I’m not a collector, but I love the Nativity sets that begin appearing this time of year. Whether ornate, simple, ethnic, crafty, plush, porcelain, enormous, or fit-in-eggshell teeny—show me a crèche, and I’m a kid on Christmas Eve again.

But even I admit there’s a point at which crèches cross into the realm of weird. Nativities starring chickens, for instance. Or trolls. Or zombies. Or any of the bizarre kitsch that youth ministry veteran Mark Oestreicher has found for his ongoing list of “the worst and weirdest nativity sets,” including the Meat Nativity—made of bacon and sausages on a bed of hash browns.

Discerning Christians in the West often protest the mishandling of Christmas: the tacky, irreverent, quaint, and theologically-problematic distortions that pass as the gospel, not to mention as art. While I find the Meat Nativity hilarious, I realize a hotdog Jesus takes the carne of the Incarnation a little too far. But I wonder if, in our hurry to correct such spiritual shallowness, we miss a vital opportunity to engage the broader culture at a moment when our neighbors are actually focused on the right thing: the story of Jesus.

Humans are story-formed people. Our first sense of who we are and where we fit within an often-confusing world comes through the narratives our communities tell us. And this narrative engagement is not simply a developmental stage only for children: it’s a function and framework of the imagination, that part of our human mind that makes connections, discovers patterns, and processes meaning in ways that include but transcend reason. You can’t get three pages into Scripture without both using your imagination and being enriched by the imaginations of others—all through the medium of story.

Sometimes stories are the best way to reach those who are otherwise disinterested.

Yet whenever I sniff out theological distortions wafting around popular culture, storytelling is not my first instinct. My first instinct is to clear the air, to proclaim in loud, aggrieved tones—on social media, from the podium, or in my writing—that such distortions obstruct the truth.

If someone asks me a catechetical question (“What is the meaning . . . ?”), they are likely to get a doctrinal response. If someone expresses even mild curiosity about Christianity, like many of us I’m tempted to share a statement of faith rather than a story about Jesus. Despite the fact that similar questions in the Hebrew Scriptures are met with stories—as in Deuteronomy 6:20–25—and that Jesus himself often answered direct questions with indirect parables, providing no further explanation, it’s easy for many of us to assume narratives are meant for children or, at best, for homiletical flourish.

Granted, there are moments when theological conversation is vital: when I’m teaching a Sunday school class, when I’m asked a question by someone who desires a theologically reflective answer, or when a fellow Christian makes an absurd, problematic comment in public, leading to fallout at the local level. But such clarifiers, while important, are not the only or always the most effective mode of Christian engagement with the world. Sometimes stories are the best way to reach those who are otherwise disinterested.

Truth through the Back Door

While I’d love to tease out the theological implications of making a crèche baby Jesus from a shotgun shell, I sense this is a moment when our culture offers a corrective by persistently, tactlessly, and childishly insisting that the story itself is what matters. After all, the Nativity doesn’t exist in order to deliver another message or principle or idea. It exists to deliver Jesus. And there he is, right in the middle, every time. He may be portrayed as a chicken—and why not? In Narnia he’s a lion—but he’s there. Yes, there are many ways in which our culture distorts and misunderstands the gospel. But in this one weird instance, I think our culture—with its appropriation of a simple biblical narrative—is on to something. It has let the truth slip in.

My family and I were once given a Guatemalan crèche whose holy family looks nothing like middle-class suburbanites. Instead, it represents the very economic strata that Jesus came from: those who, in Howard Thurman’s words, have “their backs against the wall.” We also have a hand-crocheted Nativity, which—rather than expressing don’t touch to little children, as collectible porcelains often do—invites small hands to pick it up, play with it, and enter and enact the Christmas story.

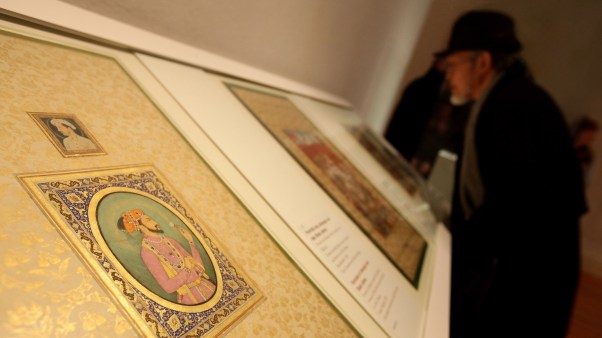

And then there’s art—the kind that has taken time and discipline and a robust engagement with both culture and the Christian faith. Recently I’ve had the privilege of editing an anthology of poetry and fiction for Advent, Christmas, and Epiphany, in which I’ve encountered one astonishing, beautiful, and raw version of the Nativity after another. Take, for example, these lines from Susanna Childress’s poem “Bethlehem, Indiana,” featuring a modern-day mother and child:

. . . Say we were

to come upon these two as they share a moment while Joseph, who,

according to St. Brigit’s account, cannot keep their only candle lit

and so has stepped away to shake his lighter, slap its plastic

shell against his jeans: you would realize, then, from the marquee

illuminating NO next to VACANCY, visible from the palm-sized window

eye-high in the custodian’s closet, that you’ve found them in the Motel 6,

or perhaps its periphery, since there’s no faded bedspread here, no bed,

no lamp, no faucet or sink, no folded white washcloth, the undulating

highway nearer to them than the front desk, whose single geranium

slouches toward discolor.

The poem ends by inviting us to seek the baby on a stretch of Midwestern highway, where we

pull into the Quick-Mart for directions. The man at the counter

whose young wife has just brought in her infant son for a visit

won’t look up when the bell over the door jangles our arrival, not

at least, until he notices our faces, which are either somber or exultant

as we say, We’re just passin’ through or We’ve come to see.

Stripped of sentiment and its usual props and costumes, the story is made strange enough to see and understand as if for the first time. And this is precisely where the Holy Spirit can make a move. When the front door of reason is locked and double-bolted against the gospel, as it is for so many of our neighbors, the back door of the imagination often stands wide open.

Perhaps our task as Christians during Christmastime is not to rush to confront and correct our culture’s distorted theology but to let the story itself be the point. Rather than turn away in disdain from our culture’s mishandling of the gospel, we have an opportunity to tell the story anew, to share the “good spell”—the meaning of gospel—with those who, for some odd reason this time of year, are actually interested.

I suspect this is one of those cases in which a little child just might lead us all.

Sarah Arthur is the author of numerous books. She most recently edited Light upon Light: A Literary Guide to Prayer for Advent, Christmas, and Epiphany (Paraclete Press).