Just outside my house, there’s a bird that sings throughout the night. She sings like a morning bird. Though surrounded by darkness, she sings as though there is light.

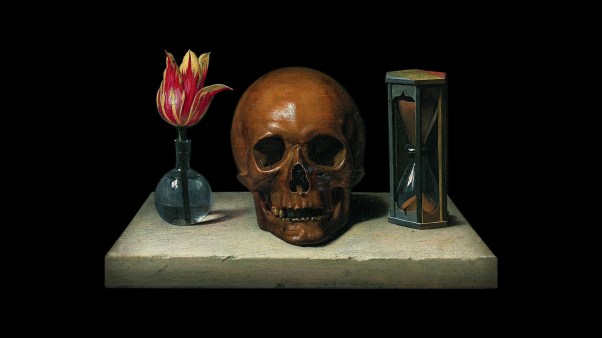

Night descends on us in many forms, some more horrific than others. Imagine you’re lying in bed, desperately ill. You have been coughing and vomiting for days. You’re convinced you only have a short time to live. For good reason: Hundreds of people in your village and tens of thousands throughout the land—people and animals—have already died after showing these symptoms. John Kelly described such a moment from 500 years ago: “For a brief moment in the middle of the fourteenth century, the words of Genesis 7:21 seemed about to be realized: ‘All flesh died that moved upon the earth.’”

The name of his book tells us what he was speaking of: The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time. And yet, during “the most devastating plague of all time,” a night of unimaginable darkness, one woman heard the morning bird sing.

Her name was Julian of Norwich. We know very little about her—even her name is a guess, taken from the church where she lived in a monastic cell. A close reading of her writings suggests that she was probably born around 1342 and lived into her 70s. She likely came from a wealthy family in Norwich, the second largest city in England at the time.

The bubonic plague was tragically common during her lifetime, killing 50 million people in Europe, some 60 percent of the entire population. Julian may have lost her whole family in one epidemic, and may have suffered from the plague herself at age 30. Whatever she actually suffered, it was plague-like in that she and her loved ones assumed she was breathing her last.

While on her deathbed, she experienced a series of intense visions of Jesus Christ. When she recovered, Julian described her visions, and these writings became known as the classic The Revelations of Divine Love. It is believed to be the earliest surviving book written in the English language by a woman.

One of the more extraordinary things she said God told her during this time—when the black plague raged throughout Europe and her own body was rapidly failing her—was this: “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well.”

It was like hearing a morning bird sing in the blackest part of the night.

It would be all too easy to imagine Julian thinking, All shall be well? Really? Have you not seen the death of our families, friends, and strangers by the millions? Have you not smelled the stench of sickness and death, and the hopelessness that covers us like dense fog? It looked like God was pouring out his wrath, that the end of the world was at hand. But Julian had a “foolish” faith that clearly heard the promise of God instead of the cacophony of death around her.

Julian is but one instance of God singing like this, as he does all through Scripture. To paraphrase Revelation 21:5 into Julian’s cadences: “I will make all things new, all things new. I will make all manner of things new.” This promise is like a small iceberg that sinks the huge ship of despair. A heart that is firmly anchored in hope can unwaveringly smile and stare even the black plague in the face: “And we know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose” (Rom. 8:28).

Think of Abraham and Sarah. They were old, long past the childbearing years but still childless, and this in a culture where it is a curse to be childless. And yet they heard the inconceivable promise that a great nation would come forth from them. Abraham and Sarah doubted this promise for a time—who wouldn’t? But in the end, they trusted in the morning song instead of the night, living with hope when circumstances didn’t warrant such confidence. And so they discovered this: “Hope does not disappoint, because the love of God has been poured out within our hearts through the Holy Spirit who was given to us” (Rom. 5:5, NASB).

Back to that verse in the Book of Revelation: as one commentator put it, “The good news at the heart of the book of Revelation is the announcement ‘I am making everything new’” (21:5). Leading up that that climactic statement are visions of beasts and blood and all manner of suffering. John was writing to seven congregations, some of which were receiving the blunt end of the hammer of persecution. And he says that the same Lamb of God who died for the sins of the world is making all things new. It’s not only that things are often terrible now and will be better later, but even in the midst of the terrible now, all things can be experienced as being well. As Jesus put it, referring to his bloody death on the cross: “And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself” (John 12:32). That is the most unjust and horrific thing—the death of the Son of God on the cross—and yet people will be drawn to the Prince of Peace, and thus enjoy the peace that passes understanding.

Julian, Abraham, and the apostle John are three morning birds, among many others, who sing through the night. They hoped against hope (Rom. 4:18). The lyrics of indie pop duo Capital Cities’ international hit song, “Safe and Sound,” put it well: “Even if the sky is falling down / I know that we’ll be safe and sound” and “Even if we’re six feet underground / I know that we’ll be safe and sound.”

In Julian’s day the sky was falling down and millions were going six feet underground. But she was reassured:

. . . the Spirit showed me a tiny thing the size of a hazelnut, as round as a ball and so small I could hold it in the palm of my hand. I looked at it in my mind’s eye and wondered, “What is this?” The answer came to me: “This is everything that has been made. This is all Creation.” It was so small that I marveled it could endure; such a tiny thing seemed likely to simply fall into nothingness. Again the answer came to my thoughts: “It lasts and it will always last because God loves it.” Everything—all that exists —draws its being from God’s love. (From All Shall Be Well: A Modern-Language Version of the Revelation of Julian of Norwich by Ellyn Sanna, Anamchara Books, 2011)

The world is like a tiny nut held in the hand of a God committed to preserving it until it blossoms into its destiny. We can fight that God-ordained destiny and rebel against it, as some inexplicably and sadly do. Or we can trust and hope in the God and the Lamb who promise that for those who believe, all will be well because he is making all things new.

Dylan Demarsico is a freelance writer from Southern California, finishing studies at Liberty University.