“Welcome to the game,” said high school student Marian Ward over the loudspeaker before a Friday night football game last September in Santa Fe, a suburb of Galveston, Texas.The daughter of a Baptist pastor then offered this prayer:

Lord, thank you for this evening. Thank you for all the prayers that were lifted up this week for me. I pray that you watch over each and every person here tonight, especially those involved in the game, that they will demonstrate good sportsmanship, Lord, and that we’ll have safety. Just be with the fans, that they will exemplify good behavior as well, Lord. And just be with each and every one of us as we go home to our respective places tonight. In Jesus’ name I pray. Amen.

UNHOLY END RUN

The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to rule, in Doe v. Santa Fe later this year, whether that brief prayer violates the constitutional ban on the establishment of religion. An appeal has landed in the high court’s lap because of an ill-reasoned ruling of the Federal Appeals Court, Fifth Circuit, banning pregame prayer. Judge E. Grady Jolly, in his lone dissent, said the ruling “achieves the jurisprudentially rare result of offending not only one, but three provisions within the First Amendment.” Indeed, that opinion was an unholy end run around the rights to free speech and unfettered religious expression, and the ban on established religion.In the Santa Fe Independent School District, administrators designated a specific time slot for one student to speak publicly before weekly football games. Each spring, the student body selected the student by secret ballot. The individual student had free rein to speak briefly on the school’s public-address system.In its majority opinion, the federal appeals court objected to this procedure on several grounds: Because the school’s policy was highly restrictive, it was not truly a public forum for free speech. Because the policy allowed prayer that was sectarian and proselytizing in its content, the school was endorsing “a particular form of religion.” In addition, the ruling found that a football game is a constitutionally inappropriate place for students to pray because it is “hardly the sober type of annual event that can be appropriately solemnized with prayer.”

PROTECTING CHURCH, NOT STATE

American lawmakers and judges have interpreted the religion clause of the First Amendment for more than 200 years, evolving standards that generally have allowed a high level of religious freedom. But the application of standards established a generation ago, as in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), has put the court into the highly arbitrary, hairsplitting, and unending business of setting boundaries for public religious expression.Our public education system persists as the nation’s foremost battleground for First Amendment cases involving religion. Much of the focus has shifted to what is constitutionally allowable for students to do with their religion in public. Students in public schools may meet with other students for prayer and Bible study, carry Ten Commandments textbook covers, wear WWJD bracelets, organize Christian clubs on campus, and hand out religious literature, among other things. Teachers and other employees of public schools, in contrast, may not use their roles to advance a religious cause or to sponsor worship.The pregame-prayer case looks at whether public student prayer before a sporting event violates the establishment clause. The original purpose of the establishment clause is to protect churches from the state (establishment historically undermined the church’s freedom to speak freely and prophetically), not the reverse. The establishment clause can be misinterpreted easily. The ban on state religion must not be employed to make public speech (including prayer) inoffensive to everyone. It is not a tool to protect the sensitive feelings of atheists or adherents of minority faiths.Finally, the establishment clause does not give the state license to permit only “Golden Rule” civil religion, to censor specific religious convictions while blessing those with more tepid or tolerant belief systems.

ENDING RELIGIOUS PREJUDICE

Christians and adherents of other faiths should choose their words with as much sensitivity as student Marian Ward. But the roots of Doe v. Santa Fe show that good intention is not enough. During a history class in 1993, a teacher handed out fliers that advertised Baptist revival services. A student asked if non-Baptists could attend. After the student explained she was a Mormon, her teacher openly criticized her church for its “cultlike nature.” Then her classmates reportedly said, “It’s kind of like the KKK [Ku Klux Klan], isn’t it?” In the context of such outrageous insensitivity, Marian Ward’s commendable prayer for good sportsmanship and protection from injury took on an oppressive and threatening aspect.The court can ban pregame prayer, but it cannot enforce a moratorium on religious bigotry. Because religious bigotry has many less visible manifestations, faithful Christians who find themselves in the majority should move with grace and care toward outsiders.Americans are more religiously diverse than ever before. If students are allowed to pray before the game, they must discipline themselves to encounter each other’s deepest convictions and discover a new wellspring of mutual respect and tolerance.Illustration by Darryl Brown

Related Elsewhere

In March, ChristianityToday.com reported that a U.S. federal court in Florida ruled that student-led prayers before graduation ceremonies were constitutional. In January, we reported on two women who are trying to keep the government out of parochial schools. Last year, we looked at God on the gridiron.More details on the Marian Ward case are available at the Washington Post, World magazine, ABC News, the Los Angeles Times, the Christian Science Monitor, and CNN. Opinions on the case can be found at Americans United for Separation of Church and State, the Claremont Institute, The Sporting News, and the Family Research Council.School Prayer is an extensive Web site that reports the controversy over school prayer in Mississippi. Additional news reports on school prayer can be found at Yahoo! Full Coverage.The 1999 U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decision in the Santa Fe case is available online.The ACLU has written a brief for the Santa Fe case which argues that prayer before public school games is unconstitutional. The American Center for Law and Justice, which is representing the school district, has argued otherwise. Texas Governor George W. Bush and Texas Attorney General John Cornyn have filed a brief before the Supreme Court supporting student-led prayer before school sporting events.The PTA and the National Congress of Parents and Teachers have published a guide for parents unsure about the role of religion in the public schools. President Clinton and U.S. Secretary of Education Richard Riley have also weighed in on the issue.

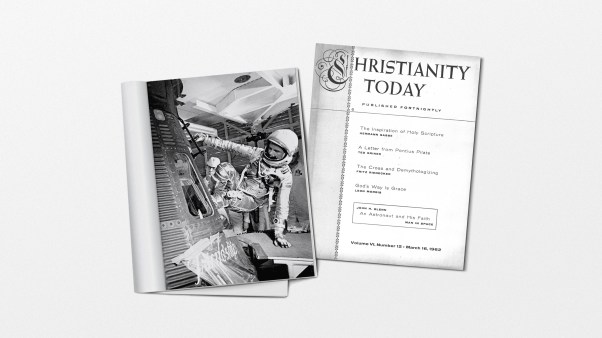

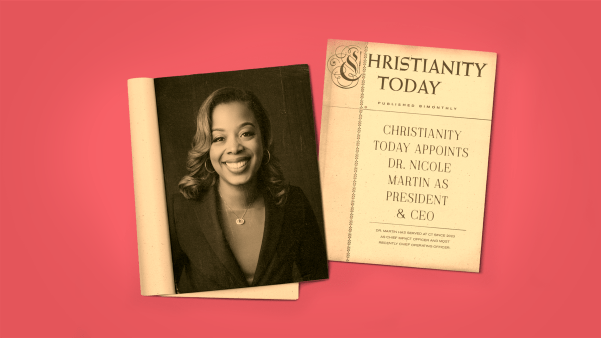

Copyright © 2000 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.