthesis of the two poles—what I call a "radical center."

In the radical center, we see that the Sermon on the Mount, the wisdom of Proverbs, the teachings of Paul, and the Epistles by James and John call on Christians to treat one another in ways that break down, rather than erect, dividing walls.

This guides my preaching in many ways. For 2008, I developed a series of sermons to help our congregation approach the presidential election year with grace and humility. I wanted to challenge assumptions about the relationship between faith and politics, inviting people to see the shades of gray in the world we live in and not just stark black or white.

I wanted our church to bring faith and hope and love to the way we practice politics—to approach the divisiveness of the election year with a Christ-like spirit and a commitment to love, which would change political discourse.

The sermon series began the Sunday after the Iowa caucuses and ended the Sunday before Super Tuesday. I knew the news headlines of each week would be about politics, so the importance of the sermon series was reinforced throughout the week.

I did my best to lay out the best motives of people who hold views on both sides of a given issue, even showing the Scriptures both would use as support.

After affirming elements of each side's position, I offered my own scriptural interpretations with humility and grace toward those with whom I disagree. Each week we invited people to comment on the sermons and dialogue about them on our blog. We even posted questions on YouTube, inviting the general public to post their own responses.

When I preach on politically charged topics, I don't think it's my job to spoon-feed people my conclusions. I need to help them understand biblical ethics, including the Old Testament ideas of mishpat, tsedekah, and hesed (respectively translated "justice," "righteousness," and "steadfast love" or "kindness") and how the teachings and parables of Jesus can serve as guiding principles in our political decisions.

Our congregations need to know how to do Christian ethics, how their faith should affect their politics, how to be peacemakers during times of great divisiveness in our country.

As John Wesley wrote more than two hundred years ago: "Would to God that all party names and unscriptural phrases and forms which have divided the Christian world were forgot; that we might all agree to sit down together as humble, loving disciples at the feet of a common Master, to hear his word, to imbibe his Spirit, and to transcribe his life into our own."

Training Agents of Redemption

Joel C. Hunter pastor of Northland Church, a multi-site congregation in central Florida, and author of A New Kind of Conservative(Regal, 2008).

Preaching is the vehicle by which a pastor brings the Word of God to his congregation in order to mature them into the life of Jesus Christ in all the major areas of life. This inevitably includes preaching into the sphere of politics.

When I use the pulpit to deal with political issues, I offer a picture of Christ. When Christ went to the cross, he spoke redemption not only into the lives of individuals but also to the structures of society. I try to offer the general theological components a person needs to address that issue. I want to teach people how to pray about issues in light of Scripture. Whether the issue is poverty or sexuality in culture, I want my listeners to ask two questions: How can Christ redeem this? How can we be agents alongside him?

What I don't do is offer a list of pros and cons on a given issue. I don't believe the pulpit is a place for the typical talk show model where you set up the opposing argument in your terms, so you can knock it down. In fact, I encourage my people not to listen to too much talk radio, because it has a tendency to make us combative rather than constructive. We belong to a sound-byte generation that plays on human emotion and our gullibility to believe there's a simple answer to everything.

Significant problems do not come with easy answers. We have to take an intellectually comprehensive approach. Preachers mustn't drum up a passion that's not going to result in spiritual maturity. We need to define what we want to accomplish rather than what we're against.

Much of evangelical politics has gotten stuck in a petty "middle-school mentality" where we define ourselves by who we hate and what clique we belong to. The preacher's goal is to bring people to spiritual maturity, so we have to be clear about what makes for constructive, redemptive behavior in politics.

Practically speaking, this means that most of what we do at Northland concerning political issues is done in sidebar events that deal with compassion issues or "loving your neighbor" issues.

People interested in learning about, or even debating, a particular issue can come to these settings so we don't get distracted in our larger worship gatherings. Our main purpose for preaching in the larger worship gatherings is the exposition of the Word of God, not trying to prooftext a particular political issue.

If we want to talk about an issue, we do a special event so people can know they're walking into a lively discussion about what they can do on an individual or corporate basis for purposes of influencing public policy. In recent years we've hosted special gatherings on creation care, working with the poor, and issues related to the AIDS epidemic.

Periodically an issue comes along that you have to address in the larger worship settings. If you don't address, or at least acknowledge, what's on people's minds, it's actually a distraction. They're not going to be able to listen to you if you don't seem to care about real events in the real world. The events of 9/11 pushed many of us to address issues like the just war theory and the larger Christian context for conflict.

The issue of immigration is on people's minds, and if you don't say anything about that, you can't help your people keep their rhetoric respectful. I've been working with Hispanic leaders in town to dialogue about comprehensive ways for Northland to approach the issue. And this year, if you say nothing about issues in the upcoming election, you indicate that you're hiding in some sort of enclave.

Despite my effort at avoiding naming candidates and parties and steering clear of the polarizing language of left/right, Democrat/Republican, or conservative/liberal, people will come out of our worship services or sidebar events and say, "I think he's liberal." Others will disagree and say, "No—I think he's conservative!"

I've learned that whenever I address anything political, my sermon becomes a sort of Rorschach test for where people land politically. I can only do my best to intentionally say, "Fix your eyes on Jesus."

Preach Prophetically

Efrem Smith is pastor of The Sanctuary Covenant Church in Minneapolis, and author of The Hip-Hop Church: Connecting With the Movement Shaping Our Culture (IVP, 2006).

Raised in the African-American church tradition, I've always felt that the preacher is primarily a prophetic voice in the public square. If the church did not preach prophetically—if from the pulpit people weren't encouraged to get involved in the political process—we might still have slavery and Jim Crow segregation. History shows that a disconnection between the pulpit and politics would have been detrimental to African-Americans and other non-European Americans.

I believe the preacher is charged with creating bridges between society and the kingdom of God by elevating a fully-embodied, holistic gospel.

We preach a gospel of personal salvation in Christ, but we also lift up a gospel that takes on issues that transform a person's life. We can be holistic just like Jesus. Jesus fed people. He healed people. He spoke about women, children, and those who were imprisoned. Many of these same kingdom issues are being addressed in today's public policy, so I help my congregation find the intersection between the kingdom issue and public policy. The problem is that many kingdom issues have been politicized, so that even when you preach on a biblical issue, people will criticize you for being political.

People can't tell the difference between a conservative evangelical message and Rush Limbaugh, or a mainline Protestant message and Howard Dean. Because of the media, any news item related to major social issues—education, housing foreclosures, healthcare, or youth violence—is politicized within 24 hours.

By the time I get up to preach about it on Sunday, it's been spun and polarized a hundred times over. On Easter Sunday, I decided to address the controversy surrounding Jeremiah Wright by sharing the three theological streams of the Black church: the liberation stream, the reconciliation stream, and the prosperity stream. I wanted the congregation to wrestle through the theological issues so they could have a biblically based, healthy conversation about Rev. Wright.

But the issue had become so politicized by the media, that a small group of people I minister to was convinced I was simply trying to find a way to support Barack Obama.

Finding that bridge between the kingdom and the public square is getting harder because of today's controversy-fueled media, but we're charged with speaking a prophetic word nonetheless. Sometimes I've been able to do this well, and sometimes I've had to clean up after myself. One of the most important things I can do is simply let the issues emerge from Scripture. Don't push these issues into the text; stay within biblical boundaries.

Expository preaching will eventually lead you through the hot topics, and people will see that you desire to preach God's agenda and not prop up some political platform.

When you are preaching through the Gospel of Matthew and you encounter the healing of the woman with an issue of blood in chapter 9, let that text lead your congregation into issues of healing and prevailing attitudes toward the sick, and what we learn of God in this episode.

Does this have application to issues of health, disease, and public policy? Certainly. But when you address the issues, it's important to say, "At the end of the day, this is not a Republican or Democratic issue. This is a kingdom issue."

Once the kingdom issue is established, you can lovingly challenge your congregation to look at their responsibility. I focus my preaching on local political issues, because it offers my congregation immediate action steps to actually do something about an issue.

When six public schools in our surrounding community were closed in the last year and a half, I preached about it. Would Jesus care about how the school closings were affecting our ability to educate our children? I think there's biblical evidence to say he would, so I elevated a few kingdom principles that speak to the matter. Then I shared some action steps we could do as a church community to put our faith into action. As a result our church developed an after school program to tutor kids.

Don't just talk about the church's responsibility, though. Preaching prophetically means you need to challenge the people concerning the government's responsibility as well. When preaching about healthcare, help them see the government's role, if any.

God calls on his people to challenge political leaders. Pharaoh was a political leader, wasn't he? Jesus had conversations with Pilate and Herod. The critical difference is that both Moses and Jesus weren't running for office. They weren't trying to attain power in a political party. They were playing a more prophetic, kingdom-oriented role. Churches may be non-profit, but they dare not be non-prophet.

Copyright © 2008 by the author or Christianity Today/Leadership Journal.Click here for reprint information on Leadership Journal.