When I (Carey) was a lead pastor, I had a hard enough time keeping up with a rapidly growing church. Caring for everyone’s needs could topple me over the edge, and as a friend once told me, the problem with human need is that there’s no end to human need.

Initially, as the leader of a small church, I took the approach of most pastors who are wired as shepherds: Scheduled as many counseling appointments and pastoral care visits as I could.

As the church grew, I started to refer most needs to the groups ministry or to a professional outside our church. Given my personality, my lack of training in counseling, and our church size, it was the best I could do.

Chances are you’ve embraced one of these two approaches and know that neither works well for you—or the church.

Pastoral care has always been the ethos of the church. Pastors aren’t only preparing sermons or running programs; they’re sitting with people in grief and confusion. The weight of unmet need becomes part of their exhaustion—something invisible, but constantly pressing.

I (Jim) see pastors embrace the approach that Carey took as his church grew—referring emotional and mental care of congregants to outside professionals.

While those partnerships are essential for complex concerns, the pendulum has swung too far. The result is a dilution of the presence of Jesus—experienced through the church—to care for the suffering.

As a licensed psychologist, I (Jim) receive referrals from pastors. I embrace the opportunity, but I see a gap between what pastors hope for their people and what I can deliver. I address anxiety, depression, and relational conflict; I can provide tools and help relieve symptoms.

But my license means I can’t be a friend. I am not part of the church’s emotional and relational community. The relief of symptoms without community will mean the return of symptoms.

We have a holy opportunity to return to our roots—a chance to recover the kind of care that once marked every aspect of the early church. This moment asks us to see with old eyes—and step into a new vision.

A Different Kind of Care

Historically, care was reserved for family, or tribe, but Jesus redefined the scope of care. The parable of the Good Samaritan was not just about kindness—it was a cultural and theological revolution: Attend to your enemy, the overlooked, and the vulnerable.

The church understood this through exhortations to care: “Be joyful in hope, patient in affliction, faithful in prayer. Share with the Lord’s people who are in need. . . . Rejoice with those who rejoice; mourn with those who mourn” (Rom. 12:12–15).

This selfless, sacrificial, presence-driven care is in our DNA as the body of Christ. It’s not just compassion. It’s a calling.

A Different Sort of Pandemic

In recent years, we lived through a pandemic—but today our pandemic is no longer a virus. It is loneliness, anxiety, and emotional overload fueled in part by social media, which likely will accelerate as AI becomes further entrenched in culture.

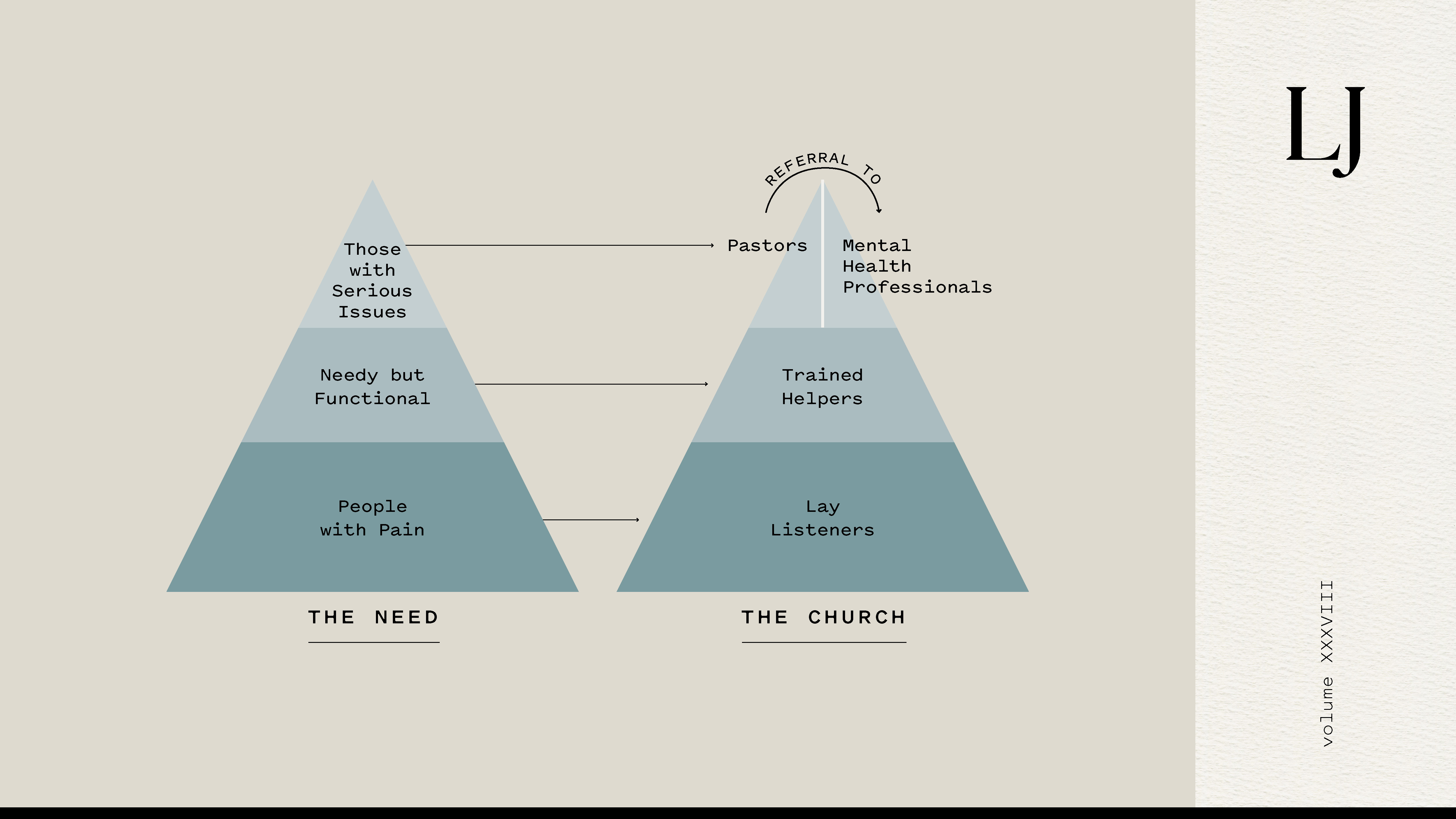

People with mental health diagnoses are more likely to seek help from clergy than from psychologists and psychiatrists combined. This isn’t because clergy are better equipped—it’s because churches are accessible. This leads to a care structure where almost every need funnels through the pastor, who refers to a professional. That can be a crucial step in getting specialized attention, but we need both the transformative life of those in the church caring for one another and professional clinicians (see Fig. 1).

Most needs in a church today are heard by the leadership before referring a person out to a clinician. In fact, in our survey for When Hurting People Come to Church (see sidebar), 88 percent of pastors believe to some degree that referring out should be the church’s primary mental health service.

And certainly, referrals are necessary. Clinicians treat severe symptoms and stabilize crises. But there are serious limitations to a church care model based primarily on referrals.

First, clinicians have ethical boundaries. As part of licensure, therapists cannot have coffee with clients. They don’t sit in someone’s house during grief. Clinicians can be costly and have waiting lists. More than a third of the US population lives in geographic areas termed “mental health deserts” with few clinicians to meet the demand.

Also, the mandate of clinicians is temporary. They care deeply for their clients, but their job is to reduce symptoms and terminate treatment. The job of the church is to care for a lifetime.

Therapy can reduce symptoms and address complex issues that require specialized care. But it cannot heal the soul or provide lasting reconciliation with God or community. For that, we have the church.

The responsibility rests with too few. Exhausted pastors can’t address the multiplicity of issues that people face, and most don’t have the capacity to provide consistent emotional support. This isn’t merely a matter of pastoral burnout, although that’s a key concern. It’s also a concern for church growth. One reason most churches don’t see growth is because they struggle to scale pastoral care.

A New Old Vision

Instead of referring out, what if churches referred within? Imagine a model where churches train volunteers to help meet basic emotional needs. Someone grieving hears, “Pete will call you. He’s on our care team and will walk with you.” In another instance, a new mom facing postpartum depression is connected to a therapist and a group of other moms who’ve been there. Such a model of care could be represented like Fig. 2.

The top tier of the pyramid are those who experience serious mental illness and other critical issues and who should see licensed professionals. A woman with acute postpartum depression needs specialized care. Her husband might need pastoral support.

The middle tier is composed of people who know loss, addiction, or marriage crises. They can be served by trained lay counselors or specialized ministries like ReBoot, Celebrate Recovery, Stephen Ministries, or GriefShare. In the base tier is everyone else—who experience discouragement, anger, fear, worry, and isolation. Trained listeners who know how to sit with suffering can meet these needs. This new (old) idea might seem unsettling given how much we have leaned into professional care. But we must face two profound realities.

The Current Realities

First, it is not possible for pastors and clinicians to provide enough behavioral, emotional, and relational support for the millions in need. That would require training hundreds of thousands of new clinicians and cost billions. The current system of mental health care—though effective—is not scalable to meet the need. Only 32 percent of pastors felt their church was effective in addressing mental health needs.

Second, there is no realistic way to address the mental health crisis without the church. There are, on average, eight churches in every ZIP code—each filled with people capable of showing up with empathy, compassion, and grace. Ninety-six percent of pastors believed that this type of Christian support was among the best ways to foster good mental health.

This kind of church engagement creates a solution to a cultural crisis and opens the door for discipleship, evangelism, and transformation through the power of the Holy Spirit.

A Simple, Powerful Path Forward: The Five Steps

We can see the need and the solution differently through a minimal cultural shift.Most churches successfully made this shift with five steps:

- Select a coordinator. This person doesn’t need answers, just a willingness to start.

- Empower the coordinator. Church leadership must give authority to those organizing care ministries. Leadership buy-in determines its sustainability.

- Use what already exists. Many ministries offer resources, training, and support. Visit thechurchcares.com for a clearing-house of these organizations.

- Prepare a team with basic skills. These are listeners trained to listen, sit with pain, offer prayer, and recognize when to refer. The goal is not therapy but Christ-centered care.

- Walk alongside the hurting. Match people with the appropriate level of care. Let volunteers support everyday needs while ensuring serious issues are addressed.

The church is uniquely positioned to meet the mental health crisis—not by replacing clinicians but by being the church: showing up, listening, carrying burdens, reflecting the heart of Christ.

When I (Carey) became a lead pastor, I wish I’d had this framework. But it’s here now. The world is hurting. Let the church be used to heal.

Carey Nieuwhof is a best-selling leadership author, podcaster, and founding pastor of Connexus Church and the Art of Leadership Academy. He is dedicated to helping people thrive in life and leadership.

James Sells, PhD, is a professor at Regent University, the coauthor of When Hurting People Come to Church, and director of The Church Cares initiative.