What are the most important qualities of a society that allow economic prosperity to take root? A lust for learning and knowledge? A blistering work ethic? Increasingly, academic research has highlighted a characteristic that may surprise many: Social trust.

Trust and its inseparable counterpart, trustworthiness, are themes that run strongly throughout Scripture. Trustworthy people are continually held in high esteem throughout the Bible (Exod. 18:20, Neh. 13:13, Dan. 6:4, Luke 19:17, 1 Cor. 4:2, 1 Tim. 3:11). Trust and trustworthiness are fundamental to healthy relationships; they are hallmarks of spiritual maturity. But academic research has only recently begun to grasp why they are so fundamental to economic prosperity.

The importance of social trust has been driven home as my family and I live for six months in a small village in Oaxaca, Mexico. The value of social trust is made salient by its absence, like being oblivious to your mother’s savory cooking until you leave home. Mexico is a wonderful country, rich in resources, history, tradition, art, and culture. But it is not a country rich in trust. Trust in government, in politicians and police, even among one’s fellow citizens is as sparse as water in the Sonoran Desert. These are not casual observations. Lamentably, they are how the data speak.

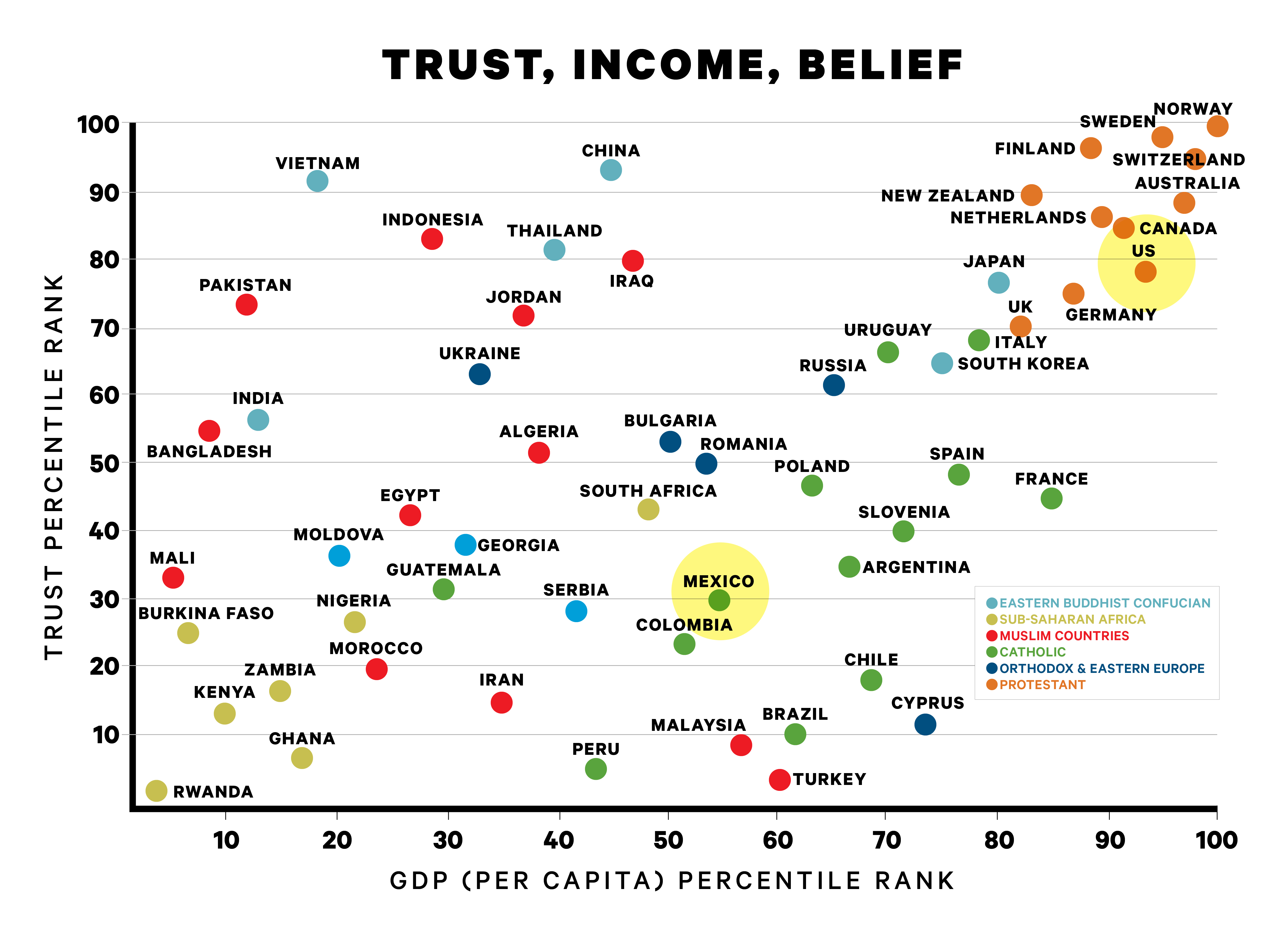

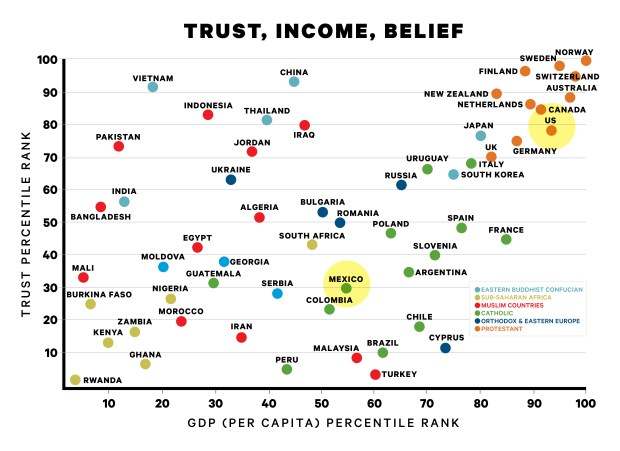

For 35 years, social scientists of all stripes have been obtaining data on trust and trustworthiness through the World Values Survey. In this carefully representative survey, 400,000 people across 100 different countries are asked: "Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?” For example, while 74.2 percent of those in Norway affirm the first phrase (most people can be trusted), only 15.6 percent do so in Mexico, where the second phrase is affirmed (that is, you need to be very careful in dealing with people).

The figure I constructed from the World Values Survey data and World Bank statistics on per capita income illustrates the strong correlation between trust and economic prosperity. Of course one must always be careful with correlations. It may be that people become more trustworthy as they become richer. Or it may be that a third factor causes both trust and economic prosperity to take root. But in a series of papers using fancy econometrics to tease out causality, researchers have confirmed the relationship: social trust has significantly fostered economic prosperity.

In a series of papers using fancy econometrics to tease out causality, researchers have confirmed the relationship: social trust has significantly fostered economic prosperity.

It is possible that the level of general trust in a society may have spiritual roots. The clustering of trust, income, and religious belief in the figure cannot help but give one pause. The sociologist Max Weber emphasized the work ethic inherent to Protestant Christianity; perhaps he should have emphasized the trustworthiness ethic.

The very definition of trust is related to the giving of power to others and thus has the potential for abuse. We see this in multiple avenues of everyday life. I trust you by sharing a private thought. You now have the power to hurt me by sharing it with others, but by sharing this with you, I am trusting that you will not abuse this power. But I share with you so that you, and I, and our relationship, may profit from it. Trillions of these simple, trusting exchanges produce the network of human relationships.

We entrust politicians and police with power over us and other citizens. We empower them so that they may govern effectively and protect us. But public officials may harm us with this power by abusing it and using it for their own gain. On the other hand, millions of leaders employ this trust for the common good to create the building blocks of healthy institutions and civic societies.

In a similar way, anyone in business understands that virtually every transaction involves some degree of trust and vulnerability. Do I honor the credit you have extended to me, or do I default on your goodwill? I know the quality of the goods I sell to you better than you do. Do I use this power to misrepresent what I’m selling, and so exploit your trust? The more individuals one can trust, the greater is the potential for business to prosper, for economies to thrive. Billions of trust-based transactions form the atomic structure of economic prosperity.

Where does the general lack of social trust originate in a country like Mexico? In the historical abuse of power at multiple levels: government, business, labor unions, and sadly even the church. But more deeply, its origin lies in a Latin trait that is regarded admirably, even envied by many North Americans: an overarching loyalty to extended family, close friends, and clan.

Indeed our family marvels at this aspect of Mexican culture here. In the village in which we live in Oaxaca, extended family and friends gather for baptisms, birthdays, weddings, funerals, quincieañeras (a celebration in honor of a daughter who turns 15), and days that commemorate the family’s patron saint. These gatherings are frequent and expensive; weddings, for example are said to cost up to a year of family income. Gifts are given to guests. (Our neighbors, for example, received at a friend’s wedding the big fat turkey that gobbles in their yard.) The breadth, depth, and regularity of family relations in countries such as Mexico are astounding by North American standards. It creates an extraordinary level of trust within the family network that evolves and strengthens through reciprocal acts of generosity and favor.

I know that you can be trusted within your network, but if I know that you cannot be trusted outside of your network, then why should I trust you?

The problem arises as the commitments to those within the family network take precedence over commitments to those outside of it. Indeed the very ethos of faithfulness to the network can create a moral justification for abuse of power to outsiders. Countless examples exist in Mexico’s history of presidents and governors giving the green light (so to speak) for family members to pillage the public treasury. At lower levels, police and petty bureaucrats solicit bribes to bring home more to the family. As everyday citizens fully understand one another’s supreme loyalty to their respective family networks, it creates a paralyzing lack of trust between anonymous citizens.

I know that you can be trusted within your network, but if I know that you cannot be trusted outside of your network, then why should I trust you? Moreover, because those in the government are principally loyal to those in their own networks rather than the population they ostensibly serve, I cannot even trust the government to enforce your promises. Therefore we will not do business. Multiplied over the whole business sector, an economy stagnates.

Mexicans are not ignorant of the domestic trust problem, and indeed have created an almost paralyzing set of remedies to address the domestic trust and trustworthiness issue: Extended family often live together in a small set of houses surrounded by a common wall to keep untrustworthy outsiders at bay. The wealthier the family, the higher the wall. Speed bumps or “topes” lie at fantastically narrow intervals on city streets because drivers are not trusted to reasonably obey speed limits. (Note: do not hold hot coffee between knees while driving in Mexico.) Even remotely formal documents must be officially notarized to prevent forgery. Bank deposits are scrupulously monitored by the government to prevent money-laundering. A new public campaign has police cars, schools, and government buildings emblazoned with single-word admonishments that proclaim “honesty,” “integrity,” and “truthfulness.”

Here is where the influence of a Christian ethos is most powerful in the establishment of trust: In the context of a genuine Christian commitment, the greater ethical claims toward 1) God and 2) Neighbor supersede the claims of family (Mark 12:31, Luke 14:26). Indeed a summary of New Testament teaching is anything but a “focus on the family.” It is an ethical focus that lies primarily outside of the family. Jesus calls for an ethos that supersedes loyalty to close kin. His mother and brothers were “those who hear the word of God and put it into practice” (Luke 18:21). The injured man for whom the Samaritan risks his life is not a member of his family or tribe (Luke 10:33). Jesus mocks the reciprocity that exists within social networks, correctly identifying this apparently beneficent behavior as a mere illusion of altruism: “If you love those who love you, what credit is that to you? Even sinners love those who love them” (Luke 6:32).

In this respect, how can Christians be the yeast that helps leaven society with trust? Here are three possible points of action. First, we can live out trust and trustworthiness. In what ways have we ourselves failed to follow through on our commitments to those outside our networks of close family and friends? We need to ask God to make us worthy of the trust of others and repent of untrustworthy behavior.

How can Christians be the yeast that helps leaven society with trust? Here are three possible points of action.

Second, we can learn how to trust. Those of us with at least some degree of power (or at least authority) are often faced with opportunities to trust an arguably “borderline-trustworthy” person with a task. How can we help shape trustworthiness? By trusting the person—in faith—remembering that in God’s eyes the task or issue at hand may be secondary to the character and relationship development that may occur through it. Explicitly telling this individual that you trust her because you see her as trustworthy helps cement her self-identity as a trustworthy person; it encourages her actually be trustworthy. Consider the way of Jesus toward his (borderline-stable) disciple Simon, renaming him “The Rock” (Petros) as he entrusted him with leadership of the church (Matt. 16:18), re-forming Peter’s identity as characterized by stability and trustworthiness.

Lastly, we can support organizations that understand the importance of trust and trustworthiness in economic work among the poor. There are two main types of faith-based organizations that help promote trust. The first are those who minister in the area of social reconciliation in places where violence or abuse has occurred and where trust has ground to a halt. Organizations such as the Christian Community Development Association, the AMOS Project, and African Leadership and Reconciliation Ministries work in the area of racial and social reconciliation domestically and abroad, and they are worth of our support. In the second category are organizations working against poverty by focusing on early childhood development, character values, skills, aspirations, and the development of mature leadership. While selected interventions that provide things for the poor can be effective, in the final analysis the development of human beings is paramount to the long-term hopes of poor countries. Organizations such as Compassion International, Partners International, and New Day for Children understand this and are likewise worthy of our support. Through a commitment to trust and trustworthiness and supporting organizations with similar values, we can have a strong impact on our world both through our personal example and our giving.

Bruce Wydick is professor of economics at the University of San Francisco and Distinguished Research Affiliate at the Kellogg Institute of International Studies at the University of Notre Dame.