On August 28, 1963, more than 200,000 blacks and whites from all over the United States gathered for a gigantic civil-rights demonstration in the nation’s capital. It was the largest demonstration in the history of Washington, D.C. Young and old, black and white, Jew and Gentile marched shoulder to shoulder from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial. The purpose was to demand passage of a civil-rights bill and immediate implementation of the basic guarantees of the Declaration of Independence and the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution.

Regarded by many as the apex of the nonviolent civil-rights movement, the march brought together all of the major civil-rights organizations and many religious groups. Among the strong supporters of the march were the American Jewish Congress, the National Conference of Catholics for Interracial Justice, and the National Council of Churches. Never before had leading representatives of the Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish faiths identified so visibly with black demands. It also marked the first large-scale participation of whites in the civil-rights movement, and the first determined efforts by the white clergy.

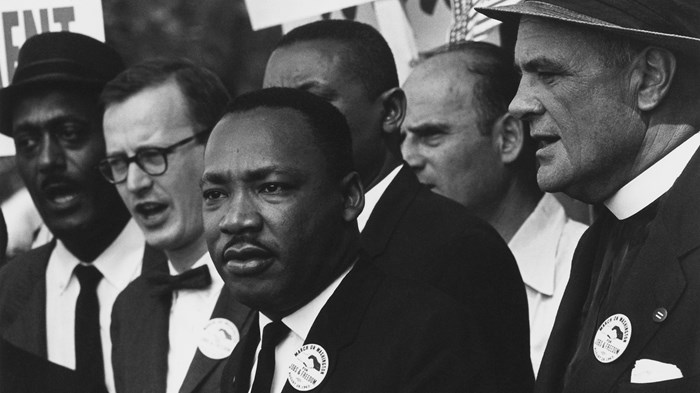

“I Have a Dream”

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave the keynote address at the march. In his memorable “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered in the style of the Southern black Baptist preacher, Dr. King articulated a dream big enough to include all Americans. “I have a dream,” he said, “that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.… I have a dream my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character … and when we allow freedom to ring … we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children—black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Catholics and Protestants—will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last, free at last, thank God almighty, we are free at last.’ ”

Millions of white Americans heard for the first time the message Dr. King had been trying to articulate since the civil-rights movement began in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955. This speech, which is perhaps the best-known and most-quoted speech that Dr. King delivered, made his voice familiar to the world and lives as one of the most moving orations of our time. Millions of people accepted the dream as their own and the dreamer as the conscience of the nation.

King’s Legacy

The March on Washington was better covered by television and the press than any event in Washington since President Kennedy’s inauguration. Usually African-American activities commanded press attention only when violence was likely to occur. The march was perhaps the first black-organized activity that received coverage commensurate with its importance.

In addition to being a summation of years of struggle and aspiration, the march also symbolized certain new directions, such as a deeper concern for the economic problems of the masses, and more involvement by white moderates in the black struggle for civil rights. Over the following ten months, the white churches proved to be the most effective champions of the civil-rights bill. They exerted considerable influence on Congressional representatives from the Midwestern and Rocky Mountain states, where the black population was relatively small. The result was the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which reiterated the constitutional rights of African-Americans by mandating equal voting privileges and access to public accommodations, jobs, and housing.

The March on Washington etched a place in history for the black Baptist preacher from Atlanta, Georgia. Combining his philosophy of nonviolence with the folk religion and revival techniques of his black religious tradition, Dr. King projected a new image of the black church. His tremendous appeal to the black masses lay in his ability to use familiar religious language and old biblical images to articulate their passion for racial justice. The sonorous words of his dream delivered at the Lincoln Memorial are now an important legacy of hope for millions of Americans, black and white, who celebrate once a year his life and contributions.

Dr. Wesley A. Roberts is pastor of Peoples Baptist Church of Boston and a member of the advisory board of Christian History.

Copyright © 1990 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine.

Click here for reprint information on Christian History.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month