“What do you mean do I still believe in the Resurrection?” Derek said, avoiding eye contact with me. “I don’t know if I believe in the church anymore. I wasn’t talking about the Resurrection.” Derek had spent the past hour telling me everything he thought was wrong with the church: sexual abuse scandals, health-and-wealth prosperity-gospel swindlers, consumeristic cultural tendencies, and what has come to be called “church hurt.” Derek, once active in our church, quietly stopped attending months ago.

He’s not alone. We are witnessing what researchers call “the largest and fastest religious shift in U.S. history,” with over 40 million adults having left church communities in the last 25 years. Today 62 percent of US adults identify as Christians, and while Pew Research polls suggest the decline may be slowing, it’s dropped 9 points since 2014, and 16 points since 2007. At the same time, a massive 75 percent of US adults aged 18–34 do not go to church regularly, a culture-shifting number unless it changes. For pastors, these numbers are not just statistics. They’re names. Faces. People we’ve prayed for, counseled, and cried with. We feel their absence every Sunday. How do we minister effectively in such an environment?

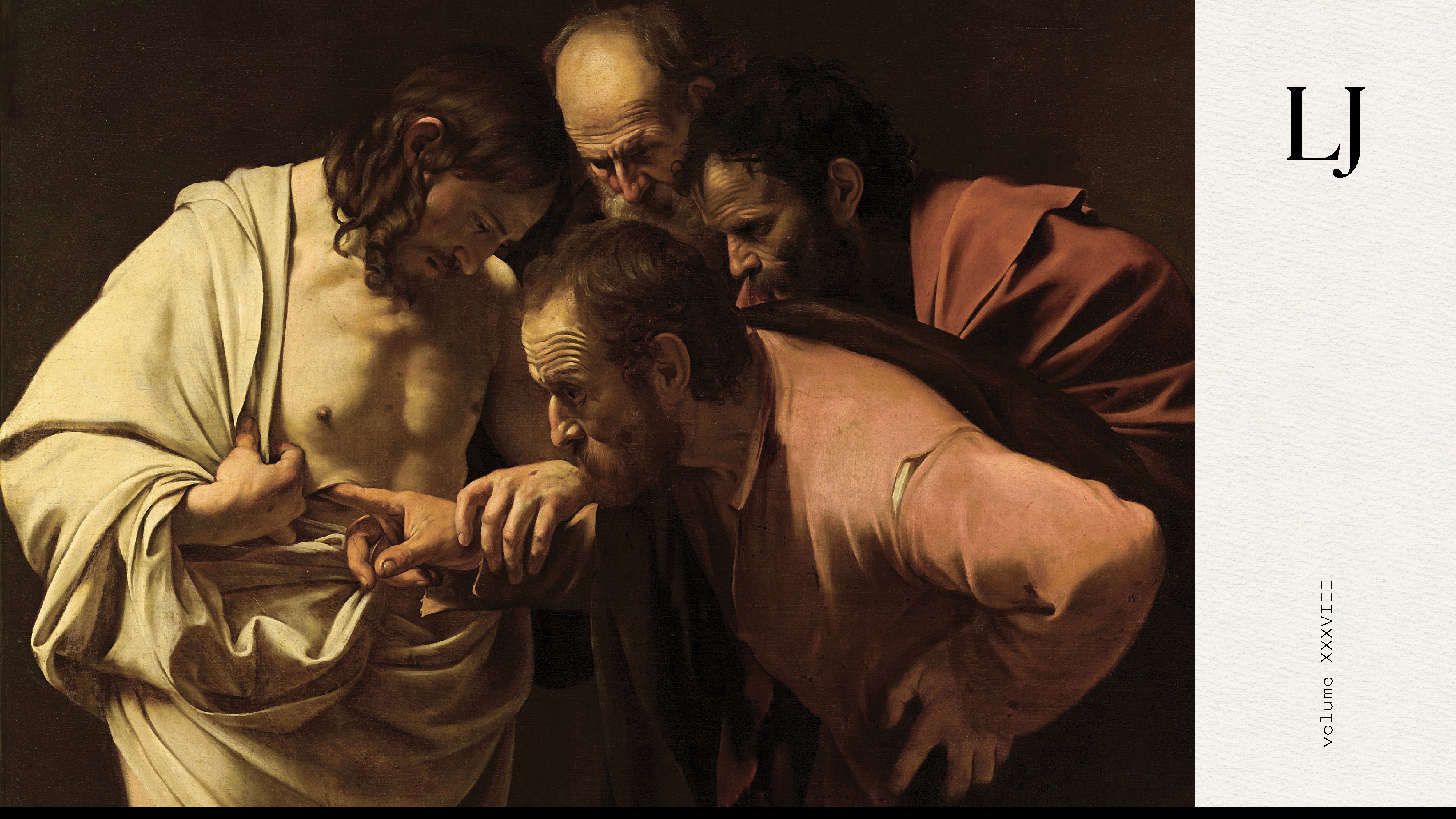

While skeptics may be as old as “Doubting Thomas,” institutional skepticism targets not merely ideas or beliefs, but the institutions that represent them. Institutional skeptics may be Bible-believing Christians who struggle deeply to trust institutions due to a wider crisis of authority, political polarization, a failure to reckon with injustice, and cultural shifts in identity formation. These have eroded our participation in and trust of institutions as the place where we grow, contribute, and care for the common good. Additionally, the amplification of scandal and abuse through social media steadily erodes trust in leadership beyond the churches or institutions in question. How can we pastor and preach effectively to address this skepticism?

More Than Technique: Pastoral Postures

Effective pastoring in this environment demands more than a change in technique. To preach to the heart of today’s institutional skeptics, pastors must cultivate and communicate authenticity, empathy, and humility—not as tactics but as embodied reflections of Christ. Before we ever step into the pulpit, these postures prime the hearts of preacher, congregant, and skeptic.

Put yourself in their shoes. If you’re skeptical of the church, you’re hyperaware of anything that seems arrogant, insincere, or defensive. The antidote, in part, is to be quick to acknowledge mistakes and the church’s shortcomings. This can be as small as admitting when the sound is not working during a service, or more profoundly, when we pray prayers of lament, using a biblical form to bring contemporary injustices before God.

When skeptics, like Derek, see pastors honestly wrestling with, repenting of, and acknowledging failures and limitations, pastors are not just embodying the gospel, they’re also giving them a leader they can trust. Prioritizing relationships over arguments and naming congregational flaws openly from the pulpit communicates authenticity. Many aren’t looking for perfect answers as much as for churches and pastors who meet their deepest doubts, questions, and struggles with compassion.

Ultimately, institutional skeptics need to be brought back to the person of Jesus and his life, death, and resurrection. My father posed a gracious, yet incisive, question I’ve found helpful with those who are deconstructing or skeptical. He said, “When someone is deconstructing, at some point you must ask: ‘Did Jesus Christ rise from the dead, or did he not?’ ” This approach doesn’t deny the failures of the church but highlights that if Christianity is true, then gathering is essential.

When Derek and I refocused on the Resurrection with this question, it provided theological guardrails, helping separate healthy critique from wholesale rejection. The pastoral challenge and opportunity of our age is not just to call people back to church, but to lead communities worth returning to—ones that practice humility, listening, and grace.

Preaching to the Institutional Skeptic

While pastoral practices help us build relational trust, preaching is how we make the truth plausible. Skeptics need preaching that’s not merely orthodox but also transparently authentic, culturally engaging, and emotionally compelling. Some pastors will say, “But I don’t have skeptics in my church, so why preach to skeptics if they’re not there?” We need to realize that inside every Christian lives a skeptic.

Paul says the “old self” and the “new self” are both in the believer: The root cause of disbelief is the core problem for both Christians and non-Christians (Eph. 4:22). Unbelief keeps non-Christians from faith and Christians from spiritual growth. Our preaching must actively counter cultural narratives that prevent belief while simultaneously addressing the deepest human longing that only Christ can satisfy. As pastors, we know that the felt needs for both Christians and non-Christians will ultimately be met in the surprising nature of grace that they have yet to fully experience.

Drawing from Pascal’s three-step process of persuasion and Tim Keller’s unpublished “27 Factors for Preaching Evaluation,” I propose the following practical framework for preaching grace in a skeptical age.

Preach Biblically: Ground Everything in Scripture and Christ

Skeptics wonder if preachers use God’s name to mask human power plays. To counter this assumption, we must root every aspect of the sermon in the text and to do so in ways that are always Christ-centered. Since the whole Bible points to Jesus and the salvation he offers as its aim (Luke 24:27), in order to preach Christ-centered sermons, preachers must not preach good advice but good news. It’s not just what I must do; it’s what Jesus has done. Jesus is not just an example to follow but rather a Savior to trust. Jesus is always the answer to our deepest longings and the fulfillment of God’s covenant promises.

There is the danger that preaching Christ from every text becomes repetitious or formulaic (just tacked on the end of every sermon), but that is usually because the beauty of the text has not captured our own imaginations enough to tell the same story in a new way each week. If Jesus is the true Prophet, Priest, and King, as well as the true sacrifice, Lamb, and temple, then our hearts will be moved to the degree that we apply our lives to this grace. If skeptics question the authority of the church due to the ugliness they see, we must root our preaching authority in the biblical text that is always beautiful.

What does this look like? I preached a sermon recently on Mark 5:1–20, where Jesus heals a man tormented by demons. I could have focused on how the people were more concerned about their industry (their pigs all jumped into the sea!) than on the healed demoniac. It’s an easy moralistic move: You should care more about people than things. But instead, I reminded the church how this points to Jesus’ salvific work: Jesus clothed this man (v. 15) because one day Jesus would be stripped naked. This man could be brought in to the community because Jesus was cast out (not just locally in v. 17, but also cosmically). Jesus destroys the power of sin and death by entering into it. Christ-centered preaching speaks powerfully to institutional skeptics because it acknowledges that their ultimate loyalty belongs not to human leaders or structures but to Jesus himself.

Preach Attractively: Engage the World

Attractive preaching resonates with the hopes and dreams of the skeptic’s heart. This involves the ability to answer the “So what?” question. When I write sermons, I imagine listening with ears of the skeptical college student, the harried single mother, and the jaded businessman, and I imagine them at every point asking, “So what? Why does this matter?” This is not a therapeutic technique; it’s an active spiritual practice deeply embodied by Jesus himself (Luke 24:19–24; John 2:1–5; Mark 5:21–34; John 11:21–27).

Every culture and time has its own constellation of hopes and aspirations that constitute a flourishing life. Unless we use vivid illustrations; cultural familiarity; and an awareness and knowledge of the listener’s beliefs, hopes, and desires, those listening to us might not think we know their world.

The preacher must not simply confront these hopes but also compel listeners to see how their hopes are most fulfilled in Jesus. Do your references show familiarity with the listeners’ world? Are you able to articulate the listeners’ beliefs and affirm as well as critique them with the Bible? The goal is not to give people what they want; it’s to give people what the Bible says they need but in a form they can understand.

Early in my preaching, I spent most of my time trying to determine what to say. To preach attractively, a preacher needs to spend more time on how to say it. What illustrations, metaphors, and examples will connect? How do I take the biblical truth and craft a compelling form?

Returning to the sermon I preached on Mark 5:1–20, I began the sermon engaging with current cultural shifts. Whereas in the past many Westerners may have found the idea of a spiritual world with angels and demons incredulous, today’s Western world has an openness to the spiritual realm. While people still care if Christianity is actually true, what’s become more culturally relevant is if Christianity is good.

Preaching attractively matters because humans are not changed with mere facts. The heart must be captured, not merely informed. Thomas Chalmers once wrote, “The best way of casting out an impure affection is to admit a pure one … it is only when, as in the gospel, acceptance is bestowed as a present, without money and without price, that the security which man feels in God is placed beyond the reach of disturbance … the only way to dispossess [the heart] of an old affection is by the expulsive power of a new one.”

But how might we preach in ways where that new affection is not only understood but also felt and desired from our hearers? Before answering this, it’s important to realize that we tend to preach in the following format: (1) Here is what the text says. (2) Here is how we must live in light of the text. (3) Go and live like that.

When we preach that way, at best we’re giving listeners a new behavior modification program and at worst we’re inviting them to respond legalistically. However, when we preach attractively, the paradigm shifts to: (1) Here is what the text says. (2) Here is how we must live in light of the text. (3) You can’t and won’t do this. (4) There is one who did. (5) Through faith in Christ, grace helps us begin to live this way. The good news of the gospel attracts us when we see that we can’t and won’t live rightly. Both Christians and non-Christians (in both moralistic and hedonistic ways) turn away from grace. Attractive preaching shows non-Christians that Christianity is not just about ethical behavior, and it shows Christians that even their good deeds can’t earn God’s favor.

Preaching Powerfully

Sermons are not lectures. When we preach biblically and attractively, our goal is to make the truth clear, but preaching powerfully makes the truth experiential. This involves transparency, emotional connection, and a movement of the gospel from an abstract concept to a personal and experiential reality.

To be transparent as a preacher is a call not to performative vulnerability but rather to living and exhibiting the gospel’s effect on our lives. Skeptics who are sensitive to hypocrisy need to see how the gospel isn’t just for those listening but is also for the preacher. This can be conveyed by varying our tone, showing joyfulness and eagerness in what we’re sharing, and also naming the hurts and cares of the world.

For example, in my Mark 5 sermon, I shared my own struggles with fear and anxiety, connecting with those who experience some version of “I know God loves me, but I don’t feel his presence.” We might intellectually understand God’s love, but we haven’t felt or experienced it so that it feels tangible. Skeptics see us demonstrating the difference between simply having a cognitive understanding of Jesus and experiencing his love and grace.

When leaders show themselves in need of grace, skeptical listeners can begin to trust leadership and church authority again. Why? Because transparency is a sign of nondefensiveness, and pastors can only embody it if they feel both fully known and fully accepted already in grace. This allows skeptics to trust again because the church isn’t claiming perfection: It’s offering acceptance to all those willing to admit their imperfections.

Only the presentation of the wonders and beauties of Christ’s care will move one from being able to merely describe God’s love to tasting and seeing it (Ps. 34:8; 119:103; Heb. 6:4–5; Ps. 27:4). The aim of preaching is not just to stir up feelings but to bring truth to bear on the heart. For example, when we use the word justification, no mental image moves most listeners. But when we speak about our adoption into the family of God as sons and daughters (Rom. 8:15), that’s an image that moves us into greater truth. We are showing, not just telling. When I’m experiencing the gospel personally, I’m also most able to reveal it powerfully in my preaching.

Where does this leave the preacher? Thankfully, this isn’t just a list of more to do: Listen better, work at humility, and preach differently. If institutional skeptics return to the church, it’s not because of institutional or pastoral perfection. Rather, it is in the humble, honest sharing of our collective brokenness and our reliance on Christ’s beautiful and transforming grace that may prove healthy soil for the Spirit’s work.

Pastor, if you’re weary—confronted daily with skepticism, cultural confusion, political entanglements, and the ever-present sense that even your most heartfelt efforts feel insufficient—may I offer you a word of encouragement? The decline in church attendance is not necessarily a failure of your ministry. Faithfulness cannot be primarily measured in numbers.

Root your pastoring, preaching, and ministerial identity in something far more solid than success. You must root it in Jesus. Jesus ministered among deep institutional skepticism too. Both religious and political institutions at the time failed and hated him, yet he did not succumb to despair or cynicism. Instead, Jesus built a community of imperfect followers who trusted not in their own or institutional perfection, but in Jesus’ transformative grace. This is our task too: not to build perfect institutions, but to form communities of grace, humility, and hope.

Eventually Derek returned, but he never pointed to one profound moment as why he came back. “I need grace,” he said simply, “and I need to be around others who know they need grace too.” What your people need is not perfect churches or flawless services but rather your faithful presence and extension of grace. Derek was not lowering his standards by returning to the church; he was setting them higher—in Christ.

At the same time, don’t surrender to fatalistic narratives about inevitable secularization. Missionary Lesslie Newbigin pointed out when a culture becomes less religious, God may be using this movement to clean away faux religiosity, so people must contend with the nakedness of their precepts in a world that doesn’t make sense without God.

The larger movement of secularism in the West may be part of God’s process to rid us of a fake spirituality that was never actually built on grace. As a pastor, your calling is primarily not to successful metrics, but to faithfulness. Like Jeremiah who proclaimed God’s Word for decades with little visible fruit or Moses who wandered for 40 years in the wilderness, in any given season we may not see the fruits of our labors. Jesus himself lived the most faithful ministry, yet when he died, no one would have said he was successful.

We are not ultimately judged by what is seen, but what is unseen. That means we can know each night as we lay our heads down on our pillows that our Lord says to us, “Well done, good and faithful servant!” (Matt. 25:21, 23).

The global church continues to grow in many regions, and even in the West, research indicates that most who have left the church did not do so because of negative experiences but because of transiency. In fact, half of those who left remain open to returning if they’d just receive a personal invitation.

Your labor is not in vain. Every pastoral conversation that humbly listens and offers hope; every sermon that faithfully proclaims Christ biblically, attractively, and powerfully; and every effort to create a community of authentic love centered on the need for grace matters, even when results aren’t immediately visible.

This is ultimately what made Derek return: grace embodied, grace proclaimed, and grace lived out. Pastor others, not needing to be perfect but pointing to the only one who is perfect. Preach, not because you’ll do it perfectly, but because it’s centered on the perfect one. Admit your failings and flaws, but show how Jesus offers something profoundly better—a community of grace and transformation despite our failings. Experience and grow in the grace you want your church to experience and grow in. Only the beauty of Christ’s sacrificial love and the reality of his resurrection will capture hearts hurt by institutional and personal failure.

Take heart, weary pastor. You are not alone. Your ministry matters infinitely more than you can know and rests infinitely less on your abilities than you can see. The harvest is still plentiful, and the Lord of the harvest has not abandoned his field—or you.

Michael Keller is the founding and senior pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church, Lincoln Square and a council member of The Gospel Coalition. He also serves as a fellow for The Keller Center for Cultural Apologetics.