Throughout this raucous political season, evangelicals have been known more for whom we might elect than for being citizens of the kingdom of heaven. High-profile evangelical and charismatic leaders have expressed unheard of levels of enthusiasm for a man known for being a casino owner, a serial adulterer, liar, and business fraud. Other evangelicals, hopeful for economic transformation in an unequal society, stand bewildered at the choice between an unscrupulous billionaire and a politician who takes six figures from Wall Street for 30-minute speeches.

Polls regularly show the two leading candidates are among the most disliked nominees in recent memory. Meanwhile, we are repeatedly told (for how many elections in a row?) that this is the most important election of our lifetime, and that it will determine the course of our nation. Even those of us who are confident about whom to vote for may find ourselves staring into a bottomless chasm of despair when the election is over. If the vote doesn’t go our way, are we left with anything more than defeat and tears?

Looking for a King and a Kingdom

One evening some years back, one of my sons curled up in my lap while I reclined in my reading chair. As he scanned my book piles, his eyes fell upon the spine of N. T. Wright’s How God Became King. Wright argues that in the Gospels Jesus comes as the God of Israel in the flesh, showing back up among his people to establish his reign as he promised in the prophets. God’s gospel heralds could finally shout “your God reigns” (Isa. 52:7), for Yahweh was now revealed as “king over the whole earth” (Zech. 14:9).

“But I thought God has always been King?” my son said. It was a terrific observation. Didn’t the psalmist say that God was enthroned over everything? Of course he is. And the New Testament tells us that the most important political fact anyone can ever know is that God has established his Son as the ruler of all things and is actively putting all things under his feet. That Son will one day, fully and finally, establish God’s eternal kingdom. Only then will we be able to say that government of the people, by the people (who will reign with him, Rev. 2:25–27; 5:9–10), and for the people shall not perish from the earth.

The local fiefdoms of this world are given room to run with their rebellion for a time, but it’s not easy living in a world full of rebellion. The politics of a broken world leaves us feeling less like shouting about what has already taken place, and more like lamenting what has not yet transpired. In the midst of tragedy and injustice, Israel’s prophets and the New Testament authors encouraged God’s people to look up to a God enthroned in heaven and look forward to a day when his kingdom is fully established and rebellion is no more. Peter tells us that God’s patience in fully bringing this kingdom is his mercy: Rebellious people still have the chance to turn to this patient Lord, finding a grace that will save them from the coming judgment.

In his work on the kingdom of God, Scot McKnight has explored the way in which Christians lose patience and fuse the kingdom of God and the present transformation of the world. To be sure, we are certainly given the task of prayerful labor and faithful presence in the world, and most Christians believe this can involve serving in politics and casting votes. However, we are easily tempted to be not only in the world, but also of the world. Seen in this light, disenchantment with frantic political efforts to establish the kingdom today can be a gift if it helps us look to a future kingdom.

Moreover, there is another aspect of God’s kingdom that receives scant attention, even though it is prominent in the Bible and a goldmine for helping us live in a broken world: It’s the very nature of God himself. If we want to understand the kingdom of God and live in peace in the midst of earthly kingdoms, we should start with an understanding that the God of the Bible is King, Emperor, and Lord.

Contemporary approaches to this deity are vastly removed from the Bible’s reigning paradigms (wordplay intended) for the God who inhabits its pages. Even the conceptions of God held by most Christians are often disconnected from the imperial nature of the metaphors and concepts applied to God in the Bible. We desire relationship, not hierarchy. We feel the need for affirmation and love, not authority and lordship. We pick and choose our metaphors and theological truths so that they offer us a more comfortable God. However, when we view these alternative metaphors in their ancient contexts, they often turn out to be more imperial than we imagined—but no less comforting for being royal. These perspectives on God bring with them helpful resources for placing today’s political challenges in the light of eternal imperial realities.

God as Friend

For instance, we might prefer to imagine ourselves as God’s friends rather than his loyal subjects, recalling the remarkable statement that Abraham was “God’s friend” (James 2:23, with 2 Chron. 20:7 and Isa. 41:8 behind it). It is true that in the Bible and in the ancient world more broadly, friendship carries elements of equality and sharing. Friends are granted certain rights and privileges that hint at intimacy denied to others. But the friendship dynamic did not mean that relationship trumps or diminishes royalty.

For instance, in John 19 the Jewish leaders assert that if Pilate releases “king” Jesus, he would no longer be able to call himself a friend of Caesar. Friendship in an imperial context doesn’t imply mere companionship. Rather, it’s a description of a patron-client relationship in which one party clearly owes his standing to the patronage and goodwill of greater authority. If Pilate doesn’t show his allegiance by punishing rebellious usurpers, he’s not being a good client who exercises rules on behalf of his “friend” the emperor.

In return, Pilate’s status as the emperor’s friend implies much more than a follow-back on Twitter or a card each December. Likewise, the emperor’s friends receive favor and protection and a place of great status and honor in the kingdom. God is this kind of royal friend that we need, who promises to care for us regardless of what elections and life’s circumstances bring our way. There are no events outside the purview of this friend. He uses the evil and unjust leaders for his purposes. He can use disappointment and even outright hostility to shape us into the image of his Son.

In Jesus’ final intimate instruction a few chapters earlier, he calls his followers “friends,” and he juxtaposes this special status with the more menial role of servant or slave (John 15:15). But in the previous verse he ensures that our conception of friendship doesn’t leave lordship behind: “You are my friends if you do what I command” (15:14). Friendship doesn’t eliminate royalty; it is shaped by it. But this is terrific news! An imperial context for our friendship means that we receive favor, protection, and status from a Lord far greater than Caesar.

Love and Lordship

Some would urge us to leave royal metaphors behind in favor of a verb: Love is the thing we need to know and do. We can leave lordship and law and loyalty behind as relics of an old covenant or outdated worldview.

But in an imperial context, love is a verb that signifies allegiance to a lord, and the God of Israel requires his subjects to love him. Deuteronomy and covenants from neighboring cultures agree: Love for a lord is another word for obedience. Jesus shares this imperial framework for love: “If you love me, keep my commands” (John 14:15, 21–24). And he doesn’t use the command to love God and neighbor to do away with lordship, law, or fidelity. Rather, he insists that the law and prophets hang on such commandments (Matt. 7:12, 22:34–40).

The call to love God and our neighbor is sometimes presented as an alternative to political engagement. But it’s better to see the command to love as an invitation to meaningful participation in every sphere of life, including politics. We are to love with everything we have and everything we are, and that must include our vote. So participation in the political process is not ruled out when we prioritize love. Rather, our vote can become a way for us to love God and others, even if it is ineffective or less valuable than many other actions.

Holy Father

Still others prefer to emphasize God’s mystical presence, stressing encounters with God’s mystery, glory, and otherness found in visions and the temple. But with very few exceptions, whenever someone in Scripture gets a glimpse of God, they encounter a king seated on a throne: “In the year that King Uzziah died, I saw the Lord . . . seated on a throne” (Isa. 6:1). God’s presence in the tabernacle and temple is that of a King “enthroned among the cherubim” who rules, protects, and judges his subjects. If our mysticism doesn’t ultimately involve encounters with a king, it’s not biblical mysticism.

Nor is an understanding of God’s identity as Father complete unless we consider its imperial significance. As Aristotle observed, every ancient household was a miniature monarchy. “Father” was an important label for royalty who could protect and provide for their people. Despite a 20th century scholarly conjecture that birthed thousands of sermons, “Abba” doesn’t mean “Daddy.” It’s merely the Aramaic term for Father, but it’s no less spectacular for being that: The early Christians used this Aramaic word as a reminder that those united with the Messiah get to share in the royal identity of the Son who had the right to place “Abba” on his lips. If our father is the Emperor, then we are destined to be kings and queens who share the rule of his enthroned Son over all things (Rom. 8:15–17, 2 Tim. 2:12, Rev. 2:25–27).

These images highlight God’s sovereignty. In a number of places where we see God enthroned, the passage is meant to serve as a balm for those who are struggling with political turmoil. This King raises up and deposes leaders and has a destination in mind for every fiefdom: The kingdoms of this earth will one day “become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Messiah” (Rev. 11:15). In the meantime, subjects of pagan kings as well as citizens of modern democracies should learn that God “is sovereign over the kingdoms on earth and gives them to anyone he wishes” (Dan. 4:25), and should confess that God “does as he pleases with the powers of heaven and the peoples of the earth” (4:35). Empires and dynasties—to say nothing of one election—become much smaller when viewed from an eternal perspective.

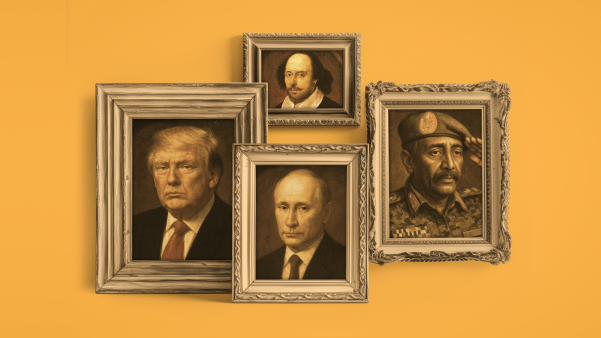

Focusing on the King

A number of biblical scholars have suggested that kingship is a “root metaphor” for the Bible’s depiction of God. If that’s anywhere close to a fair assessment, God’s kingship needs to become more of a root for our lives. If our perception of God as king is accompanied by wonder and awe at his greatness and glory, we learn to trust the author of our story, our nation’s story, and all stories. We realize that the great story that shapes our lives is not our particular vision for American democracy or freedom or prosperity, but the story of a global kingdom that will bring “the freedom and glory of the children of God” (Rom. 8:21).

When less potent metaphors dominate our view of our King, we’re susceptible to frayed nerves at the thought of the wrong president, the wrong judges, and the wrong laws. But we balance prayerful concern and inform our faithful presence with the certain knowledge that we will always have the right King, and we can get on with the business of loving and serving him and our neighbors, regardless of their political affiliation.

I sometimes hear that certain departed saints would “roll over in their graves” if they saw particular political outcomes: another Bush, another Clinton, or a reality TV star in the Oval Office. I’m not sure that’s accurate. Certainly, we see the martyrs in heaven looking down and longing for justice. But those who stand in the presence of the enthroned King of the universe have their tears wiped away. Far from rolling in graves, they’re dancing with praise. They invite us to share the peace of knowing that there is a King whose will is going to be accomplished, and whose kingdom is coming: As in heaven, so it will be on earth.

Seen from the throne room, Election Day and Inauguration Day are opportunities to remember the unelected King, regardless of whether they produce the outcome we desire. The only inauguration that ultimately matters occurred 2,000 years ago, when the Emperor of the cosmos showed up in the flesh to launch an Empire without end.

Jason Hood serves as director of advanced urban ministerial education and teaches New Testament at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary’s Boston campus. Parts of this essay are derived from his next book, God’s Empire, forthcoming from IVP.