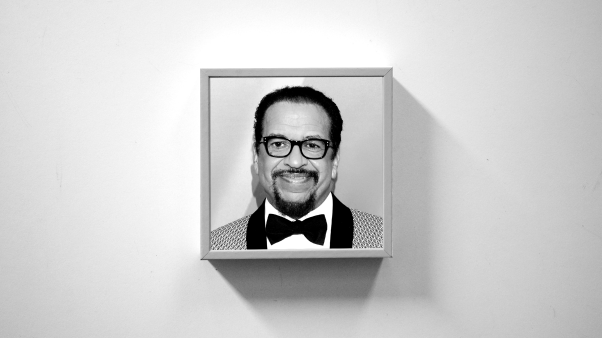

A psychology professor at Wharton Business School, Adam Grant probes motivations and inspirations to get at the heart of work.

His research reveals unexpected glimpses of humanity and character, like how generosity can help leaders get ahead (his 2013 bestseller Give and Take) and how the rest of us are more like iconic innovators than we think (his latest book Originals).

Packed with the stories behind the success and failure of memorable projects from Seinfeld to the Segway, Originals was the basis for Grant’s top-ranked TED talk on creativity and generated acclaim from figures like author Malcolm Gladwell and director J. J. Abrams. It’s what inspired me to explore innovation among Christians for our July/August cover story, CT Makers.

Grant offers up his expertise in organizational psychology—how individuals behave in groups and in the workplace—to discuss different ways evangelical faith may affect how we think and create.

A lot of Christians express a sense of calling, the idea that they believe God has called them to work to solve a certain problem, help a certain group of people, or go into a certain field. How does this sense of calling help or hurt original thinking?

The idea of calling when it comes to creativity is a double-edge sword. On the one hand, when people feel called, they are often willing to work harder, smarter, longer than they would have otherwise. We know that persistence is so important to creative breakthroughs. The idea that you would keep going when you encounter a wall; calling can be a big part of that.

On the other hand, there is also this sharper edge of a calling that a couple of colleagues have studied… One challenge is that it’s associated much more with a sense of duty than intrinsic motivation. The problem with duty is that it often leads to a sense of pressure that interferes with creative sparks. The most productive creative processes are usually driven by curiosity and interest and enthusiasm in the work, as opposed to a sense that I’m going to be letting others down or letting God down if I don’t do this.

The other potential downside of a sense of calling is sometimes people who feel called to a certain line of work feel that some kinds of tasks, that they have a hard time connecting to their calling, are beneath them. We know also from a lot of research that some of our best creative leaps happen when we’re doing mindless work and we’re distracted a little bit from focusing all of our conscious attention on the problem, and that’s where we do this creative, non-linear thinking. If only certain tasks are aligned with your calling, you may not want to do some of the repetitive work that helps with creative thinking. [For more on this concept in action, see this study on calling among zookeepers.]

There’s also a moral dimension to what we chose to do, a belief that our work can help bring about good in the world. How does that come into play?

A few years ago, a colleague and I published a series of studies showing that when you take concern for helping others and add that to intrinsic motivation, people actually become more creative. If people are just curious in the work, they follow what’s interesting to them, and that leads them to over-invest in the ideas that are novel and fun, as opposed to the ones that are actually useful and beneficial to others.

When you add in the second motivation of, “Not only do I find this work fascinating, but I also really care that it helps someone, then you’re much more likely to select the most practical and potentially beneficial of your novel ideas, and that’s good for going from “I have a new idea” to “I have something that’s worthwhile.”

In a chapter on groupthink, you write, “Cultural fit has become the new form of discrimination.” Programs have emerged specifically for Christian startup founders in part because there’s a sense that Silicon Valley culture isn’t welcome to conservative, evangelical faith. Is this “outsider-ness” ever a good thing or does it limit us?

The answer is both. Initially, I bet the benefits might outweigh the costs. As people find that they don’t fit into the Silicon Valley culture, for example, they are much more likely to question assumptions that are taken for granted. The ability to think differently is heightened by being an outsider. On the other hand, as time goes on, you end up running the risk of groupthink, of replicating the same problem as within Silicon Valley, but with a different set of values. In seeking to differentiate yourself from places that you don’t belong, make sure diversity of thought is one of your core values. If you don’t do that, you’re going to see similar challenges.

What would be your advice to people who worry they have something that disqualifies them from success? Maybe they think that they don’t have the money or the connections or the personality to make it big.

There’s plenty of evidence that those things are useful, but there are so many good examples of people who brought enough grit and perseverance to the table that they were able to overcome those disadvantages. I would hate to think of someone who says, “Because I don’t have the same advantages as other people, I’m not going to try.”

Everyone who ever questioned his or her ability to be creative has a choice between two different ways of thinking about failure. I could start a business that goes bankrupt. I could try to invent something that never gets off the ground. I could create a bunch of art that no one ever buys. I’ll feel like a failure, and I’ll embarrass myself. But what we see is that in the long run, it’s not our actions but our inactions that we regret.

In your book, you debunk all these myths about how we see creative people, and it really humanizes these hero-figures. I started to think that if we see creative people as distinct from us, we excuse ourselves from not doing anything amazing with our own lives.

Yes. If I say, “Well, those people are fundamentally different from me. I’m not a risk-taker; I’m a procrastinator. I’m not a first-mover; I feel doubt and fear. I have some ideas that are probably not-good,” then I give myself a pass, and I don’t have to wonder what might have been. If you recognize a lot of these great innovators and change-makers in the world are no different than the rest of us, you no longer have any excuse not try.

How does our family makeup factor into our decision-making around work and creativity?

If one of your steering reasons for working is you care about your family, then you have a stronger motivation to make sure your job is secure, and being creative one of the best ways to make yourself valuable in an organization. Part of what makes you indispensible and irreplaceable is you have ideas that others don’t.

Also, oftentimes, the more people care about their families, the more they care about setting a good example, being a good role model for their kids, and building a legacy. Work is a place where a lot of people do that. There’s a lot to be said for the motivational boost that comes from passion for family. I would be willing to bet the earlier that kicks in, the more broadly you think about what kind of contribution you could make.

Some of the legendary originals mentioned in your book worked for or on behalf of the church. What do you make of religious conviction when it comes to originality?

I was intrigued by the number of people who felt pulled in multiple directions because of their religious convictions. Why did Martin Luther King Jr. not want to lead the civil rights revolution? Because he was committed to being a pastor. Obviously, he had a higher calling, which he ultimately chose. Copernicus, he was afraid to release his ideas about the earth revolving around the sun because of fear of persecution from the Catholic Church. So often, people are constrained by the shackles of religious rules they are trying to follow, as opposed to the underlying principles that led to those rules. A lot of people break free from the limits of their own making… when they step back and ask themselves, “What does this belief stand for? Why does this matter?” That is a critical distinction that people have used to pursue their novel ideas.