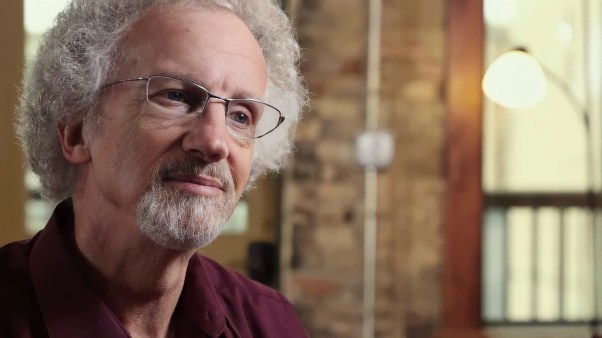

The life of Vernon Grounds, who died September 12 at age 96, spanned the birth, growth, and maturation of the evangelical movement in North America. During his seven decades of ministry, he helped shape contemporary evangelicalism in significant ways: by building a key institution, Denver Seminary; by challenging evangelicals to wed social action to evangelism; and by pointing the way to a new and thoroughly Christian approach to psychology. But before he did those things, Grounds gave himself to preaching a reasoned and reasonable faith.

While a student at the newly formed Faith Theological Seminary in Delaware, Grounds became part of a group that included such later evangelical luminaries as Arthur Glasser, Kenneth Kantzer, Joseph Bayly, and Francis Schaeffer. The Faith Seminary community, like its theological guru Carl McIntire, was committed to defending the intellectual foundations of our supernatural faith.

While a young pastor in Paterson, New Jersey, Grounds produced his first book, The Reason for Our Hope, based on a series of radio talks. He ably made the case for faith in the supernatural Christ and the credibility of his Word. With this book, Grounds began his ongoing emphasis on apologetics. Over the next few years, in tandem with Edward John Carnell of the newly formed Fuller Theological Seminary, he was at the forefront of an intellectual renaissance among American evangelicals.

While pastoring in Paterson, Grounds also pursued a Ph.D. in psychology at Drew University. There he began writing a dissertation on "The Concept of Love in the Psychology of Sigmund Freud." It took him 20 years to complete the dissertation, but his topic presaged his engagement with culture and his break with fundamentalism.

Grounds's intellectual star power attracted a wider audience, leading him out of the pastorate to the newly formed Baptist Bible Seminary in New York, where, in the fall of 1945, he began as dean and professor of theology and apologetics. In 1951 he accepted a call to serve as dean and then president of Conservative Baptist Theological Seminary (later renamed Denver Seminary). He led that institution over the next 28 years, modeling "servant leadership" years before the phrase became popular. He inspired Denver's faculty, staff, and constituents and helped the seminary grow from 30 students to over 300. Remarkably, he accomplished this through periods of financial strain and vicious attacks from fundamentalists, while pursuing an itinerant ministry that led evangelical apologist Bernard Ramm to compare him to the peripatetic John Wesley.

Grounds penned these lines to describe the ethos of Denver Seminary: Here is no unanchored liberalism—freedom to think without commitment. Here is no encrusted dogmatism—commitment without freedom to think. Here is vibrant evangelicalism—commitment to think within the limits laid down in Scripture.

He took his own words to heart and went on to write five more books and nearly 200 articles related to the veracity of the Christian faith and its application to the needs and issues of the day—particularly in the widely divergent arenas of social ethics and Christian counseling. Without Grounds's contributions in these areas, evangelicalism as we know it would not exist.

Redemptive Radicalism

During the 1960s, with its rapidly changing culture that was increasingly hostile to the gospel, Grounds challenged fortress-minded evangelicals to combine social action with personal conversion. In 1969 he published Evangelicalism and Social Responsibility, a short landmark work based on a 1967 series of lectures. In this book, which Ron Sider has called "far ahead of its time," Grounds declared the Savior's love for humanity as the driving force behind a "social justice" that Christians were to proclaim and practice.

Grounds's lectures came four years before the Chicago Declaration of Evangelical Social Concern and the founding of Evangelicals for Social Action, and seven years before the landmark Lausanne Covenant urged evangelical social responsibility. The lectures were a harbinger of the current evangelical consensus that Christian mission must embrace both evangelism and social action.

During this time of ferment, Grounds told Christianity Today magazine readers that while "God has his own program mapped out for changing the world by the personal intervention of Jesus Christ, who will return to establish the kingdom of heaven on earth," there was "no biblical reason for concluding that enormous evils cannot be significantly changed before our Lord comes back." We are to be "God's saboteurs," he said, as well as "spiritual subversives, duplicating the redemptive radicalism of those first-century Christians who were condemned for turning the world upside-down."

Through the 1980s and '90s, Grounds kept his focus on social justice and probed the issues of nuclear proliferation and Christian peacemaking.

At the end of the century, he told the readers of Prism that the "gospel brings us under the lordship of the Savior who measurelessly extends neighbor responsibility. Christ makes our in-group not just the church but the whole family of humanity," Grounds continued, "refusing to let ethnicity, ancestry, geography, ideology, or even theology limit our responsibility to our neighbor."

Denver Seminary institutionalized Grounds's social justice commitment in the Vernon Grounds Institute of Public Ethics, which hosts an annual conference on current issues.

Without the contributions of Vernon Grounds to social justice and Christian counseling, evangelicalism as we know it would not exist.

'Care Was His Greatest Gift'

Grounds was also one of the main forces behind the rise of Christian counseling. His study of love in the thought of Freud and Erich Fromm helped him realize the limits of human-centered therapies and to advocate the healing power of God's unlimited love. "Calvary love," he called it.

He began an M.A. program in counseling at Denver Seminary that did not follow the clinical pastoral education model used at the mainline seminaries. He built instead on evangelical theological foundations while drawing on the best from secular psychology and psychotherapy. His integration of therapeutic and biblical truth is best seen in the final two chapters of his 1976 book Emotional Problems and the Gospel. Over time, Denver's program attracted admiration and emulation from many in the larger evangelical community.

Denver Seminary's approach to Christian counseling grew from Grounds's deep commitment to the care of souls. As his biographer, the late Bruce Shelley, noted, "Care was his greatest gift. He was almost supernaturally adept at it. He preached the gospel. He read and understood psychology. He taught crisis counseling. But he lived pastoral care." At an individual level, Grounds's ministry of affectionate mercy was nothing short of God's grace to thousands of people.

Grounds once described himself as "sanguine, phlegmatic, and hopefully empathic." Those who had the privilege of enjoying his presence always labeled him as kind, compassionate, wise, and witty.

Grounds retired from the seminary presidency in 1979. He became president emeritus and then chancellor. Functionally, little changed. He spent the 1980s and '90s doing what he done before: traveling, speaking, teaching, writing, presiding over Evangelicals for Social Action, and, above all else, counseling wounded souls. Rather than retreating to a sunny climate and a gated community, Grounds traveled abroad to see human suffering and injustice up close. He raised questions about the threat of war in light of Christ's call to make peace. As always, he called attention to broken people and modeled personal involvement with them.

Never a strong administrator, Grounds was wise enough to admit that his job was "not to ride herd on details or be a fundraiser but to be a catalyst, interpreter, planner, and an agent of reconciliation." He showed that he was all these things and more by his long, fruitful life of loving service and godly influence in the cause of Christ.

Scott Wenig is associate professor of applied theology at Denver Seminary.

Copyright © 2010 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Previous articles on Vernon Grounds include:

Denver Seminary's Vernon Grounds Dies at 96 | Vernon Grounds, chancellor of Denver Seminary and a prominent founder of the evangelical movement, died on September 12 in Wichita, Kansas. He was 96. (September 22, 2010)

Vernon Grounds: A Man for All Ages | Today I feel fatherless. (September 21, 2010)

A Long, Warm Glow | A respected evangelical elder on the life of faith. (May 1, 2006)

Ministry For A Lifetime | What does "ministry for a lifetime" look like? To me, it looks like Vernon Grounds. (July 18, 2002)