I have not suffered greatly for my faith. I worship God freely, where and how I choose to do so. My property has never been confiscated because of my convictions. I have never been threatened or harmed because of my faith. The greatest pain I have suffered as a Christian has been self-inflicted—sorrow over sins committed, discouragement over recurring temptations.

These minor sorrows are assuaged by the comfort the parable of the Prodigal Son offers. When I read this story, it is the image of loving, open arms of the waiting Father for his raucous, repentant son that leap off the pages. But this interpretation has something to do with the context in which I read the parable. If I had grown up as a member of a persecuted, endangered church, I might read and interpret it differently.

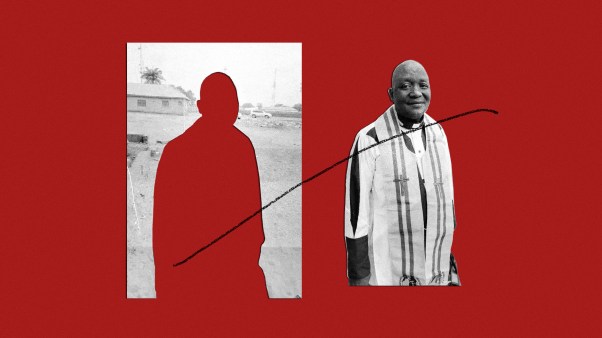

For the early church, persecution sporadically erupted against the Christian community, inflicting intense abuse and suffering. How, I ask myself, would I have reacted to an order to sacrifice to the emperor, particularly if I knew that simply a pinch of incense sprinkled on the coals of a Roman altar could save my life, family, and property? Or what if I were put on trial, as in the case of the beloved Bishop Cyprian in the middle of the third century:

The proconsul Galerius Maximus ordered Cyprian to be brought before him . …

Proconsul: “Are you Thascius Cyprianus?”

Cyprian: “I am.”

Proconsul: “Have you allowed yourself to be called ‘father’ of persons holding sacrilegious [that is, Christian] opinions?”

Cyprian: “I have.”

Proconsul: “The most sacred emperors have ordered you to sacrifice [to the emperor as a god].”

Cyprian: “I will not do it.”

Proconsul: “Have a care for yourself . …”

Cyprian: “Do as you are bid. There is no room for discussion when the issue is so clear.”

Proconsul: “You have lived for a long time holding sacrilegious opinions. You have gathered a large number of accomplices around you in your blameworthy conspiracy. You have proved an enemy to the Roman gods and their sacred worship. Nor have the pious and most sacred Emperors Valerian and Gallienus, the Augusti, and Valerian, the noble Caesar, been able to recall you to the observance of their rites. And so since you have been convicted as the instigator and ringleader in most atrocious crimes, you shall be an example to the accomplices in your crime. Your blood shall be shed in accordance with the law.”

After saying this, the proconsul read the verdict from his tablet: “We command that Cyprianus be executed by the sword.” Bishop Cyprian said, “Thanks be to God.”

Cyprian persevered in his faith to the very end and received the martyr’s crown.

But what of those who had lapsed in their faith and offered sacrifice to the emperor? Was a second chance, a new beginning, possible for those who had so gravely sinned? Could the ruptured and violated relationships between Christians—between those who had courageously confessed their faith and those who had rejected it—experience restoration? Could those who had lapsed in their faith be forgiven? What does the parable of the Prodigal Son have to say to this situation?

Same story, different perspectives

Some early Christians, many of whom lived under constant stress because of their uncertain status in the Roman world, reacted differently than I do to Jesus’ parable.

Tertullian, a gifted theologian writing roughly 150 years after the apostle Paul, argued that the parable of the Prodigal Son must never be applied to Christians. Could a Christian sin in such a rebellious, high-handed manner and still be forgiven? Tertullian said no. To extend forgiveness so broadly would release a torrent of sin within the church. Not only “adulterers and fornicators,” but “idolaters, blasphemers, and renegades … every class of apostates” would use the parable as an excuse for sin. “Who will worry about losing what can be so easily regained?” Tertullian asked. “Security in sin develops an appetite for it.”

Tertullian’s rigorous position appealed to some early Christians because it seemed to strengthen the church’s resolve against sin, a resistance sorely needed in the Roman Empire. For many years the early church inhabited a wider world that viewed it with great suspicion as an upstart religion bent on undermining Roman society.

Others besides Tertullian agreed that the parable of the Prodigal Son didn’t apply to Christians who turned apostate and then wished to return to the fold. The presbyter Novatian, while acknowledging that God had the power to forgive even Christians who lapsed in a time of persecution, insisted that those who had sinned in such a grave manner could not be readmitted to the church’s fellowship. For Novatian, the church consisted of only the katharoi, the “pure.” How could those who had tainted themselves with the sin of apostasy validly or safely rejoin Christ’s spotless body?

Novatian’s hardline position, though, was vigorously opposed by other church fathers, almost all of whom were pastors or bishops in the church. Ambrose, a leading bishop in Italy, argued that to deny people—Christians or non-Christians—the possibility of forgiveness, even for the gravest of sins, was to rob them of all hope. The Prodigal Son had found his way home by the path of repentance. Where would his repentance lead him if he could never go home again?

Jerome, a church father well known for his sandpaper personality, observed the context of the parable of the Prodigal Son in Luke’s gospel, commenting that if Christ welcomed “publicans and sinners,” how could the church refuse them? The very rhythm of the Incarnation demanded that the church be a forgiving, welcoming community: “What clemency can be greater than that the Son of God should be born a son of man, that He should endure the tedium … of gestation, await the arrival of birth, be wrapped in swaddling clothes, become subject to His parents, grow through successive ages, and after the insulting words, blows, and scourging become for us accursed on the cross, in order to free us from the curse of the law, being made obedient to the Father, even to death?”

Jerome insists that God the Father’s foreknowledge encompassed and envisioned the return of his wayward sons and daughters, a journey home illustrated by Jesus’ parable and made possible by the Incarnation. “God with whom all future events are already past and who knows beforehand all that is to be, runs forward to his coming and by His Word, which took flesh by a virgin, anticipates the return of His younger son.”

Augustine, a contemporary of Jerome, readily admits the returning son did not deserve his father’s love. Has there ever been a repentant sinner that did? Augustine reasoned that the younger son’s recognition of his unworthiness demonstrated his once proud heart had become humble, malleable before God’s glory and purposes. “This unworthiness, this glory we do not deserve, the younger son acknowledges when forced to by his need. The younger son, I repeat, acknowledges this unworthiness when wandering far from his father’s home … he acknowledges God’s glory, but only when constrained by want. And because through that glory of God we have been made what we were not worthy to be, he says to his father: ‘I am not worthy to be called your son.’ Unhappy as he is, he obtains happiness through humility and shows himself worthy by the confession of his unworthiness.”

Gregory of Nazianzus, a church father writing in the East in the late fourth century, asked how Christians such as Novatian could withdraw the possibility of confession, repentance, and forgiveness from any person and still retain the gospel. What hope would such harsh judges possess if measured by their own standards? “Do you not accept repentance? … Do you not shed a tear of mercy? I hope you may not encounter such a judge as yourself! Do you not revere the kindness of Jesus, who ‘bore our weaknesses and carried our diseases,’ who ‘did not come to call the righteous, but sinners to repentance,’ who ‘wished for mercy rather than sacrifice,’ who pardons sins ‘seventy times seven times’?”

What especially irked Gregory about those who refused to welcome home repentant sinners was the selective standard these moral rigorists seemed to apply in their judgments. Novatian, for example, apparently was willing to forgive those who struggled with greed, but he was much more reluctant to forgive those guilty of sexual transgression. Gregory wryly noted that Novatian “harshly condemned sexual immorality, as though he himself was not made of flesh and blood. What do you say to this? Do my arguments persuade you? Come on, stand here on our side, on the side of human beings: let us magnify the Lord together.” Gregory reminded his reader of the forgiveness David received after his adultery with Bathsheba and his murder of Uriah; indeed, the forgiveness of “the great Peter, after he succumbed to human weakness at the time of our Savior’s passion,” demanded that the church mirror that same mercy, compassion, and forgiveness.

Spiritual blindness engendered by pride, Gregory insisted, rather than a concern for holiness, lay behind the rigorist party’s unreasonable demands. Had they forgotten that they, too, were mere human beings, apt to succumb to temptation if left to themselves? Gregory openly acknowledged his own weakness apart from Christ: “I confess myself to be a man, a changeable creature of unstable nature. … I know that I am myself ‘beset by weakness,’ and that I shall receive in proportion as I give.”

Second chance forgiveness

Let us not be too quick to dismiss the moral rigorists. In ways I echo Tertullian’s misgivings about blanket forgiveness. Hasn’t such a message encouraged moral laxness and irresponsibility? Tertullian surely thought so. Many Christian leaders share my dismay over the spiritual health of the church today. I want to pronounce God’s judgment on the church’s shortcomings. I want the church to be a holy, pure, committed, sacrificial, righteous community. I want evil to be judged. I want to see Christ’s kingdom established in power and purity. If this means that we must speak harshly to some and exclude those who have violated the community’s moral standards, so be it. If we continue to dilute Christ’s call to holiness, faithfulness, and commitment, will the world around us ever take us seriously? The moral rigorist in me says no.

But here is a different thought experiment: Where would I be today if I had applied Tertullian’s perspective and moral standard to my own life? As I recall my attraction to the gospel as a college student in the late sixties, I remember two aspects of Christ’s message raised my hopes: the possibility of forgiveness and the possibility of genuine moral change. While Tertullian might have offered forgiveness to me as a repentant pagan, his rigorism concerning postbaptismal sin would have discouraged me. Deeply ingrained sinful patterns dominated my life. They would not change overnight. I knew what I was capable of doing. What if I made a serious mistake after my conversion?

Was this hope? If so, it was a slim hope, one filled with doubt and anxiety. I needed a story that would encourage me to genuine confession, repentance, and change, without threatening me with expulsion from the family if I fell into sin and needed to find my way home. I needed a safe, secure context for facing the hard work that lay ahead for me—to face honestly years of self-deception and moral confusion.

Haunted by the elder brother

The attitude and language of the moral rigorists are eerily similar to the attitude and language of the elder brother in the parable—the brother who sees no reason to welcome the younger prodigal home. The elder brother complains to his father that he had been “slaving” for many years. He had “never disobeyed” his father’s orders. Surely if any one deserved a fattened calf, it was he. In other words, he was “pure.”

The father’s response no doubt shocks the older brother. “My son … you are always with me, and everything I have is yours.” Calves, robes, rings—all belonged to the older son. Why? Because he was a member of the family, just as was the younger prodigal. Obedience and hard work were appropriate within the family structure, even praiseworthy, but the older brother’s position as a son was not predicated on his hard work and obedience. The older son had not learned that family language is largely the language of love, forgiveness, and reconciliation, not that of moral obligation. Or, as Gregory reminds the followers of Novatian, calling them to reform their thinking and behavior: “Come on, stand here on our side, on the side of human beings.”

If we continue to dilute Christ’s call to holiness, will the world around us ever take us seriously?

The older brother’s inheritance was guaranteed because he was a son, a member of the family. He could neither earn nor deserve it. Of course the fattened calf must be slaughtered and a party thrown for the younger son. He was a member of the family, not a hired hand or slave. Yes, the younger brother and son had made terrible mistakes, wounding his father’s heart, but his status as son had never changed. It couldn’t. He had thought he could return to the family circle as an outsider, a family slave, but that was impossible. Once a son, always a son, even when lost in a foreign land. All that the father asked and longed for was that the son would come to his senses, change his mind about his behavior, and come home.

It is this insight that church fathers such as Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome, and Gregory of Nazianzus grasped so well. They never denied the importance of integrity. They knew that unconfessed sin was spiritual poison and could contaminate individuals and the life of the church as a whole. They stressed the importance of church discipline. Still, the fathers clearly understood that moral rigorism and the language of moral obligation left too much unsaid. The family language of the gospel provided a different moral and linguistic context for dealing with sin.

Sons and daughters, the fathers realized, could make terrible mistakes. As Gregory put it, we are all “changeable” creatures “of unstable nature … beset by weakness.” If so, only the gospel, with its offer of forgiveness and restoration to the family’s fellowship, could remedy the brokenness of the human heart. The entire story is one of grace, grace undeserved, unexpected, unearned. In Jerome’s words, “grace, which is not a payment due to merit, but has been granted as a gift.”

Only in Christ and within Christ’s body, the church, can we experience forgiveness and freedom from the past’s mistakes. Only within Christ’s family can we learn to live as he desires. Only within the Trinity’s embrace of love can we learn to face what needs to change. Indeed, as Jesus stressed in his parable, repentance, confession, and forgiveness are always possible—an occasion for celebration in heaven and on earth.

Christopher A. Hall is associate professor of biblical and theological studies at Eastern College, St. Davids, Pennsylvania, associate editor of the Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, and author of Reading Scripture with the Church Fathers (InterVarsity Press).

Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.